The Lost Colony of Roanoke Island has gotten all the press, but it was not the only failed attempt to tame the Outer Banks by the English.

Colington Island is perhaps one quarter the size of Roanoke Island. Bordered to the south by Kitty Hawk Bay and to the north by Albemarle and Roanoke sounds, it lies due west of the Wright Brothers National Memorial.

Supporter Spotlight

The island is almost entirely residential; there is one combination gas station and convenience store, a pizza restaurant and Billie’s Seafood just over the bridge at the beginning of the island. Colington Road is a narrow, twisting two-lane affair, a reminder that at one time roads meandered around natural barriers and property lines.

It is named for Sir John Colleton, Baronet of England, who was first to claim ownership of the island and one of the eight Lords Proprietors who were granted almost all of the lands south of Virginia by Charles II.

Throughout the mid-17th century, Britain was engulfed in a horrific civil war. Although Oliver Cromwell and his Parliamentarians soundly defeated royal forces at every turn, after Cromwell’s death in 1658, Parliament, politically paralyzed with no effective leadership, invited King Charles II to resume the monarchy.

During the civil war, a number of prominent British subjects had provided substantial aid to the crown, among them Sir John Colleton.

“He was a royalist officer, spent a fortune raising troops (and) was a refugee to Barbados …” historian Lindley Butler explains.

Supporter Spotlight

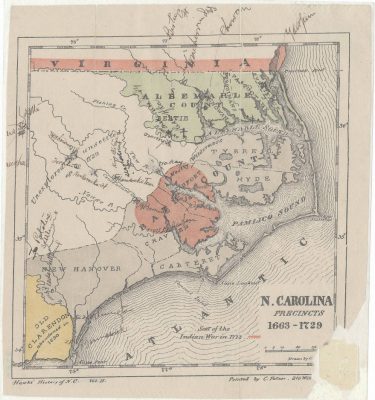

The reward for that support was huge. In 1663, Charles II rewarded eight of his most trusted supporters, including “… our right trusty and well-beloved Sir John Colleton, Knight and Baronet …” land grants of everything south of Virginia.

The eight supporters have become known as the Lords Proprietors.

On Sept. 8, 1663, Sir Colleton, living in Barbados on a working plantation, was given “… which Island hath been called by some Cariyle Island, but now by us named Colleton Island.”

After receiving his royal grant, Colleton moved quickly to develop his new holding, appointing Capt. John Whittie as his agent.

Whittie, acting on Colleton’s behalf, purchased cattle, horses and hogs, sailed to the Outer Banks, entering Roanoke Sound through the now closed Roanoke Inlet. The plan was to clear the land, plant corn and tobacco as cash crops and raise livestock. A vineyard was also started — probably from native muscadine grapes — with the hope of starting a winery.

Whittie and the workers he brought with him set to work, planting crops, constructing a 20-foot home for themselves and as well as a 10-foot hog house. No records specific to Whittie’s time on “Colleton Island” have been found, but it seems that his efforts resulted in failure.

In 1665 Lord Colleton turned to Peter Carteret to salvage the project.

The fourth cousin of Sir John Carteret, one of the Lords Proprietors, Peter Carteret was young, energetic and well-connected. Born in 1641, at the time he took over management of the Colleton Island Plantation, he was already an assistant to the Gov. Samuel Stevens of Albemarle County — the nascent North Carolina — and a lieutenant colonel in the colony’s militia.

From letters that Colleton wrote to Carteret, it’s clear the North Carolina venture was failing and there was little faith in Whittie. In September of 1665, Colleton wrote:

“I perceive you find our business in a very bad condition, for which I am in a great measure to blame. Capt. Whittie, who made us pay for 100 breeding sows, with pigs, 10 boars, 10 cows with calf and a bull, and a horse and a mare … Which it seems never came there, besides which we paid to the overseer’s friend here, who hath played the knave, and suffered all our business to go to wrack …”

A November letter from Whittie to Carteret confirmed much of Colleton’s sentiment.

“I hope the Country is pleasing to you though all things was not in order at Colleton Island according to your Expectation and merit. If God bless me well to that country I will call those persons to account that I left entrusted. I have been sufficiently played the knave …”

When Carteret arrived in the winter of 1665 his observations confirmed Colleton’s fears. “We arrived in Albemarle the 23d of February … and went to Colleton Island according to Instructions where I found a 20 foot dwelling house a 10 foot hog house and … wild hogs but Nothing towards a plantation so that I was to make a plantation out of the wilderness we cleared what ground we could …”

His further notes on the year were a hint of what was to follow.

“Corn … produced little by reason that we were all Sick all the Summer that we could not tend it and the Servants so weak the fall and Spring that they could do little work.”

Carteret did, however, begin improving the holding. He built an 80-foot dwelling to house himself and the workers; the hog house was expanded to 20 feet and the hogs rounded up. Corn was planted the following year and the rendering of oil from beached whales proved profitable.

Nonetheless, the Colleton Plantation continued to operate at a loss. In August of 1667 he reported, “… (there) happened a great storm or rather hurricane that destroyed both corn and tobacco: blew down the roof of the great hog house that I had built the year before carried away the frame & boards of two houses …”

The following year a July drought was followed by so much rain in August the crop was destroyed. There were more hurricanes and crop failures and by 1674 Carteret acknowledged the project was a failure, writing, “… that it hath pleased God of his providence to Inflict Such a General calamity upon the inhabitants of these countries that for Several years they have Not Enjoyed the fruits of their Labors.”

There is a twist to this tale, though. When the serving governor of Albemarle County, Samuel Stevens, died in 1670, the Council appointed Carteret to the post.

Carteret inherited a poverty stricken land, on the verge of famine after years of failed crops. Politically there was widespread discontent with decisions made by the Lords Proprietors that would eventually lead to the 1677 Culpeper’s Revolution.

After his appointment, Carteret’s notes on Colleton Island become much shorter, suggesting that he was not able to spend the time on site that he had before. In 1672, at the request of the Albemarle Council, he went to London to discuss directly with the Lords Proprietors and the Crown the concerns of the Albemarle settlers.

The trip was a failure and there is no record of Peter Carteret ever returning to Albemarle County.

As a further footnote, Carteret spent 350 pounds of his own money supporting the Colleton Plantation. Even with the help of an attorney, the Lords Proprietors never did pay him back.