“I don’t know if many people knew what was going on here during the war. It was a terrible time and it was a frightening time.” — Della Gaskill, 80, of Ocracoke

In December 1941, shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Adolph Hitler declared war on the United States. Not long afterward, German submarine Adm. Karl Doenitz put into action a plan to close off the transport of oil, lumber and other products crucial to U.S. military operations along the East Coast. The plan was called Paukenschlag, often translated as “Drumbeat” or “Drum Roll.”

Supporter Spotlight

Between six and eight German submarines, which Winston Churchill nicknamed U-boats, were sent to the coastal waters of the Atlantic Seaboard. Merchant ships traveling along shipping lanes from Maine to Texas were targeted, including those just east of the Outer Banks. In the first four months of 1942 at least 200 ships were destroyed. More than 60 were lost off the North Carolina coast, including at least 14 near Ocracoke and Cape Lookout. Only one U-boat was destroyed during this period when, on April 13, the USS Roper caught the U-85 on the surface and sank it.

Most of the attacks took place at night. The ships made easy targets. Unaware of the lurking submarines, they kept their lights on and radioed their whereabouts to each other and, inadvertently, to the Germans. Many towns and cities ignored blackout regulations and kept their lights on, providing the U-boats with excellent silhouettes of the target ships. So successful was the German plan in the first months of 1942 that it was referred to it by German captains as the “Atlantic Turkey Shoot.”

Most of this carnage was kept secret from the rest of the country, for fear of causing a panic. Not even the people living on the Outer Banks were informed, but they soon came to know of it. Often they saw the great fires where the ships were burning at sea. Even when ships were torpedoed too far out to be seen, flotsam, debris and sometimes bodies washed up on shore. Oil and oiled seabirds littered the beaches as well. Extra servicemen were stationed at the old and the new Coast Guard stations, and the Navy and Coast Guard patrolled the beaches, often riding big horses which they brought with them, or sometimes using island ponies.

The first attack on the Outer Banks came on the night of Jan. 18, 1942, 60 miles off Cape Hatteras. Two torpedoes ripped apart the tanker Allen Jackson, spewing 73,000 tons of oil into the ocean and immediately catching fire. Of the 35 crewmen on board, only 13 survived. They were rescued the next morning by the destroyer U.S.S. Roe. Two more ships were struck that day off Cape Hatteras.

Sailors who were rescued over the next months were housed on the sound side of Ocracoke’s new Coast Guard station in tar-papered barracks until they could be transferred to the mainland.

Supporter Spotlight

Many of the island men were away in early 1942, working on Army Corps of Engineers dredges in Philadelphia, Boston and Norfolk, or on Merchant Marine ships. Some returned home and enlisted or were drafted to fight.

By the end of January 1942, about 12 ships had been destroyed along the Outer Banks, and the month of March alone saw 25 losses. One of these was the freighter Caribsea. Its second mate was a man from Ocracoke, Jim Baum Gaskill, whose parents, Bill and Annie Gaskill, ran the Pamlico Inn.

Jim Baum Gaskill was 25 when he entered the Merchant Marines and joined the crew of the Caribsea. The ship was torpedoed as it passed near Cape Lookout, and Gaskill was killed. His framed license drifted up on the beach at Ocracoke and was found by his cousin Chris Gaskill. The ship’s nameplate, still attached to a board from the ship, floated into the Pamlico Sound to the dock of the Pamlico Inn. The piece of wood bearing the nameplate was later used to build a cross, which now stands at the Ocracoke United Methodist Church.

Another Ocracoke resident whose ship was torpedoed in Ocracoke waters was Art Bryant. He was a member of the only black family living on the island. Bryant had joined the Merchant Marines when the war started, and he was on the ship Chilore on July 15 when it was torpedoed near Ocracoke and accidentally detonated a U.S.-placed mine. Bryant and the other survivors were brought ashore and he was able to visit with his family.

The Navy realized they needed help in patrolling the Atlantic coast’s shipping lanes, so they asked the British Royal Navy for additional ships. The British sent 24 antisubmarine trawlers along with their crews. One of these, the H.M.S. Bedfordshire, was stationed in North Carolina.

On May 11, while sailing off Cape Lookout, the Bedfordshire was torpedoed by the German U-boat U-558 and sank, leaving no survivors. Three days later, two of the crew, Sub-Lieutenant Thomas Cunningham and telegraphist Stanley Craig, were pulled out of the surf by Coast Guardsmen at Ocracoke. Two more unidentified sailors washed up a week later. All were buried on a small piece of land donated by the Williams family. There has been an annual memorial service at what is known as the British Cemetery ever since.

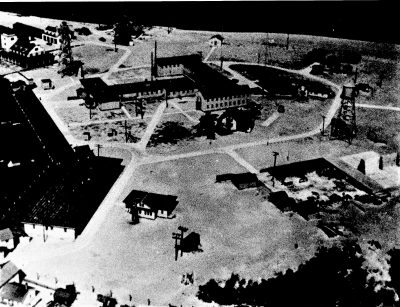

In response to the attacks, the Navy began in June 1942 construction of the Ocracoke Section Navy Base. This included dredging out the shallow village harbor, known as the Creek and now as Silver Lake, so that the Navy’s patrol boats could be anchored there. The material they dredged out had to be deposited somewhere, and three spoils areas chosen changed the island’s ecosystem.

The Navy built the island’s first paved road, leading from the base through the village to an area near what is now Jackson Dunes and Oyster Creek. Here, on a 47-acre plot, the Navy stored ammunition. The road was informally known as Ammunition Dump Road.

They also operated a radar and sonar tower at Loop Shack Hill, a series of sand dunes just outside of the village, with jamming equipment, radio high-frequency direction finding gear and new listening capacities.

Floating mines and anti-submarine nets were set out in Ocracoke’s offshore waters to protect the base and its ships.

As the early months of 1942 passed, the captains of the merchant ships sailing up and down the coast became more savvy, traveling together, and the U.S. Atlantic Fleet began providing escorts and set up a convoy system to protect them.

As a result, the number of casualties declined and by the time the base was completed in October, most of the attacks had ceased. The base nonetheless began operating, doubling the size of the island’s population so that, according to Della Gaskill, “it was like a little city within Ocracoke.” There were three power plants, a commissary, hospital, officers club and barracks.

In January 1944, the Ocracoke Section Base was converted to an amphibious training base, its purpose being “training personnel in the use of new secret equipment.” These personnel, who came to be known as “Beach Jumpers,” were trained to set up mock or dummy invasions, using such tactics as setting off firecrackers and smoke pots to simulate battle. After their training they were sent to battlefronts of the Pacific. The Beach Jumpers were active from 1943 to 1946 and again from 1951 to 1972. A monument, unveiled on Oct. 23, 2009, near Loop Shack Hill, commemorates these men.

After the amphibious training operations ended in 1945, the Navy base at Ocracoke was used as a combat information center until the end of the war, when it was torn down. The extent of the U-boat attacks, the radar and sonar operations at Loop Shack Hill, and the training of the Beach Jumpers remained classified for years after. Even the existence of the Navy base itself was kept secret from most Americans until the 1990s, and there are only a few remains today to suggest that it ever existed.

An exhibit at the Ocracoke Preservation Museum commemorates the World War II activities which took place at and around Ocracoke.