CHAPEL HILL — After this summer’s revelations about the extent of GenX and other compounds in the Wilmington region’s drinking water supply, state and local officials have vowed to do two things: Secure the safety of the water and prevent similar events from occurring in the future.

As testing and cost estimates of additional filtering and treatment come in, the first goal is looking possible, but expensive. The second goal, however, appears for now to be far more elusive.

Supporter Spotlight

Although the state now has two legislative committees, a newly reformed science panel and resources in two state departments committed to effort, there’s no consensus yet on a way forward when it comes to identifying what unknown contaminants are in the state’s drinking water sources, how to regulate them and how all that is communicated to the public.

“Issues around emerging contaminants have been known problematic issues for a long time and yet no one that I’m aware of has come up with a full map for getting on top of their presence in the waters that we use,” said Richard Whisnant, professor of public law at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill’s School of Government and a newly appointed member of the state’s Environmental Management Commission. “It’s one of those things that we as a state are going to have to take one bite of at a time.”

Challenge of the Unknown

Whisnant said that with a rapidly expanding universe of compounds, a major part of the challenge is knowing what to look for and then knowing what to do with the data once you have it, he said.

Then, there is the challenge of resources.

Regulators and public health officials are going to have to develop a kind of triage system, Whisnant explained, one that prioritizes contaminants that are of the highest concern.

Supporter Spotlight

“I think a next-level question is, ‘Are there ways of grouping this huge world of emerging contaminants into things that deserve special scrutiny either on the monitoring and permitting side or on the back-end testing health effects side?’” he said.

Robin Smith, a consultant who served as assistant secretary of the Department of Environment, Heath and Natural Resources, now the Department of Environmental Quality, said she agrees that prioritizing the emerging contaminants is a key step.

“One of the challenges is that there are so many chemicals out there,” she said. “So, to wrap your arms around it, you have to have some way to at least start figuring out what you’re most concerned about and how to address those that are of highest concern.”

But Smith said the state doesn’t have to wait to develop a new regulatory program to start tightening oversight and permitting. It could use existing programs to take action on emerging contaminants that are not yet regulated under federal rules.

“There’s certainly some authority at the state level to go beyond where federal rules are,” Smith said.

The state could adopt drinking water standards for chemicals for which the Environmental Protection Agency has no national adopted standards, she said, and the state can also adopt a stricter standard for those that do have a federal standard. DEQ regulators could also apply more scrutiny in issuing discharge permits.

Any new oversight will take a serious commitment to the science behind it, she said.

“To make that possible it’s important to have the expertise at the state level to do the kind of risk analysis that’s necessary.”

At the minimum, that’s likely to mean adding at least another state toxicologist at the Department of Health and Human Services and additional science positions at DEQ to make up the core of a new program, she said.

Industry Pushback

If the state does move ahead on regulating emerging contaminants, any proposal is likely to face heavy scrutiny from manufacturers.

Preston Howard, president of the North Carolina Manufacturer’s Alliance, was contacted but declined to comment for this story. Howard said that, for now, the organization is not prepared to comment on potential legislation or regulatory proposals. But during a recent forum on environmental issues at Meredith College in Raleigh, Howard said the organization is watching the GenX response and will seek to have input into any regulation that results.

Whisnant said there is no doubt there would be strong pushback from manufacturers and other discharge permittees if they determine the state has gone too far.

One friction point is whether a new chemical may be discharged without extensive testing of its effects on human health. Advocates, including some Republicans in the legislature, say a regulatory system that uses a precautionary principle to vet new chemicals and compounds could be the safest approach.

“If there are emerging compounds that are discharged into our water and we don’t know what they do, then they do not need to be discharged in our water,” New Hanover Republican Rep. Holly Grange, co-chair of the new House Select Committee on North Carolina River Quality, said in a meeting last week. “That’s really what the bottom line is here – to make sure we have safe drinking water for all the citizens across our state.”

But the change would require a major regulatory overhaul from a legislative leadership that has overseen extensive regulatory rollbacks.

Whisnant said that while there is some support now for a precautionary system, it’s hard to imagine the more stringent so-called “European model” making it through the North Carolina General Assembly.

“I don’t think it’s tenable at that level,” he said. “I think we’re going to have to evolve to something like, ‘What’s the set of things we won’t put in the river unless we know it’s safe?”

Legislation Coming

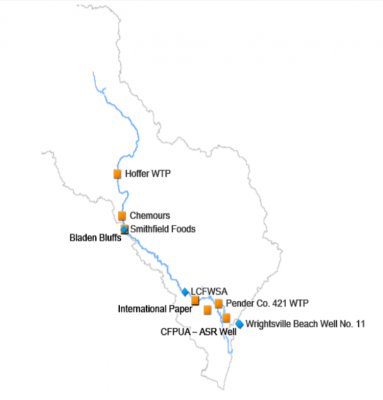

One clear area of agreement is that the issue of emerging contaminants has expanded beyond GenX and the lower Cape Fear River basin.

Last week during the second meeting of the House Select Committee on North Carolina River Quality, chair Rep. Ted Davis, R-New Hanover, said he expected the next round of legislation to be a statewide approach.

Last month, the legislature passed legislation sending $435,000 in state money to the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority for new filtration systems and the University of North Carolina Wilmington for testing to determine the extent of contamination in the lower Cape Fear.

Davis said he expected the committee’s fact-finding phase to wrap up this month and then will begin working on legislation. He noted that the timetable is tight since next year’s short session of the legislature could start as early as March.

In a presentation to the committee last week, Detlef Knappe, an environmental engineering professor at North Carolina State University who was part of the team that published the Cape Fear study on GenX, underlined the need to expand the scope of a response statewide.

Knappe told the committee there are areas of concern farther up in the Cape Fear watershed, where testing shows high levels of bromide and 1,4-Dioxane and PFASs, or per- and poly-fluroalkyl substances. He also noted ongoing studies that show levels of 1,4-Dioxane far above the surface water standard in long stretches of the Haw, Deep and Cape Fear rivers.

Compounding the problem, he told committee members, is that the contaminants are not being filtered out by standard wastewater treatment plants and are being returned to the river.

Knappe said that in addition to better oversight of wastewater permitting and reducing discharges, the state needs to invest in treatment systems that deal with emerging contaminants.