WILMINGTON – Long before Eagle Point Golf Club caught the attention of PGA officials for the site of the 2017 Wells Fargo Championship, May 1-7, the course was in a different type of spotlight. Three years after opening, the club donated 218 acres as a conservation easement to the North Carolina Coastal Federation in 2003. By promising to preserve the land in a natural state adjacent to Middle Sound, the club was left with just 13 acres to control for its facilities.

What captured public attention was not the protection of a priceless shellfish estuary but the club’s $16 million tax deduction. The value of a conservation easement is the difference between the market value of the property before and after the easement restrictions are implemented. The result is a tax deduction for the lost market value of the land determined by an independent appraiser.

Supporter Spotlight

Putting aside land for conservation and obtaining a tax break is a common practice. In 2012 alone, the IRS reported that almost $1 billion in conservation easements were donated.

During the succeeding years, Eagle Point’s owners have demonstrated that their donation was more than just a one-and-done financial transaction. The club has annually implemented ongoing environmental improvements, both independently and with partners.

And unlike other golf courses that have donated conservation easements, Eagle Point has no homes lining the fairways. And it never will.

As part of the conservation easement deal, the club agreed to semi-annual inspections by the Coastal Federation. To improve stormwater drainage, the club’s maintenance staff installed buffer zones preventing pollutants from entering Little Creek and feeder creeks. Little Creek flows directly into Middle Sound behind Figure Eight Island. Vegetative barriers were planted around ponds, native grasses replaced managed turf and a closed-loop stormwater pond system was upgraded.

“Conservation measures taken by the Eagle Point Golf Course greatly minimized stormwater runoff into adjacent Little Creek and the estuary,” said Tracy Skrabal, coastal scientist at the federation’s Wrightsville Beach office.

Supporter Spotlight

That was the good news. The bad news was that the quality of water entering Little Creek continued to decline. Polluted stormwater from the Porters Neck Development, new residential neighborhoods and added roadways was funneling into Eagle Point. The main culprit was fecal coliform bacteria from domestic and wild animals, along with fertilizers.

Eagle Point elevated its game in 2009 to meet the challenge.

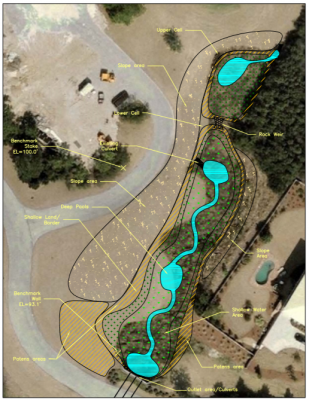

A partnership with the federation, New Hanover County, North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina Wilmington resulted in a new stormwater wetland and two bio-retention areas.

NCSU Professor Michael Burchell and his team created a master stormwater-management plan that identified potential low-impact stormwater-reduction projects. The report also said to pay attention to the needs of golfers.

“Input from the membership will be crucial to get support. It’s important to evaluate how wetland areas might affect play. Wetlands that can act as lateral or water hazards while providing an aesthetic amenity around the course that can be highly desirable,” the report stated.

Burchell’s team also stated that improved course drainage would decrease course damage and allow players to return to the course sooner after heavy rains. And polluted stormwater would be contained and allowed to infiltrate into the ground, protecting the nearby estuary.

Before acting on Burchell’s recommendations, UNCW’s Michael Mallin established a baseline by collecting water samples. The UNCW team found no excessive levels of nitrogen fertilizers. “The course was being managed very responsibly – there was no over loading. However, we did find a lot of fecal chloroform bacteria that was washing onto the course from offsite developments,” Mallin said.

The most needed bio-retention area was created with the help of 75 volunteers. Thousands of lizard’s tail, bullrush, sedges and marsh grasses were planted where drainage pipes dumped contaminated stormwater from an adjacent 750-acre community. When the club’s owners purchased the land for the golf course in 2000, allowing the drain pipes to remain was part of the deal.

“This was absolutely a demonstration project. Not just for golf courses, but for other pieces of land that receive stormwater from neighboring properties,” said Skrabal, who was the project’s manager.

Following the project’s completion, Skrabal said the club invested heavily in further improvements. “Eagle Point has done a ton of work and spared no expense in putting in additional buffers around water areas and replacing fairway turf with vegetation,” she said.

On a golf course, less turf translates into fewer chemicals, and improved water quality.

Mike Giles, coastal advocate with the federation, has conducted the semi-annual visits to Eagle Point for the last 10 years. During and after those visits, the course owners have consulted with him about plantings and improvements.

“When we recommend certain sizes, they usually put in specimens three times larger. The most popular plants selected include palmettos, marsh grasses – native and non-native – wax myrtles and yaupon hollies. They’re all great for improving water quality,” he said.

With this year’s Wells Fargo Championship, the course has required some significant changes to accommodate PGA players, spectators and a national television audience. Eagle Point Superintendent Craig Walsh has worked with Giles to make temporary adjustments including moving trees, plants and turf.

“They spaded and moved a few 30-foot magnolia trees and put down turf for spectators to walk. But they’ll move those trees and plants back after the tournament. It’s been a good partnership,” Giles said.

PGA officials are likely to take note of Eagle Point’s balance of form and function in handling stormwater. Last year, a PGA publication stated, “Water features are more than design elements or water-storage areas; they are living systems that can add ecological and aesthetic value to a golf course.”

What’s next? Giles said Eagle Point is looking to install sturdy plants under the canopy of large live oak trees located in a strategic stormwater runoff area. On small bluff and hills, the club would like to install low growing plants that people could walk on instead of turf.

“Eagle Point is doing it right. They’ve taken the time to consult with one of the area’s leading experts on native plants,” Giles said.

These course changes have not hurt Eagle Point’s reputation. Since 2009, the course has made Golf Digest’s annual list of “America’s 100 Greatest Golf Courses,” proving that an environmentally friendly golf course can also be a beautiful and challenging place to play.

And for those wondering about the financials associated with conservation easements, Mallin said, “If that golf course was not there, I am sure it would be full of condominiums today.”