WILMINGTON – Nearly 11 months to the day after news broke that Cape Fear Public Utility Authority could not remove GenX contamination in drinking water, its board will learn what staff considers to be the best option for filtering such fluorochemicals.

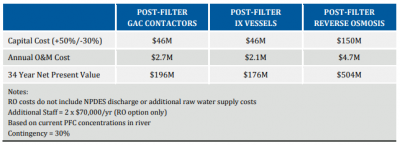

The recommendation, to be presented at CFPUA’s board meeting Wednesday, follows months of work with engineering firm Black & Veatch to gauge the efficacy of two filtering options. The utility released the firm’s report Wednesday. While some data analysis remains incomplete, granular activated carbon, or GAC, appears to be the utility’s likely choice over ion exchange, or IX. Both methods reduced concentrations of GenX and related substances. Neither could consistently remove all of them completely.

Supporter Spotlight

“It could be we need to do more study, but we think enough of the pieces to the puzzle will be in place (by the board meeting), said Jim Flechtner, CFPUA executive director. “We’ll have the cost estimates from Black & Veatch that says, ‘If you spend this much money on construction and this much every year in maintenance, here’s what you can expect in terms of removal.’”

The upgrades are estimated to cost about $50 million. If the board gives the go-ahead, construction would follow a one-year design process and take about two years. The project would increase ratepayers’ bimonthly bills by about 16 percent.

CFPUA hopes to recoup those and other GenX-related costs and damages, totaling $1.7 million so far, as part of a lawsuit filed against Chemours and DuPont, which formed Chemours in 2015. Both companies have operated the chemical plant at the Fayetteville Works, about 100 miles upriver from Wilmington, which is the source of GenX in the water.

“The lawsuit hasn’t been settled by any means,” Flechtner said. “In my opinion, it’s something that we shouldn’t have to be paying, but it’s the reality of our circumstance. It’s something that we do need to spend money on right now.

“There has to be a community dialogue. We represent all of our community. This is a decision we’ll all have to make,” he said. “Our job is to lay out all the information we have, explain what we know and what we don’t know and say, ‘Here’s what we can do, here’s what it will cost, and here’s the benefit we think the community would receive from it.’”

Supporter Spotlight

If the board decides to move forward, the utility would spend a year designing the upgrades and two more years constructing them.

CFPUA’s filter tests and water monitoring were funded in part by $185,000 allocated in N.C. House Bill 56. Last month, Flechtner presented a final report on CFPUA’s HB 56 work to House Select Committee on North Carolina River Quality.

Among other things, his report noted that GenX accounts for only a small percentage of the 30 fluorochemicals found in CFPUA’s water. And, he told the committee, much remains unknown: Analysis by researchers at the University of North Carolina Wilmington turned up five fluorochemicals never mentioned in scientific literature. Little to nothing is known about the health effects of most of the 30 substances, either singly or in combination. Fluorochemicals in general persist for many years, so how long contamination may remain in the river and water systems such as CFPUA’s remains unclear.

Some committee members reportedly questioned Flechtner’s objectivity, with Rep. Jimmy Dixon, R-Duplin, charging that Flechtner “made the problem look bigger than it really is.”

Flechtner responded that he was simply providing “perspective,” according to news reports.

For CFPUA, figuring out how to deal with emerging contaminants such as GenX involved pioneering tests on the effectiveness of GAC and IX.

In choosing between the two, CFPUA is considering more than just GenX removal. For example, fluorochemicals aren’t the only contaminants in the water, and GAC may be better at removing substances such as some pharmaceuticals and beauty aids.

“We view it (GAC) as a better defensive barrier than one (IX) that’s so specifically targeted to one compound,” Flechtner said. “Just from the broad look at it, GAC would make more sense.”

What about reverse osmosis, or RO? Some experts believe RO could be better at tackling GenX. GAC likely will work best with so-called “long-chain” fluorochemicals such as PFOA or C8, which GenX replaced. Its effectiveness may diminish for substances with fewer carbon atoms — “short-chain” fluorochemicals — such as GenX and similar substances in CFPUA’s water.

CFPUA initially considered RO but set it aside because of costs, waste-disposal challenges and other considerations.

Brunswick County, which also draws drinking water from the Cape Fear River, is looking at an RO system, but that may be driven by considerations beyond GenX.

For one thing, despite its inability to remove GenX, CFPUA’s Sweeney Water Treatment Plant, where murky Cape Fear River water is turned into something drinkable, is considered a state-of-the-art facility compared with plants such as Brunswick’s.

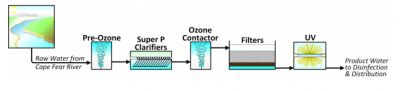

Sweeney’s technology includes ozonation, biofiltration and UV disinfection, features found at only a handful of water utilities in North Carolina. As a result, unlike Brunswick and many other utilities, CFPUA can remove most 1,4-dioxane, a likely carcinogen, from water it treats.

Utilities such as Brunswick and Fayetteville Public Works Commission have detected 1,4-dioxane in drinking water at levels exceeding the EPA’s health advisory for long-term consumption.

“I don’t see us going with reverse osmosis for several good reasons. We’ve already invested in good treatment at Sweeney, so we need to make good use of the investments we made,” Flechtner said.

“It takes a lot of water to use an RO system. We have the capacity to treat 44 million gallons a day. To treat 44 mgd with RO would exceed our allocation of raw water. We’re not at 44 million gallons a day, but we have to look to the future.”

Months spent monitoring the water and testing filtration options have focused CFPUA more intently on the challenges posed by emerging contaminants such as GenX tainting the Cape Fear River, source of almost four-fifths of the 17.4 million gallons sent to New Hanover County customers on an average day.

The work also thrust CFPUA into roles usually filled by regulatory agencies such as the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“We’re much more aware of emerging contaminants,” Flechtner said. “Our role as a utility is much different than EPA or DEQ. It’s their job to understand what chemicals are out there, whether they’re being discharged to the environment, what health impacts there might be and how that might affect drinking water. It’s our job to comply with the regulations and provide water that meets or exceeds those standards.

“In this case, something happened,” he said. “We have something in the river that we don’t know what the health effects are, and we can’t treat for it. Certainly, my perspective has changed about how the system works and whether it is effective and adequate. We’re doing this because no one else was.”

Lindsey Hallock, CFPUA’s director of public and environmental policy, said, “New Hanover is one of many utilities. Imagine how inefficient it would be if we decided this is the way we’re going to do things: Each utility is going to do its own testing and spend its own money and set its own standards and treatment goals.

“That can’t possibly be the solution,” Hallock said. “The solution is figuring out how to control these things at the source, figuring what are the appropriate levels that protect public health, protects the environment and protects people downstream while allowing businesses to operate. The only way that can happen is at the regulatory level.”