NAVASSA — The extent of creosote contamination in the soil and groundwater on and around a former wood treatment plant is of “various levels,” according to a remedial investigation of the site.

“The most heavily impacted area is what we call the process plant and the ponds,” explained Richard Elliott, the Multistate Environmental Response Trust project manager of the federally designated Superfund site in Brunswick County’s Navassa.

Supporter Spotlight

Logs coated in creosote, a gummy, tar-like mix of hundreds of chemicals used as a wood preservative, were stacked and dried before being loaded onto trains.

The top 3 or 4 feet of soil in the area in which the logs were placed to dry has higher concentrations of contamination, but that soil can likely easily be removed and replaced with contaminant-free dirt.

Samples routinely taken from 69 monitoring wells drilled in and around the site reveal creosote has traveled anywhere from 10 feet below the surface to a depth of as much as 90 feet below the surface and it is affecting the groundwater, Elliott said.

“Creosote is heavier than water, so it’s going down,” he said. “It’s dense, so it’s tending to just flow down.”

The plume of contamination in the groundwater is slow moving, staying relatively in the same area since the Kerr-McGee Chemical Corp. treatment plant closed more than 40 years ago.

Supporter Spotlight

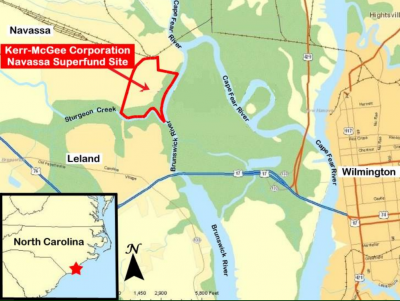

The facility included 245 acres of upland and marsh and was in operation under various companies from 1936 through 1974.

The site was added to the National Priorities List of federal Superfund sites in 2010 because of the contamination in groundwater, soil and sediment.

The overall goal is to contain, clean up and restore the land so that it may be re-used for the benefit of the small Brunswick County town, which is bordered by Sturgeon Creek and Brunswick River.

Officials with the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, the Multistate Trust and North Carolina have been holding quarterly meetings to update Navassa residents about the ongoing investigation into how the contamination is affecting the environment and health of those who live in the community.

During the most recent quarterly meeting held Tuesday in the town’s community center, residents asked an array of questions, including whether some of the animals they eat – fish and deer, for example – are being tested for contamination.

The answer: Officials have not investigated any potential long-term health effects from eating fish and wild game taken from the area.

Dave Mattison, Superfund Section project manager with the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, or DEQ, said samples collected between 2008 and 2009 of bugs in the marsh revealed that the bugs present were not affected by contamination.

“You saw an absence of critters,” he said, meaning those that were affected were no longer in the marsh.

“Most of that marsh is in fairly good shape,” Mattison said.

Over time, Elliott explained, Mother Nature has taken control of the effect contamination has had on the marsh, which is roughly 90 acres.

Within the marsh, an area of about 1 to 3 acres may pose a risk to so-called ecological receptors, which include any living organisms other than humans, officials said.

“The next phase is what to do about it,” Elliott said. “It’s a tricky thing on how you clean up a marsh. The problem is, the more you get into it the more problems you cause.”

For that reason, officials may focus initially on 1 acre and see how remediating that acre goes before branching out to a wider area.

site into the marsh and uplands. Photo: NOAA

Elliott said that about 50 to 70 acres of the roughly 153 acres of uplands on the site could be relatively easy to clean for re-use.

Those areas include drainage swales on the property and the top few feet of contaminated soil.

“The likely answer is we’ll just excavate that stuff and put in clean dirt because it’s limited, localized and we can do it quickly,” Elliott said. “You could probably get that clean enough for some type of commercial or even residential use.”

In the areas where creosote has been found as deep as 90 feet below the surface, including where it was processed and placed in unlined ponds, clean up will be more complicated.

These areas may be reserved for industrial use with restrictions, including the depth at which someone can dig on the land, Elliott said.

He encouraged residents to use their imaginations and offer input on how the land may be re-used.

“Don’t let this stuff inhibit your creativity on how you want this site to be used,” Elliott said. “It’s our intent and our charter to do something there that the community agrees with. The community doesn’t have a say in who buys that land directly. On that part of it you’re going to have to believe that we’re going to do the right thing.”

The town does have a say in how to zone the land, which will guide future use of the property.

The site is currently zoned heavy industrial.

A community development workshop is being hosted Feb. 22-24, during which time residents will be asked to give their input on how the land should be re-used.

The EPA is expected to publish in 2019 a record of decision documenting the cleanup plan and detailing how the land may be used.