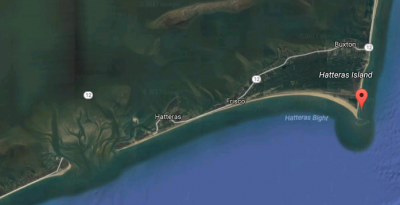

This Google Earth Timelapse shows changes to Hatteras Inlet and Cape Point from 1984-2016.

BUXTON – Whatever mysterious forces crafted the new, crescent-shaped island at Cape Point is at the same time steadily gulping down the south end of Hatteras Island, spitting aside trees, power poles and a popular route for off-road vehicles.

Supporter Spotlight

Thanks to aerial photography and social media, so-called Shelly Island was a summertime sensation, attracting thousands of beach drivers to see the new phenomenon. But 15 miles west-southwest, sand travel has not attracted as much excitement, but it has become a much more serious concern.

Mere months after the sandbar rose seemingly overnight in the late spring from the churning surf off the tip of the Point, a permit has been issued to Tideland Electric Membership Corp. to bury power lines along the rapidly eroding sand road between Hatteras Village and Hatteras Inlet.

With the spit that carries the road dramatically diminished, Hatteras Inlet is no longer buffered from the open ocean, resulting in hazardous shoaling and strong currents that restrict ferry and charter boat traffic. Dare County has recently entered an agreement with the state and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to dredge troublesome parts of the inlet, and the Ferry Division several years ago was forced to change its route because of sand clogging the channel.

Known locally as Pole Road, the sand spit has lost about 1.5 miles since Hurricane Isabel in 2003, and is only about half the length it was in the late 1990s. If erosion continues, it could eventually imperil the state-owned Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum and the state ferry docks.

‘It’s unbelievable, really,” said Heidi Jernigan Smith, Tideland’s manager of economic development, marketing and corporate communications. “There’s no apparent end in sight.”

Supporter Spotlight

Smith said the electric cooperative filed the application with the National Park Service, the landowner, two years ago as a precaution, in case conditions warranted proactive measures.

Although the estimated $3.5 million project, which would bury 1.8 miles of armored cable, is not definite, she said, it seems inevitable. The beach has eroded nearly to the cable riser, where the power lines now carried by overhead poles are attached to the 20,450-foot submarine cable that runs underneath the inlet to Ocracoke Island.

“We don’t see the situation reversing,” Smith said. “At some point, you have this realization that this is the new reality and you have to adjust to it.”

For decades, Pole Road has been a favorite off-road vehicle route to quiet beaches and fishing spots along Pamlico Sound and the inlet. But it has been increasingly plagued by flooding and overwash. While driving on the road in mid-September, even Cape Hatteras National Seashore superintendent David Hallac deemed the road too muddy and flooded to continue to the inlet, where he said the road ends abruptly, as if chopped off.

Wind-bent salt cedar, surrounded by marsh brush and grasses, was clinging to life on either side of the road. The hum of insects and the roar of the ocean was interrupted only by occasional bird calls and the noise of another vehicle bumping by on the rutted road. Observing some lifeless stalks and leaves, Hallac said that is a sign of saltwater inundation and a water table that is getting higher as sea levels rise.

The remains of uprooted trees lost with the fallen-away land lined the shoreline along the ferry channel – a foreshadowing of the fate of the power poles if nothing is done.

“It just shows you how dire this erosion problem is,” Hallac said.

Informal discussions have been held with the Corps, he said, about the possibility of placing dredge material on the south end of Hatteras Island.

Steve Shriver, the Corps’ survey section team leader, said that during the period between 2002 and 2016, the Hatteras spit has eroded about 7,200 feet.

“That’s a lot,” he said.

Shriver said it is hard to say how much the change contributes to the overall increased shoaling problems in the inlet.

“I think there’s generally consensus when that natural spit was out there, it protected the channel that was behind it,” he said. “Because that island has eroded back over the years, it has exposed it to the open ocean.”

Shriver said he couldn’t say if it is possible to rebuild the spit, or even guess how much sand it would take.

“It would be massive,” he said. “It would be a tremendous, tremendous thing.”

Jed Dixon, the deputy director of the North Carolina Department of Transportation’s Ferry Division, said plans are in place to rebuild the beach with dredge spoil by the South Dock basin on Ocracoke, but no plans are yet in the works to address ferry infrastructure on the Hatteras side.

“We’re concerned – anybody who owns property there, I’m sure, is concerned,” he said. “It’s got a long way to go before it impacts our buildings. We’re more concerned about how it’s going to affect our channels if it continues to erode.”

None of the sand comings and goings in Hatteras Inlet or at Cape Point seemed to surprise coastal and marine geologist Stan Riggs, distinguished research professor at East Carolina University who has studied the Outer Banks since the 1970s.

“Basically, that inlet has been filling up over time,” he said. “If you get the right storm, it’ll blow it all out again.”

The Hatteras spit is part of the very dynamic coastal system that is influenced dramatically by the nature and frequency of storms.

“That is nothing but an inlet spit,” Riggs said. “They’re not permanent. They might last for 20 years, they might last for two to three weeks. The dynamics there have gotten ahead of what the dredges can do.

“The reality is that we can’t predict whether it’s going to open up again or it’s going to close back down. What happens is totally a function of the storms.”

Riggs also saw Shelly Island as more of the same.

“Ever since I’ve been here – 50 or 60 years – there’s always been a shoal there,” he said.

He surmises that the lack of nor’easters last winter on the Outer Banks, coupled with more southwest winds than usual, allowed the sand to build up. Again, he said, it will be storms that determine whether Shelly Island, now about 28 acres, grows or disappears as quickly as it materialized.

Meanwhile, thanks to the Internet, the nearly mile-long Shelly Island has been a tourist sensation.

“It has happened numerous times over the years – none of them has ever been as big as Shelly Island,” said David Scarborough, the treasurer for the Outer Banks Preservation Association, a nonprofit group that supports off-road vehicle access. “In 1998, there was a really big island over there. It was about the same place, maybe only half as big as Shelly Island in terms of length. It was there about five months.

“The Point – it changes so much from one year to another,” he said. “Right now it is kind of narrow.”

Access to the Point along the beach from the main entrance at Ramp 44 has become nearly impossible around high tide, when the ocean splashes up to the dunes.

But visitors have managed to come in unprecedented numbers.

On a warm day in mid-September, with blue skies and a light breeze, off-road vehicles were parked along both sides of the triangular beach, which is about a mile from the ramp. Numerous people were wading across the 50-yard or so channel of water from the Point to Shelly Island. Some gathered shells, some fished, and some just walked around. At the southwest end, some people crossed on a tentative sand bridge that materialized at low tide.

Surfers were taking advantage of long breakers on the northeast side created by the new sandbar.

Earlier in the summer, the water was too deep to access Shelly Island without a kayak. Numerous sharks were also seen swimming in it. But it soon started shoaling up in some spots, allowing easier – but still unpredictable – access.

“That’s dangerous,” Hallac said as he observed several people walking through knee-deep water that quickly was up to their waist. The Park Service has repeatedly warned visitors about deceptively strong currents. When people came up to him to chat, Hallac gently cautioned them about the hazards of entering the water.

“What happened here?” Gary Hanning, a visitor from northern Pennsylania, asked Hallac. “I’m just like, ‘Wow!’ I’m still in awe,” Hanning exclaimed.

The park superintendent himself was still impressed by the dynamics at Shelly Island. A pond of water, propelled by offshore storms, he said, had overnight broken a new channel of water alongside the shoreline.

Back in February, Hallac said, he had noticed waves breaking on a shoal off the beach, but he thought it was just the typical sandbar. He said he never imagined that it would continue to accrete to the size where it emerged from the water.

“In the beginning of May, it dawned on me that this was the beginning of a pretty amazing feature that would persist,” Hallac said.

However long it lasts, the superintendent understands why people have been so entranced by Shelly Island, situated as it is right off one of the wildest, most spectacular beaches on the East Coast. He recalled a recent calm day, surrounded in every direction by sand, the clear, blue-green water glinting in the sun.

“There were a couple of days where the tide was really low,” he recalled. “It was drop-dead gorgeous.”

But things are not so pretty at the very end of Hatteras Island, where waves are crashing on tree roots.

“All the sand has washed away from the root balls – it was just terrible,” said Scarborough. “The tip of the island is gone.”

Front page featured image by Don Bowers, Island Free Press