Editor’s Note: Coastal Review Online is now featuring the work of North Carolina historian David Cecelski. Cecelski writes about the history, culture and politics of the North Carolina coast. Cecelski shares on his website essays and lectures he has written about the state’s coast as well as brings readers along on his search for the lost stories of our coastal past in the museums, libraries and archives he visits in the U.S. and across the globe.

When I was using the British Newspaper Archive (BNA), I also did several general searches to see how the British press covered my home state of North Carolina in the 18th and 19th centuries. I was interested in what the British public saw when they looked across the Atlantic at us.

Supporter Spotlight

The BNA is gradually putting online the vast holdings of the British Library’s newspaper collection, which reaches across more than three centuries and includes more than 60 million newspapers.

Not surprisingly, I found many newspaper articles on the wars with England, the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, and even more stories on the American Civil War.

I also discovered quite a few articles on Scottish emigration, shipwrecks and slave conspiracies.

But I discovered that, when the British looked toward North Carolina’s shores, they saw one thing above all: turpentine.

Turpentine, Tar & Rosin

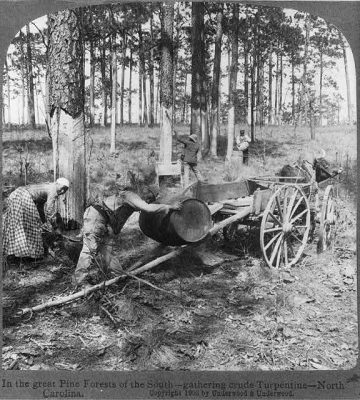

For much of the 18th and 19th centuries, North Carolina’s longleaf pine forests supplied Great Britain and much of the rest of the world with turpentine.

Supporter Spotlight

Carolinians — including untold thousands of slave laborers — harvested and distilled raw turpentine from longleaf pine trees into “spirits of turpentine” and rosin, which was a byproduct of turpentine distilling.

In addition, they produced tar by burning longleaf pine wood in earthen kilns.

Merchants and manufacturers referred to spirits of turpentine, rosin and tar as “naval stores.” All drawn from the resin of longleaf pine trees, they played indispensable roles in rendering the wooden hulls of sailing ships watertight and in preserving their hemp rigging — hence their name, “naval stores.”

The navies and merchant fleets of the world could not have stayed at sea without them.

Spirits of turpentine, tar and rosin had scores of other uses as well. In the case of spirits of turpentine, those uses ranged from being a popular illuminant to serving as a key ingredient in paints, varnishes and many solvents.

I first wrote about the naval stores industry in eastern North Carolina 20 years ago in an historical essay titled, “Oldest Living Confederate Chaplain Tells All? Or, James B. Averitt and the Rise and Fall of the Richlands.” That essay focused on a plantation called the Richlands, in Onslow County.

I tend to look closely at small worlds, like that of the Averitt family, the 120 slaves and the 20,000-acre “turpentine orchard” at the Richlands, and see what close study might reveal about American history.

The British press took the opposite tack: the BNA’s newspapers were interested in the big view — in world markets, import prices and the availability of North Carolina’s naval stores for use by British vessels and manufacturers.

The Carolinas Furnished the World

The earliest reference to North Carolina’s naval stores industry that I found in the BNA was in the shipping news for the May 3, 1714, issue of the Stamford Mercury in Stamfordshire, England.

From then on, I routinely found references to the colony’s — and later, the state’ s — naval stores industry in the shipping news of Liverpool, London and other ports.

I also frequently found references to North Carolina’s naval stores in two other parts of British newspapers.

First, I found them in monthly and annual reviews of the country’s leading commodity prices.

Second, I found them in a long string of articles by British travelers who visited North Carolina and sent news reports back home.

The British newspapers’ association of North Carolina with turpentine and other naval stores is unmistakable. As the Derry Journal, on 25 Sept. 1861, noted, “Of turpentine and naval stores the fine forests of the Carolinas furnished the world with its chief supply.”

American imports crowded British seaports: sugar, rum and molasses from the West Indies, rice and indigo from South Carolina, tobacco from Virginia, cotton from much of the South, mahogany and other precious woods from Central America, and many others.

In 1855, though, a widely republished article about the nicknames of the states in the U.S. makes clear what North Carolina was most famous for: North Carolina was “the Turpentine State.”

From Turpentine to ‘Rock Oil’

One of the most interesting things that I read in the British press about North Carolina and the naval stores industry concerned the impact of the American Civil War on world markets.

In the first days of the Civil War, a business column in the Cork Examiner, in the Republic of Ireland, noted, “the supplies of spirits of turpentine from North Carolina had nearly ceased.”

Almost overnight the Union navy’s blockade of Confederate shipping had extinguished the American trade in turpentine, tar and rosin.

The wartime shortages caused an upheaval in the global naval stores industry.

I could see that revolution in an annual review of the naval stores market that was published in the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, a London paper, on Jan. 26, 1863.

The article begins:

“Perhaps the first thing that strikes the mind in glancing over the figures of receipts, etc., for the past year, … is a feeling of surprise at the magnitude of the difference between the year just closed, and all previous time.”

A year earlier, the turpentine markets had been in crisis. With the outbreak of the American Civil War, the most important source of the British supply of naval stores had vanished.

What astonished the report’s author, however, was that, in only a year’s time, many British manufacturers and tradesmen had found alternatives to turpentine.

Spurred by shortages of American naval stores, they had turned to a newly discovered source of illumination, preservation and lubrication.

The Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser referred to the new alternative as “rock oil.” We know it as petroleum.

Light and Beauty

I have written elsewhere about petroleum’s role in the decline of the whale oil industry in the 19th century — that was in an article on the William F. Nye Co.’s dolphin oil factory on Hatteras Island, N.C.

I had not realized that the discovery of petroleum had also turned upside down the turpentine industry.

“Instead of camphene and the kindred articles, formerly used for illuminating purposes, made chiefly from spirit turpentine, the world, literally, is using petroleum … ” The Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser reported.

Other replacements for turpentine also grew in popularity. Varnish markers, for instance, began using naphtha, a petroleum distillate, instead of spirits of turpentine.

“The whole matter,” the report concluded, “seems like a providential provision to supply the country and the world with light and beauty, the ordinary sources of which had been cut off by the rebellion of the South.”

The market report went on to say that a few small shipments of turpentine had arrived in Liverpool from New Bern and Beaufort, North Carolina, after their capture by Federal forces in early 1862. But the analyst also indicated that those shipments combined did not equal what had routinely arrived in British ports aboard a single packet from Wilmington, North Carolina, before the war.

All is Turpentine Country

The Civil War did not finish off North Carolina’s naval stores industry, though, as the longleaf pine forests declined from over-exploitation, the center of the industry continued to shift south and west.

As every genealogist here knows, you can trace a long trail of families from southeastern North Carolina’s piney woods to less exploited longleaf forestlands in South Carolina, Georgia, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and East Texas.

But that great upheaval unfolded over generations. Immediately after the Civil War, judging from the British press, you could still find plenty of eastern North Carolina communities where the naval stores industry, even in decline, was still a way of life.

On June 7, 1866, for instance, a correspondent for the Man of Ross, and General Advertiser, in Herefordshire, England, wrote about his recent visit to the Lower Cape Fear.

He called Wilmington “an uninviting dirty town … ” but one “doing a large business.” It is, he wrote, “the greatest turpentine and rosin depot in the country.”

As the English correspondent traveled the railroad from Goldsboro to Wilmington, then south toward Charleston, S.C., he wrote, “all is turpentine country.”

He wrote: “At every station we stopped … I saw vast numbers of barrels of turpentine and rosin. … In fact, each station or village seemed to consist of only a few unpainted houses and a turpentine stall.”