WILMINGTON – The Army Corps of Engineers has authorized its first nationwide permit for living shorelines.

Nationwide Permit 54 specifically addresses the construction and maintenance of living shoreline projects.

Supporter Spotlight

The new permit solidifies on a national level the value of living shorelines as a more natural erosion control alternative to hardened structures such as bulkheads, say living shoreline advocates.

“We’re really excited about this,” said Laura Lightbody, project director of The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Flood-Prepared Communities program. “Our hope is that this nationwide permit will ease [the permitting process] for property owners, giving them more of a choice hopefully leading them down the path of the environmentally preferred option.”

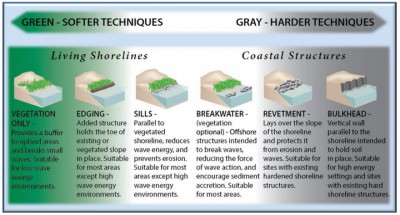

Living shoreline projects are built with various structural and organic materials, such as plants, submerged aquatic vegetation, oyster shells and stone. These projects generally work best along sheltered coasts such as estuaries, bays, lagoons and coastal deltas, where wave energy is low to moderate.

The Corps has folded permitting guidelines for living shorelines into Permit 13, which governs construction of erosion-control projects.

The problem with the current permitting system, critics say, is that in areas including North Carolina, those who apply to build bulkheads and revetments have an unfair advantage because it takes generally less time and money to obtain permits for hardened structures than for living shorelines.

Supporter Spotlight

The Corps’ Wilmington District has regional General Permit 291 that covers shoreline projects in or affecting navigable waters. This permit was developed in conjunction with the North Carolina Division of Coastal Management and was one of the first state programmatic general permits authorized in the country.

The way the system is set up now, general permit applications have to be reviewed by the state Division of Water Resources and Division of Marine Fisheries. After those state agencies have reviewed an application, the applicant must then submit it to the Corps for authorization.

Because this puts the burden on the applicant, most apply for a Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, major permit, which is, in essence, a one-stop shop where the state Division of Coastal Management sends an application to all of the reviewing agencies. The review time for CAMA major applications takes 45 days or longer.

General Permit 291 will continue to be available for coastal projects, including living shorelines, according to a Wilmington District public affairs officer.

“If a project involves a CAMA major permit and agency coordination is needed for historic properties, endangered or threatened species or essential fish habitat consultation, we will more than likely process living shoreline projects under GP 291,” Lisa Parker, wrote in an email responding to questions.

Permit 54 specifies a time frame in which the Corps must review a request and respond to an applicant, which will help streamline the permitting process.

With a more streamlined permitting process, Lightbody said the hope is that living shorelines will buck the trend of hardened erosion-control structures.

At least 14 percent of the country’s shoreline is armored by hardened structures, according to a group of researchers who in 2015 conducted the first nationwide survey of artificial coastal erosion control methods.

That’s more than 14,000 miles of hardened shoreline.

“We don’t want that to increase and continue down the path that it’s on,” Lightbody said.

If hardened shoreline structures remain the status quo and the coastal population continues to grow, nearly one third of the nation’s contiguous shoreline is expected to be hardened by 2100, according the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s “Guidance for Considering the Use of Living Shorelines.”

The guide, published in 2015, explains why living shorelines, when built in areas suitable for natural stabilization, are a preferable alternative to hardened structures.

Mounting research shows that living shorelines hold up better through storms than hardened structures, enhance intertidal habitat for fish and other marine resources, and better defend against sea-level rise.

Permit 54 states that living shorelines “should maintain the natural continuity of the land-water interface, and retain or enhance shoreline ecological processes.” The permit further states that living shoreline projects must have a “substantial biological component” that should include tidal or lacustrine fringe, or lakeside, wetlands, oyster or mussel reef structures.

Conditions of the new permit require an applicant to build out no more than 30 feet into the water from the mean low water line in tidal waters and no more than 500 feet in length along the bank, unless waived by a Corps district engineer.

Structural materials such as stone, native oyster shell and wood debris must be anchored so it does not move in “most” wave action.

The new permit also mandates native plants be used in living shorelines constructed in tidal or lacustrine fringe wetlands.

The Corps can place conditions applying to specific regions on nationwide permits, or NWPs.

“Regional conditions for the NWPs are still under review and at this time we do not know what the regional conditions will be for NWP 54,” Parker wrote.

The goal, she stated, is to have regional conditions in place by the time the existing nationwide permits expire later this winter.

The Corps issues nationwide permits for a whole host of activities covered by the federal Clean Water and Rivers and Harbors acts. The review of applications for such permits is streamlined because the activities will have minimal effects on the environment.

NWP 54 is one of two new nationwide permits the Corps released Jan. 6. The agency updates its national permits every five years. New and modified permits will become effective March 18.