RODANTHE – Nathan Richards, head of the Marine Heritage Program at the University of North Carolina Coastal Studies Institute, is sitting next to an extraordinarily detailed drawing of the Pappy’s Lane shipwreck. Named after its location at the end of a street here, Richards and his team were recently able to eventually identify the origins of the ship, even to the date of manufacture.

The remains are not particularly old, nor was there some catastrophic moment associated with its sinking, yet the ship and the story it relates is, for Richards, a tangible piece of history that tells its own tale.

Supporter Spotlight

The journey to the Outer Banks and CSI began at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia. Richards was finishing his doctorate in 2002, concentrating in marine archaeology, and was one of the first marine archaeology doctorates the university awarded.

“My dissertation was on the phenomena of ship abandonment,” he said.

There was a job offer to work in Tasmania, based in Hobart, the largest city in the state. Before he accepted the position, though, another opportunity appeared.

“A job opened up at East Carolina University and all my professors there, and my adviser told me, in very strong terms, to apply,” he recalled.

At the time, ECU was one of the few colleges with degree program in marine archaeology. And although there has been an increase of the number of universities offering degrees in the field, according to Richards, ECU remains one of the leaders.

Supporter Spotlight

“There are very few universities that offer a program in marine archaeology, and even fewer, if any, offer the array of courses ECU has to offer,” he said.

ECU is the administrative campus for the Coastal Studies Institute in Wanchese. The institute was established in 2003 and includes member institutions Elizabeth City State University, North Carolina State University, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill and University of North Carolina Wilmington, as well as ECU. Richards began as head of the institute’s Maritime Heritage Program in January 2011.

The narrative that archaeology presents, Richards explained, sometimes confirms what we know about history; at other times it offers something new or different to what has been believed.

“Archaeology always has to play the role of an independent test,” Richards said. “That’s not to say a historian isn’t skeptical too. But an archaeologist has to think, ‘does the evidence fit the historical narrative?’ There are sometimes things we see in the archaeological record that may suggest that the historical record is slightly different or is wrong because people write the historical record from their point of view.”

Ships’ Graveyards

For Richards, that archaeological record lies beneath the waters of the world. The lost hulls and skeletons of ships are the constructs that tell the stories of communities and societies.

“For the majority of human history, as soon as human beings have been using watercraft, they don’t tend to wreck as often as they tend to be thrown away,” he said. “It is the idea that the abandonment phenomenon … corresponds to greater changes in culture, whether it’s technological or economic or social. A new technology comes in and a whole fleet of ships get abandoned.”

Richards noted that the circumstances leading to abandonment are remarkably similar across all cultures and through history. During the Great Depression, for example, there was a tremendous number of ships that no longer had economic value.

“You have a phenomenon like the Great Depression (when) a lot of ships need to be dumped at once because we don’t want them clogging up the harbors. So, they created designated places,” he said.

Those places are ships’ graveyards, and they are surprisingly common.

“Every major commercial harbor has a graveyard. Elizabeth City has a ships’ graveyard,” he said.

Even when abandoned or consigned to a graveyard, because of how ships are constructed, they continue to tell a tale.

“Ships are such investments and they are built so well … they’re difficult to deconstruct,” Richards explained. “Ships have always been reused for things. Whether it’s sunk as a foundation to a house … or used to create the shoreline of San Francisco, you look at how they reused ships that they didn’t need.”

Because ships are often the most visible remnants of a time and place, they can reveal unexpected information and those are the stories that Richards finds fascinating.

“I’m more interested in the anthropologically oriented archaeology. Which is to say the story is really interesting. It’s a story like a history,” he said.

The Outer Banks and coastal North Carolina, with its rich maritime history, is a continuing source of material, although Richards does not do as much field work as he had in the past.

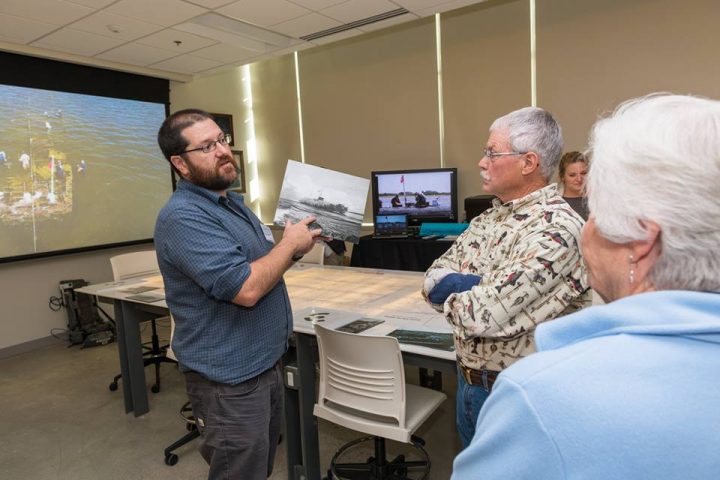

“I’m a program head here. I have a reduced teaching obligation in a formal sense. I have more of a role in having a public interaction. People from in the public come and ask for help on a project,” he said.

The public interaction, however, has led to some interesting studies for the students enrolled in the marine archaeology graduate program.

‘That (the public interaction) will often get fed to my students as a thesis idea. Their labor helps kill two birds, in a sense, helping a community and helping them get their thesis,” he said.

“My students’ (studies) are very broad. We have students working on very modern things, World War I, World War II and earlier stuff like the Civil War,” he added.

Those studies include a 2016 analysis of an attempt during World War II to create a protective arc of mines around Cape Hatteras for Allied shipping, resulting in three allied ships sinking with no report of any effect on German submarine, or U-boat, activity. A student also examined the Elizabeth City ships’ graveyard.

Currently there are several studies underway.

“We have lots of projects going on,” Richards said. “We’re finishing up Pappy’s Lane. I have a student working on Buffalo City (in mainland Dare County).”

The site, a logging company town from the 1870s until the 1950s that was once Dare County’s largest community, is now part of the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge.

“She’s looking at virtual recreation techniques to rebuild Buffalo City,” Richards said of the student. “Her idea is to use three-dimensional modeling to give people an idea of what that place looked like. I have a student doing a story on the dolphin fishery (at Hatteras Village). It’s not a pretty story to tell, but it’s an important one. I have a student doing a thesis on World War I off North Carolina. Another student I have is looking at the Chicamacomico Races (A Civil War incident on Hatteras Island). He’s seeing if he can determine the extent of that battlefield.”

The Outer Banks and coastal North Carolina seem to be the ideal setting for the work Richards finds interesting and important, and he addresses that idea in what he feels his students and studies can accomplish.

“I think,” he said. “This area is an excellent area for looking at the idea of maritime cultural landscapes and looking at how that has influenced people’s prosperity or economic growth and decline. That’s the great promise of a lot of this work.”

The Pappy’s Lane Wreck

Clearly visible from the shore, the Pappy’s Lane shipwreck isn’t the type of location that typically draws a lot of attention.

“It’s not the kind of site that anybody is going to go look for. You stumble upon it because you live here,” Richards said.

Yet a rusted, abandoned barge ultimately told a story steeped in history.

Located in the work zone for the proposed “jug handle” bridge that is to bypass the storm damage-prone “S-curves” of N.C. 12 north of Rodanthe, the North Carolina Department of Transportation needed to have the site researched.

Although the shipwreck was apparently recent, Richards and his team found conflicting stories about its origin.

“That whole part of the Pappy’s Lane story was that it was a barge, and there were all kinds of different stories and that there was something deeper, some other story or stories to get at,” Richards said.

What followed was a search for facts that sounded like the plot of a mystery novel.

The wreck first appeared on nautical charts in 1969.

“That doesn’t mean it first appeared in 1969, but it had to be there in 1969,” Richards said.

Visits to the Outer Banks History Center revealed photos taken over many years showing the wreck’s superstructure as it gradually deteriorated.

At first, Richards thought the wreck might have been a converted Coast Guard buoy tender or possibly one of the ocean barges used for the construction of the Panama Canal. A team of interns, however, spending their time in the shallow but cold waters of Pamlico Sound meticulously measuring the wreck, ruled out both possibilities.

The interns, however, did notice a very distinctive feature on the stern: skegs, or fins, that would have housed two propellers.

That was the key to the discovery.

The ship, as it turned out, was a type of World War II military craft capable of operating close to shore. But it wasn’t immediately clear whether it was an LCI, or Landing Craft Infantry, or an LCS, or Landing Craft Support.

LCIs could bring an entire company of infantrymen ashore. But because these vessels were only lightly armed, it quickly became apparent that sending men onto a beach required close artillery support. LCS’s used the same LCI design but were heavily armed, carrying more armament into battle than any other ship of their size.

Further research revealed that the Pappy’s Lane wreck was the LCS (L)(3)-123, launched in November 1944 and built in Neponset, Massachusetts, by George Lawley & Son, the creator of the LCI and LCS designs.

After serving throughout the Pacific, the ship was sold as surplus in 1947 to the Hunt Oil Co. of Hampton, Virginia, which converted it to a fuel barge.

The ship ran aground in 1969 during an unsuccessful attempt to refloat two gravel barges that were hauling stone for the construction of N.C. 12 on Hatteras Island. Refloating and salvaging the ship would have cost more than the value of the craft and it was abandoned, Richards explained.