With much of the Atlantic and Arctic waters no longer up for grabs for offshore drilling, the U.S. is on the right track to keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius by 2040.

That’s according to a study, prepared by Seattle-based researchers at the Stockholm Environment Institute in cooperation with the Carbon Tracker Initiative, a think tank working to limit future greenhouse emissions, that shows any future drilling of oil or gas in the Atlantic and Arctic oceans would push global warming to 4 degrees or beyond.

Supporter Spotlight

“The only way (offshore) drilling makes sense is if we fail on climate and force high oil prices on our children and go backwards on the promise of clean energy, which is already knocking on our door,” Franz Matzner of the Natural Resources Defense Council told reporters during a December press call.

World leaders agreed last year in Paris to the 2-degree threshold. And just before leaving office, President Obama, using his authority under the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act, permanently withdrew about 115 million acres of federally owned land in the Arctic and about 3.8 million acres of the Atlantic Ocean from new offshore oil and gas drilling leases.

Now there’s speculation that President Trump could move to undo Obama’s decision. Oil industry advocates are hopeful for such a reversal, which would likely require congressional action and almost certainly face legal challenges.

The drilling ban in the north and mid-Atlantic Ocean extends from New England to Virginia. Waters off the coast of Virginia and North Carolina were pulled previously from Obama’s five-year energy plan, but that ban will expire in 2022.

“Protecting and preserving our Arctic and Atlantic waters embraces the promise of (a) clean energy future,” Matzner wrote following the announcement of the drilling ban last month. “It embraces the notion that we will succeed in meeting the challenge of climate change, not turn backwards on progress or shirk our responsibilities to future generations.”

Supporter Spotlight

Michael Lazarus, a senior scientist at the Stockholm Environment Institute and co-author of the report, said during the December press call that although the Paris Agreement was adopted last year, the U.S. now ranks first in the world in oil and gas production, with one-fifth of the total coming from lands and waters the federal government leases to private producers.

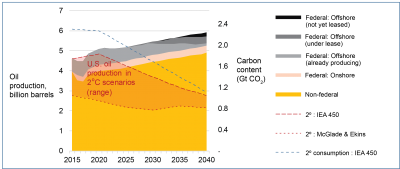

But to keep global warming below 2 degrees, Lazarus said U.S. oil production would need to drop to nearly half its current levels by 2040 and that new leases on offshore oil and gas just wouldn’t make sense.

“It’s clear that Arctic and Atlantic resources are way too expensive and don’t really make sense and are consistent in a future … that is more like 4 degrees and perhaps even 5 degrees (of global warming),” he said.

Lazarus explained two related risks of continued U.S. offshore oil development: “carbon lock-in” and “stranded assets.”

Carbon lock-in occurs when carbon-intensive investments become difficult to walk away from in the long term – for economic, institutional and/or political reasons. Because offshore oil has very high upfront costs, but relatively low operating costs once platforms are in place, Lazarus said investments in this infrastructure are particularly susceptible to carbon lock-in.

At the same time, if global demand for oil declines, as would be expected on a 2-degree pathway, offshore oil investments could easily become “stranded” – meaning they fail to achieve the expected returns, potentially creating economic losses for investors and local communities.

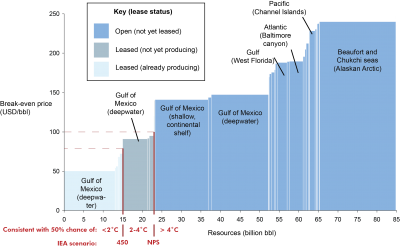

“We found in our study that projects dependent on new leases in the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic, the Pacific, Arctic, appear to require on average break-even oil prices of at least $140 per barrel,” he said. “That’s quite a bit over today’s prices and that’s $50-per-barrel higher than would be cost-efficient if oil demand follows the 2-degree pathway based on the various studies we looked at (for the report).”

“So, indeed, only with demand more consistent with global warming of about 4 degrees or higher and no further climate policies or ramping up of ambition, only then would oil prices be high enough to yield some additional offshore oil from new drilling – only some.”

Dan Lashof, chief operating officer at the nonprofit NextGen Climate America, posed the question, “Is it feasible to transition our economy away from fossil fuels quickly enough to live within a 2-degree carbon budget?”

“The answer to that question is: absolutely yes,” Lashof told reporters.

NextGen is an advocacy group that works to put low-carbon energy sources on par, competitively, with fossil fuel interests.

“Until recently, the prospect of transitioning to a 100 percent clean energy economy would have been considered aspirational at best, particularly when it comes to oil, which, after all, currently powers more than 95 percent of our transportation system,” Lashof said. “But that really has changed in the last couple of years both in terms of the analytical rigor demonstrating the ability to make that transition and the real-world evidence in the marketplace that this is feasible an already underway.”

He cited as an example California, where state law now calls for 50 percent of the state’s electricity to come from renewable energy by 2030 and requires a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050.

Lashof also noted the Tesla’s long-range electric car, Model 3, which got 400,000 preorders in the weeks of its unveiling, and the Chevy Bolt, the price tag for which is about average for new cars sold in the U.S.

Likewise in North Carolina, the town of Boone unanimously passed on Dec. 15 a resolution calling for 100 percent clean energy in North Carolina by 2050.

“The reality is that the technology is here to make the transition to clean energy – the climate data only gets worse month-by-month, showing that we must make that transition,” Lashof said. “And as we make that transition, it only makes sense to put off limits offshore oil from the Arctic and Atlantic – that we cannot afford to burn and stay within any reasonable climate budget.”