Against a backdrop of mutual challenges in the Albemarle-Pamlico estuary from climate change and budget shortfalls, an updated partnership between Virginia and North Carolina is starting to flex its collaborative muscle with important border-blind issues: wetlands, algal blooms and fish travel.

The memorandum of understanding, or MOU, that was signed Nov. 1 by representatives of environmental agencies in both states will make it easier for sharing of information and resources in management of the second largest estuary in the continental United States.

Supporter Spotlight

“This provides authorization for us to work cooperatively with our governmental counterparts across state lines,” said Bill Crowell, director of the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership, the federal-state program that facilitated development of the agreement. “It’s going to benefit all of us.”

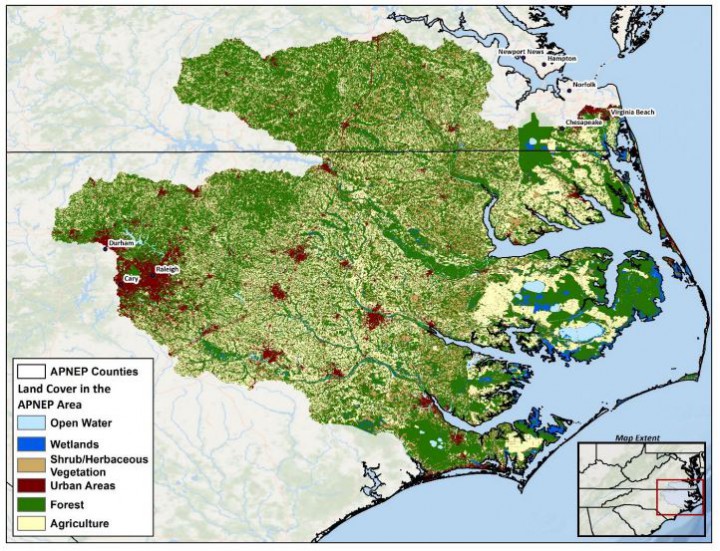

The program, founded in 1987, encompasses the Neuse, Tar-Pamlico, Pasquotank, Chowan, lower Roanoke and portions of the White Oak river basins, a total of 3,000 square miles of open water. Water from 43 counties in North Carolina and 38 counties and cities in Virginia drain into the 31,500 square miles of total watershed area.

Crowell said that previous attempts to update a similar MOU from 2001 were thwarted by the states’ changing politics and agencies. But in light of new administrations in Virginia and North Carolina, he said, it was decided last spring to give an update another shot.

“One of the points of that,” he said, “is to make it consistent with governmental structures so that everybody knows their role.”

A significant difference in the current MOU is that it is more focused, and it requires staff to follow-up on progress with an annual review, said Kirk Havens, chair of the partnership’s leadership council.

Supporter Spotlight

“I think that’s a really important part of it,” said Havens, the assistant director of the Coastal Watersheds Program at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. “It actually designates personnel to be part of the evaluation of the implementation.”

One of the first projects launched under the new agreement, he said, is a comprehensive combined wetlands inventory for the two states’ watersheds. Working off of existing GIS (geographic information system) maps from the National Wetlands Inventory, new maps will be created that show the totality of each wetland, irrespective of the state borders. Pertinent data on details such as submerged aquatic vegetation or invasive species could also be layered on the maps

“You look at them from the North Carolina side, and the Virginia side but we want to look at them from a watershed component combining GIS in a complement that’s shared,” Havens said.

Havens said he expects the new maps will be ready to be utilized by APNEP’s Wetlands Resource Monitoring and Assessment Team in a few months.

Considering that air and water, not to mention animals and plants, pay no attention to boundary lines, the partnership sees a lot to be gained overall in having a more holistic management option in the vast estuary.

For instance, in the Chowan River basin alone, it has been plagued in recent years by invasive hydrilla, an aquatic weed; blue catfish, a voracious non-native fish; and algal bloom, potentially toxic overgrowth of algae – all that threaten waters in both states.

The bi-state approach fostered by the new agreement is not reinventing the wheel, but instead is incorporating existing data sets and planning strategies, Crowell said. Now they can be more readily shared and coordinated. A lot of the communication will be done electronically, although there will also be meetings held in different locations throughout Virginia and North Carolina.

It won’t equal the star power of the Chesapeake Bay multi-state consortium, but it may help the Albemarle-Pamlico to gain more of the attention from the Chesapeake – the largest estuary.

Funding is not provided in the MOU, Crowell said, but the agreement can make is easier for states to co-apply for grants and share costs of a project.

Increasing impacts from sea level rise and climate change have exacerbated the ongoing stresses to the ecosystems. Still, saltwater intrusion, flooding, erosion and loss of habitat, among other related issues, have been on environmental management radar screens in the region for many years.

“That just adds to the problem rather than being a separate problem,” Crowell said of climate change.

Efforts have already been coordinated between state environmental agencies to coordinate data sharing in the Chowan and Pasquotank river basins.

On the North Carolina side of the Chowan basin, algal blooms that have persisted for several years are still not understood, and the partnership is hopeful that agreement will help both states to work to identify the cause.

“We’ve been doing cross-border things for years,” Crowell said. “Most of what we do is supportive of our partners mission.”

Other projects the partnership plans to tackle in coming months include work to address fish passage and spawning habitat issues, nutrient pollution from drainage and invasive aquatic grasses and fish. The agreement is also expected to improve communication and coordination with the Roanoke Bi-State Commission.

“I think it’s timely and we want it to be something that’s meaningful and shows consistent results,” Havens said. “A lot of this is trying to improve the quality of life and natural resources for those citizens living by those waterways.”

The agreement also expands the access to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which is Region 4 in North Carolina and Region 3 in Virginia, and expands contacts with non-governmental groups in both states.

“At the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership, we see if we’re having better relationships with our northern neighbor, then that can only help us fulfill our mission with all our partners,” Crowell said. “It’s important that we actually do something under this MOU. I think we’ve started getting the conversations going.”