WINDSOR – Bertie County farmer Fen Rascoe was late getting his hemp seed in the ground – not so late that it will damage the crop, but he had hoped to have his seed planted by early May. It was almost June before the first 10 acres were planted.

There are still more acres to plant. There is seed from Kentucky that will cover another 40 acres. As the first week in June rolled around, it was a waiting game, with Rascoe hoping the rains would ease off just enough to work the fields.

Supporter Spotlight

Seed is also coming from Italy, but that was delayed, lost somewhere between North Carolina and Italy and just found recently in Raleigh.

It’s been a long road, confusing at times, stressful, expensive. But when Rascoe finally did plant his hemp seed, there was a sense of accomplishment.

“It was an amazing feeling,” he said. “It’s the first time in 90 years that it’s been done. It was two years of hard work, but we were finally able to get it in the ground.”

Until 2014, hemp could not be legally planted in the United States. That was the year Congress included Section 7606 of the Farm Bill, allowing states to determine whether hemp is a viable crop.

A year later in September 2015, North Carolina passed Senate Bill 313, the bill that created the North Carolina Hemp Commission.

Supporter Spotlight

Working under the direction of the North Carolina Department of Agriculture, but paid for with private funds, the commission was tasked with developing rules, regulations and fee structures for planting hemp in the state.

No one is exactly certain when the last legal hemp plant was harvested in North Carolina. Eighty years ago? Ninety? There does not seem to be any clear record and farmers are now starting from scratch.

“It’s all trial and error for a couple of years,” Rascoe said.

Natural Resources Program Leader Tom Melton at North Carolina State University is the association chair and he agreed with Rascoe’s assessment.

“We don’t really know what’s going to happen in North Carolina,” Melton said.

At one time, hemp was an important cash crop for North Carolina. During Colonial times the British Navy paid a subsidy of six pounds per acre to make sure they would have fiber for rope. But over time other plants and synthetics came to replace hemp as the first choice for rope, and by the 1930s, hemp was not considered an important crop in the U.S.

There were still uses for hemp: It’s fibers make a good quality paper and take less processing than wood pulp, and for centuries it has been used for clothing. But it’s importance was already on the wane 80 or 90 years ago.

The final noose in the hangman’s rope, however, came in the 1930s.

The problem was its scientific name, Cannabis sativa, the same as marijuana.

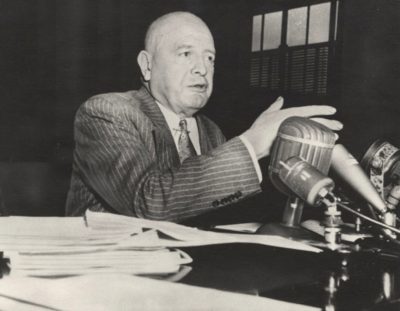

To Henry J. Anslinger, the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, the predecessor to the Drug Enforcement Administration, marijuana was “the Devil Weed.” He attacked it with fervor and hyperbole, linking the drug to sexual licentiousness, violence and a blurring of racial distinctions.

The 1937 passage of the Marihuana Tax Act, a law that taxed any form of Cannabis sativa so heavily that no one could afford to have it in their possession, grouped all hemp plants into one category.

That law was ruled unconstitutional in 1969 but Congress quickly passed the Controlled Substance Act in 1970, classifying Cannabis sativa as a Class 1 narcotic, defined as having “… no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse …”

That classification has been challenged repeatedly by the scientific and medical communities, but Cannabis sativa is still considered a Class 1 narcotic.

Marijuana and hemp may come from the same plant, but there is an important distinction. The difference is the percentage of tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the psychoactive chemical in the leaf of the plant. Industrial hemp planted in North Carolina must have a THC content less than 0.03 percent, whereas psychoactive marijuana plants contain 5-20 percent THC by weight.

Hemp, as a commercial commodity, has been expanding, and the original uses for the crop have grown far beyond rope, clothing or paper. Building materials, insulation in cars, bedding for pets, a food source, medicine … more than 25,000 uses for the plant have been identified.

The plant has become an international billion-dollar industry that is projected to continue to grow, and until 2014 when Congress attached Section 7606 to the Farm Bill, American farmers were shut out of the market.

No one knows just how strong the market is going to be. Keith Edmisten, professor of crop science at N.C. State, has taken on the academic role of examining the viability of hemp in North Carolina, and his observation seems to mirror the concerns of farmers.

“There’s a lot of interest and some demand. How much acreage it will support remains to be seen,” Edmisten said.

There are about 31 licensed growers, 790 acres and 77,973 square feet of greenhouse in North Carolina. “All of those may not plant, and there are some that have not paid fees yet so are not licensed. But it’s a rough idea,” Melton said.

Rascoe, who serves with Melton on the board of the nonprofit North Carolina Industrial Hemp Association, a trade and lobbying group, was an early advocate for planting hemp in North Carolina, but he, too, seems to be taking a cautious approach.

“I probably ordered enough seed to plant 100 acres,” Rascoe said. “I’ll plant 60 then freeze the rest for next year.”

There are questions still to be answered.

Different uses entail different ways to grow the crop. Hemp grown for fiber is planted very densely, much like wheat. There is also an emerging market for seed products such as oil and food. Seed hemp is planted at half the density of fiber to allow the plants to come to a head.

The fastest growing market, however, is for medical marijuana. THC is a cannabinoid, but is just one of more than 100 cannabinoids in hemp plants.

Some cannabinoids may have medicinal uses, but do not have the psychoactive traits of THC. Cannabidiol, or CBD, has become one of the most studied cannabinoids and is often cited as perhaps the most important component of medical marijuana.

There are also unanswered questions about the growing conditions required by CBDs and hemp grown for medical uses is often grown in a greenhouse. Nonetheless, Chris Cobb, who is planting 60 acres of hemp in Bertie County, is going to experiment with a small amount of medical marijuana.

“I’m planting about two acres of CBD,” he said. “I’m hand-picking my spot.”

It’s unclear how successful hemp will be in North Carolina, and as the seed goes in the ground there is hope and concern in equal measure.

“There’s always going to be a front-runner,” Cobb said. “And it looks like Bertie County is going to be the biggest on the eastern side of the state.”