BOLIVIA – A new set of recommended rules governing solar farms in Brunswick County would cap the size of solar panel fields and tighten setbacks around them.

Revisions to the county’s Unified Development Ordinance, or UDO, were unanimously approved Oct. 9 by the Brunswick County Planning Board.

Supporter Spotlight

The changes the planning board is recommending to the Brunswick County Board of Commissioners also include a requirement that solar energy farm operators submit to the county an updated decommissioning plan every three years.

The county currently requires a decommissioning plan for solar farm properties that are transferred from one owner to another.

A decommissioning plan details how equipment will be removed from a site once it is no longer in operation, how the property will be restored and a financial guarantee ensuring the responsible party can cover the costs associated with equipment removal and property restoration.

The new rules will not go into effect unless adopted by county commissioners, who are likely to hear from those in the solar energy industry who spoke out last week against the proposed changes to the planning board.

Commissioners initiated the discussion about revamping the county’s UDO solar farm requirements, including limiting the size of solar fields.

Supporter Spotlight

“There has been increased activity in this area,” said Brunswick County Planning Director Mike Hargett. “The commissioners have a general concern about the size of these sites.”

In response to that concern, the planning board voted to limit solar farms to no more than 50 acres, enough land to accommodate solar farms up to 45 acres and the required setbacks.

That recommended cap is 15 acres more than the 35-acre limit proposed by county planning staff.

The revisions approved by the planning board include the following setback requirements:

- 200 feet from thoroughfare roads.

- 100 feet from residential districts or residential uses.

- 100 feet from institutional uses.

- 50 feet from commercial districts or uses.

- 25 feet from industrial districts.

- A minimum of 500 feet from scenic byways.

Under the planning board’s recommendations, the UDO is reworded to urge solar farm developers to minimize grading and tree removal from a site. The proposed wording also strongly encourages developers to use native, low-growing grasses and flowers either before or after panel installation, and avoid completely cutting off wildlife corridors.

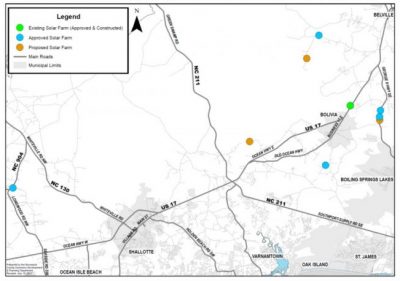

To date, nine solar farms have been approved for construction and operation in the county. Six farms approved in 2015 are less than five acres each.

Three solar farms recently approved span between 13 and 17 acres.

As solar panel fields continue to crop up, largely in rural areas of North Carolina, counties are grappling with how to best incorporate solar farms with current and future development.

In Brunswick County, solar farms are allowed as a “limited use” in areas zoned commercial-intensive, rural industrial and industrial general. Solar farms are also allowed by special-use permit in rural residential areas.

Representatives of the solar energy industry who spoke to the planning board earlier this week said the current UDO requirements are sufficient.

“The existing UDO is extremely robust,” said Keith Herbs, executive vice president of United Renewable Energy, an Alpharetta, Georgia-based company that builds and maintains solar photovoltaic and energy storage systems. “The UDO that is currently in place is very well thought out.”

The company is the developer of four solar farms currently under construction in Brunswick County. This past summer, United Renewable Energy received permits for three more projects in the county, Herbs said.

Placing a size limit on solar farms restricts the landowner from being able to make a decision on how to best use the land, he said. He urged the planning board to review proposed solar farms on a case-by-case basis.

Herbs said he understands the concept behind establishing a decommissioning plan, but requiring three-year updates, he said, seems redundant on projects that may last 25 to 30 years.

“I think where we feel it can be a little onerous is in terms of identification of who is responsible and timing,” Herbs said.

He said he was not familiar with similar stringent decommissioning plans for other industries such as cellular towers.

Solar farms have a significant scrap value that would almost offset any removal costs upon decommissioning, Herbs argued.

“Part of it has to do with the nature of the business itself,” Hargett said of the decommissioning plan. “It changes. It’s an evolving kind of technology. If the material loses its value it may be that we would need to change the amount of the financial guarantee. Our research does not put faith in the salvage value, frankly.”

Mike Fox, a Greensboro-based attorney representing Cypress Creek Renewables, a solar farm development company with offices throughout the country, said he has seen local governing boards and communities struggle with similar questions and concerns raised in Brunswick County.

“I’m always comfortable with the process of the SUP (special-use permit),” he said. “I would really encourage you not to limit yourself in the future going forward. I would just encourage you to use your existing UDO provisions to control the size.”

Tim Hayes, a manager of engineer, procure and construct, or EPC, projects with Cypress Creek Renewables, said the company will own and operate its solar farms for the long term.

If, for whatever reason, the company discontinues operations, it would recycle the equipment, he said.

“These are very valuable assets,” Hayes said. “We’re not going to abandon this equipment.”

Hargett acknowledged that there is much to be learned about the evolving technology.

“We realize that there’s a lot of moving parts with this,” he said. “There’s a lot that’s not known and a lot that will change. We are committed to solar energy. We have tried to do as best we could as planners to respond to all the various concerns.”