First of a multi-part series

Although floodwaters from Hurricane Matthew receded a little more than a month ago, the storm’s effects will linger for years. And if past is prologue, experiences from the disaster will reshape planning and practices at all levels of government.

Supporter Spotlight

In North Carolina, policy changes large and small tend to follow major storms and Matthew and the extensive inland floods that followed certainly qualify, with 29 storm-related deaths and damage estimates climbing above the $2 billion mark.

This week, the Hurricane Matthew Recovery Committee finishes its initial round of community meetings. McCrory announced the committee’s formation in late October and convened the first meeting in Raleigh on Nov. 1. The committee has been trying to gauge local needs above what’s likely to be funded through state and federal disaster aid.

Meanwhile, additional federal aid is in the works on top of what is already flowing. A running tally kept by State Emergency Management put the total in direct aid to victims of the hurricane at $79.6 million.

Since the 48 counties affected by Matthew have been officially declared federal disaster areas, the federal government will pay for the bulk of disaster relief, but the size and scope of the storm, already among the costliest in state history, will require substantial funds from state and local coffers.

The McCrory administration submitted to Congress on Nov. 14 its updated estimate of the cost of the storm, asking for more than $1 billion in federal support. The request includes more than $810 million for community block grant disaster assistance; $40 million for the Army Corps of Engineers to restore federally authorized navigational channels; $41.6 million for dam safety; $22 million in highway funding; and $111 million for farm conservation and watershed-protection projects.

The request is being combined with requests for disaster aid from West Virginia and Louisiana for floods earlier in the year and from other states affected by Matthew.

Right now, the status of federal disaster aid is in a kind of end-of-session limbo. While Congress is likely to pass a continuing resolution on or before its scheduled departure date of Dec. 16, there’s no guarantee that the aid proposals will be included in the bill. Congressional leaders have yet to decide on whether to allow the aid package and other spending to be added or pass a “clean” continuing resolution, which would shift the proposal to the next Congress.

The timing of federal aid could affect what steps North Carolina takes in adopting its own recovery package. Although the governor had previously said he’d prefer to call a special session of the General Assembly after knowing what steps Congress might take, McCrory said this week he intends to call a special session next week regardless.

“We’re waiting on Washington,” Rep. Pat McElraft, R-Carteret, said. While a session seems probable, she said, the date is still a question mark. “I wish they’d set a date if we’re going to do it.”

Sen. Bill Cook, R-Beaufort, said he’s still skeptical that a session will happen. “I’m not sure we’re going to have a session,” he said after a committee hearing Tuesday. “We might, but right now I don’t know.”

Cook said whatever funding comes will be focused on getting roads repaired and finding ways to make recovery efforts move more quickly.

“I’m going to make sure the infrastructure primarily is repaired as quickly as possible and the lives of my constituents are not impacted to this extent in the future,” Cook said.

The state has funded extra material and personnel costs through its two main emergency funds, but has yet to tap into the state’s Savings Reserve Account, the so-called “rainy day fund.” To do that, McCrory needs to get legislative approval.

In advance of the special session, state agencies are preparing cost estimates and strategies for moving ahead once the state and federal funding are settled.

The state budget office has estimated that the state has enough in its emergency funds to last through mid-February. The next legislative session begins the two-year budget cycle, but a final plan isn’t expected until long after the funds are exhausted.

Call For Policy Changes

As with previous responses to major storms, what happens after Matthew is destined to be far more than just providing funds to rebuild.

Throughout the storm, the similarities between Matthew and Hurricane Floyd in 1999 were apparent. Both will be remembered for the intensity of inland flooding, with some areas hit in 1999 again underwater. But in some instances, changes put in place since Floyd made significant difference in the extent of the damage.

One standout difference was the reduction in the number of hog operations that were affected by the floods, the result of both better forecasting and a state buyout program under the Clean Water Management Trust Fund. The buyout moved dozens of operations out of the 100-year floodplain.

The most noticeable difference between the two storms was technology driven.

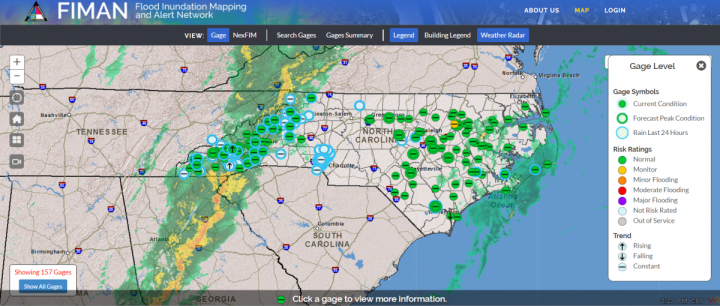

Through the storm, emergency workers repeatedly credited the state’s Flood Inundation Mapping Program and Alert Network with saving lives by predicting in real time and with improved accuracy where and when waters would rise.

The network proved essential given how difficult it was to predict the storm’s exact path. Tracking rainfall and river and stream gauges, the new software helped the state better deploy swift water rescue teams and stockpile supplies closest to the areas hardest hit.

Improving the network and using improvements in technology for better analysis for floodplain mapping and flood prediction is one of the key recommendations being proposed by a coalition of environmental organizations as part of a new “Build Better” plan that outlines a number of steps based on experiences during Matthew, including the effectiveness of policy changes implemented after Floyd.

Grady McCallie, policy director for the North Carolina Conservation Network and one of the main authors of the recommendations, said the working document is intended to get policymakers thinking about future innovations that could reduce damage from another major storm. Utilizing improvements in floodplain mapping, such as the mapping network, is a key theme, he said.

“North Carolina has done an amazing job of investing in our data infrastructure to understand our floodplains and the danger of the water,” McCallie said. “What we haven’t done is connect that to the forward-looking decisions we make. So, when the state’s investing in infrastructure or local governments are permitting land use, those decisions ought to be informed by that information.”

Right now, McCallie said, public policy looks backward. Insurance costs and land use rules make it hard to build in places that have flooded in the past, he said. “Using those (mapping) systems, we can predict what will be flooding in the future and we’re not doing that.”

Other proposals in the Build Better plan include bolstering current programs, such as increasing buyout programs for properties in the floodplains and a substantial increase for the Clean Water Management Trust Fund to improve water and sewer infrastructure. The plan also advocates exploring major policy changes. One idea is to create a legal framework for providing coastal property owners facing an inevitable loss from erosion some form of property tax relief through coastal retreat easements, which would set parameters for the orderly removal infrastructure such as storage tanks and septic systems.

A draft of the document, which includes about 20 separate proposals, will go out to policymakers ahead of the special session, but McCallie said he doesn’t expect to see much action in the short run.

“It would be great if some of the proposals could be dealt with as part of a recovery package, but most are more likely to be dealt with over a longer term.”

Friday: Matthew’s environmental effects