What would development along the coastline look like if subsidies for infrastructure were taken away? Would it keep homes from being built in high-risk environmentally fragile areas?

The Coastal Barrier Resources Act, or CBRA, enacted in 1982, sought to discourage such development by doing away with federal incentive subsidies for infrastructure – namely water/sewer, roads and flood insurance.

Supporter Spotlight

But development along coastal barriers has continued despite the lack of federal incentives, and a team of researchers at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill wants to know more about why that is happening.

Over the next two years, researchers Todd BenDor, David Salvesen and Nikhil Kazah will be evaluating the effect CBRA has had on development along the coasts of North Carolina and other states.

BenDor, the lead researcher on the project, said one goal of the study is to understand what happens when federal subsidies for development are ended.

“What happens when you end subsidies for infrastructure and flood insurance in high-hazard areas in some places and don’t end subsidies in other places,” he said. “Basically, you create this unlevel playing field.”

While the intent of CBRA was to reduce or slow development in those high-hazard areas, BenDor said state and local governments might be undoing that effort – especially in CBRA areas in or near tourist areas.

Supporter Spotlight

“Our hypothesis is that is happening, that state and local governments are stepping in to basically fill in what the federal government had removed,” he said.

Another goal of the study is to determine if CBRA has worked at slowing development and the role state and local governments have played in picking up where the federal government has left off, BenDor said.

“When does that actually happen?” he said. “We’re not expecting it’s all the time.”

But, he said, it begs the question: What happens when you stop paying someone to not do something they weren’t going to do anyway?

“One hypothesis is that some of these areas that were chosen to be in (the CBRA) system essentially will never develop whether or not they have infrastructure subsidies,” BenDor said. “So, one of the things we’re also interested in is did (the federal government) appear to select areas that were just never really going to develop in the first place?”

Salvesen, who researched CBRA development 15 years ago for his dissertation, said he thinks the study will find that some areas that were desirable for development will develop with or without the federal subsidies.

“What I found last time is that CBRA seemed to have a delaying effect, in that other areas that were not part of the Coastal Barrier Resources Act get developed first, and then finally developers turn their attention to the CBRA areas because that’s all that’s left. And if land values are high enough, and if the market is strong enough, what I found last time is that development will occur there.”

BenDor agreed.

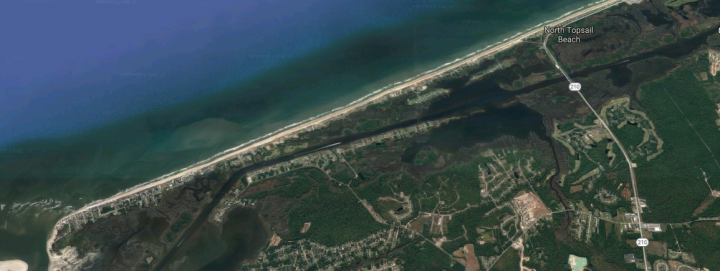

“We’re expecting that some of these areas that had not developed in 1980, a lot of them are close to areas that have (since) become highly developed,” he said. “Topsail Island is a great example of this, where you get spillover from lots of other development around it, and now that area is highly developed even though it’s in the Coastal Barrier Resource system.”

The project could impact the way federal flood insurance and infrastructure subsidies are allocated for environmentally fragile areas besides the coast, as well as the way state and local governments allocate their own subsidies.

“The same kind of approach could apply to, say, floodplains,” Salvesen said. “Local governments could say, ‘We’re not going to provide water and sewer or roads or any kind infrastructure or government services to areas that are deemed risky places to develop.’ They could do that.”

While the CBRA includes areas from the United States’ entire coastline, the project will focus on the coasts of North Carolina, Texas, Florida, Alabama and Delaware for their differences in development patterns, climates, coastal resources and economies.

“In the first couple of months we’ll be doing an inventory of all of the coastal barrier units in those five states and we’ll look and see how much development has occurred,” Salvesen said. “And then we’ll zero in on a handful of CBRA units to do our more in-depth analysis.”

The two-year project, made possible by a National Science Foundation grant, is just getting underway now that students have returned at UNC, Salvesen said.

“We did some preliminary work – we’ve talked to Fish and Wildlife Service, we’ve looked at what data is already available and who else has done studies like this,” he said. “And now that we have students on board, we’re really ready to start sinking our teeth in.”