Reprinted from the Tideland News

Audubon North Carolina recently announced two new programs the organization says can help the state’s birds survive as the effects of climate change become more severe.

Supporter Spotlight

Curtis Smalling, director of conservation for Audubon North Carolina, said the two programs – Climate Strongholds and Climate Watch – offer ways for state agencies, nonprofit conservation groups and, of course, individual property owners, to make a difference.

In addition, Smalling said, involvement in such bird-related programs and efforts can serve as vehicles to make people more aware of climate change issues in general, and more likely to try to influence public policies that can hurt or help not only birds, but also the crucial ecosystems that those birds – and people – rely upon.

Heather Hahn, Audubon NC executive director, said the effects of climate change on birds are already noticeable.

“We’re already seeing birds shift where they can live due to changes in weather brought about by climate change, with 60 percent of our wintering birds spending their time further north than just 40 years ago,” she said. “We are starting the (new programs) now to identify and protect valuable land and habitat that birds will need in the future to survive and thrive. It’s critical that our birds always have a place here in North Carolina.”

Climate Strongholds

Smalling and Hahn said data gleaned from the 2014 Audubon Birds and Climate Change Report have allowed Audubon scientists to identify five regions of North Carolina where birds are expected to seek sanctuary from the effects of our changing climate. These “climate strongholds” can offer the right mix of temperature and precipitation needed to support a wide diversity of birds now and into the future.

Supporter Spotlight

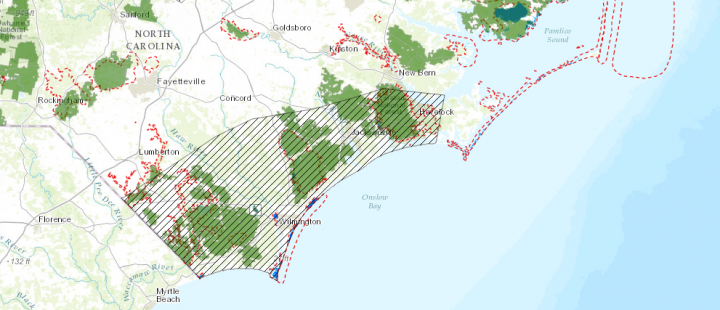

Climate strongholds represent regions of the state that are expected to retain suitable climate conditions required by climate-threatened birds with diverse habitat needs. Audubon NC Climate Stronghold regions include the Blue Ridge Mountains, Capital-Piedmont (greater Raleigh), Roanoke and Chowan Rivers Bottomlands, and the Southern Coastal Plain. Audubon modeled an additional “Coastal Stronghold,” to identify which existing Important Bird Areas, zones deemed important for conservation of bird populations, are most threatened by sea-level rise.

“For the first time, we’re able to apply data to predict where birds will move as the climate changes,” Smalling said. “Knowing where birds are likely to move in response to climate change will guide future bird conservation in North Carolina, and we’ll need lots of partners to be successful and will assist our partners in protecting land and managing bird habitat in the state.”

Working from this future blueprint for conservation planning, Audubon NC will prioritize work with partners to conserve natural areas within these climate strongholds, manage forests in a bird-friendly way and grow bird-friendly native plants to protect our most climate-threatened birds.

Smalling said examples include working with organizations such as the North Carolina Coastal Land Trust or the North Carolina Coastal Federation to preserve critical habitat, and working with state and federal agencies to help make good decisions. He called it a “no-regrets” approach, since the same conservation efforts and policies that can help birds also help the environment.

The coastal climate stronghold, Smalling said, may be facing even more immediate threats than most of the other strongholds, in part because not only is the weather changing, sea level is rising, inundating marshes and reducing flat, sandy beach areas that serve as habitat for shorebirds.

But Smalling stressed that it’s not just up to conservation groups and government agencies. In fact, he said, there are countless meaningful, although seemingly small, ways for property owners to help.

A big way is to rely, as much as possible, on native plants in landscaping.

Smalling said a native oak tree supports 600 insect species, whereas a non-native crepe myrtle supports only three. That makes a huge difference to birds, many of which rely overwhelmingly on insects for food.

Another way is to plant-bird friendly species in gardens. People can also try to reduce bird-window collisions, particularly in urban areas, but keeping lights off at nights. And people everywhere can do birds a big favor by keeping cats inside as much as possible.

Again, he stressed, birds can be a good entry point for conservation in general.

When “people feel like they can actually do something that makes a difference,” he said, they start taking personal responsibility, and personal responsibility can and often does lead to advocacy, things like contacting local officials and legislators and urging them to take steps that help habitat, as well as urging them not to take steps that result in habitat destruction.

Examples of policy decisions include beach nourishment and the use of groins or bulkheads to slow erosion along the coast. In that sense, it’s not just climate change that threatens birds and habitat, but man’s response to climate change. Such hardening of the coast reduces habitat, whereas living shorelines can slow erosion and preserve or even create habitat.

One of the goals, Smalling said, is to simply make people more aware of the threats climate change poses. Sometimes these changes aren’t obvious.

For example, people may say, “I still see birds” on the beach, but might not notice that their numbers are lower than in the past, or that they are around at different times, or not around for the same length of time.

Climate change has always happened, he noted, but the “pace seems different now,” and one of the goals of climate strongholds is to slow the effects of those changes enough to give birds more of an opportunity to adapt, as organisms have always done.

Climate Watch

The Climate Watch effort is a program that builds upon more than 100 years of Audubon “citizen science” to track and document the health of bird populations. It aims to track the response of individual bird species to climate change to inform future conservation planning.

Audubon recently announced that its 2014 Birds and Climate Change report revealed three species of North Carolina nuthatches – red-breasted, white-breasted and brown-headed – that are among 170 bird species in the state whose ranges are expected to shift and significantly shrink because of a changing climate.

In the program, volunteer Audubon members and other lay scientists count nuthatches during two observation periods, Jan. 15-30 and June 1-15. The volunteers then report their data to a national database for analysis.

“Projects like this one keep the ledger of how birds are being affected by climate change,” said Kim Brand, Audubon NC field organizer. “Over time we’ll be able to see how bird populations respond to climate change and adjust our conservation strategies accordingly.”

Learn More

This story is provided courtesy of the Tideland News, a weekly newspaper in Swansboro. Coastal Review Online is partnering with the Tideland to provide readers with more environmental and lifestyle stories of interest about our coast. You can read other stories about the Swansboro area here.