OREGON INLET — If fishing reefs are the underwater version of condominiums, then the waters here will soon be the trendy new neighborhood for marine life.

Construction of a living shoreline reef is underway, to be followed in a few years by restoration of four existing reefs with demolished bridge material. And an entirely new reef is also being planned nearby in state waters, thanks to a grant funded by fishing license fees.

Supporter Spotlight

Technically a habitat enhancement site for submerged aquatic vegetation, or SAV, the living shoreline reef is a wave-break structure that will create a 50-acre “wave shadow,” said Kathy Herring, environmental program supervisor at the North Carolina Department of Transportation’s Natural Environment Section.

The reef, with an inverted V-shape design, reduces the energy in the shadow, allowing submerged aquatic vegetation acreage to increase, she said. In turn, the ecosystem benefits from improved water quality, more aquatic habitat and reduced sediment travel.

“Seagrass don’t like a lot of wave action,” Herring said. “The concept is it will create a calmer environment on the lee side to promote SAV growth. It will double as a living shoreline.”

Aquatic plant growth, she said, is influenced by water depth, light penetration, nutrient loading, salinity, exposure to waves and currents, and is vulnerable to extreme storm events

Located about a mile west of the Herbert C. Bonner Bridge, the 4-foot-high, 500-foot-long reef is part of the bridge-replacement project that Herring said is expected to be completed in 2019. It is the first time the state has set out to build a living reef to promote submerged aquatic vegetation growth instead of standard mitigation practices. The five-year, $2.2 million project is intended to offset 1.3 acres of aquatic plants affected by the bridge work.

Supporter Spotlight

“As well as being a permanent ‘living’ structure, providing bio-habitat for a diverse array of organisms,” Herring elaborated in an email, “this project is part of an effort to determine the best strategy for SAV conservation in NC.”

An important part of the SAV Habitat Enhancement Project, Herring said, is the requirement for five years of post-construction monitoring and reporting. Yearly surveys will be conducted to measure submerged aquatic vegetation growth and to determine the type and number of organisms using the structure.

The structure – built 4 feet off the sea floor – is made of layered units of stacked concrete with natural rock embedded in it, Herring said. Each unit has a hole in it. The selected area has good water depth and light attenuation, she said. Depth at low tide is about 2 to 3 feet. There will be no fishing or access restrictions on the reef, which will be visible above the water and properly marked.

Contractor CSA Ocean Sciences of Stuart, Florida, began construction last month, and is expected to complete the project in about three weeks, weather permitting.

“Man, it looks like great fish structure to me,” said Mac Gibbs, retired county extension director for Hyde County Center of the North Carolina Cooperative Extension Service and a North Carolina Coastal Federation board member, after watching the contractor work one recent afternoon. “The way it’s designed, fish can hide right in it.”

Although the project is not related in any way to the state Division of Marine Fisheries’ artificial reef program, Gibbs, a lifelong fisherman, said he expects the reef to attract a multitude of finfish, as well as oysters. Oyster spat would likely land nearby on Crab Slough in the inlet, he said. The reef would be readily accessible to boaters transiting “the Crack” channel between the Oregon Inlet Fishing Center and Old House Channel.

“It’s going to be great for the recreational fishing community,” he said. “It’s going to have a great benefit on the environment.”

New Life for Old Reefs

Anglers can also look forward to much improved fishing in the near future on four deteriorating reefs, ranging from 2.5 miles to about 4 miles off the beach. Debris from the demolished Bonner Bridge will be used to build up the old structures as the structure is torn down, work targeted to begin by late 2018 and continue for about 10 months.

Jason Peters, artificial reef coordinator for the state Division of Marine Fisheries, said that NCDOT estimates a total of 80,000 tons of suitable material will be available to distribute among the reefs.

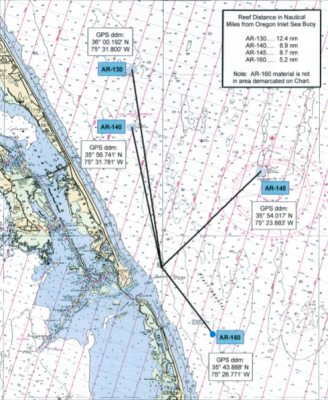

Marked on the artificial reef map, reef No. 160, located south of the inlet and the only one in state waters, will receive 55 percent of the material. Each of the remaining three, Nos. 130,140 and 145 – all northeast of the inlet – will each receive 15 percent.

“That’s a benefit to both – it saves DOT a ton of money,” Herring said. “And it enhances Marine Fisheries’ artificial reef program.”

Peters said that because of the remoteness of the Outer Banks and its harsh coastal conditions, maintenance of the reefs over the years has been lacking.

Currently, there are just the four artificial reefs in waters north of Cape Hatteras, not including the living shoreline.

“Historically, those reef sites have been somewhat underserved,” he said.

There are also seven artificial reefs between Hatteras and Cape Lookout.

As the old bridge roadway is cut into sections, the debris will be placed on a barge to transport to the reef.

Research has shown that marine life wastes no time moving into its new home, Peters said. It might be hours, maybe even minutes.

“It’s like the oasis in the desert,” he said. “A lot of the fish there are reef-oriented. So when that material shows up, they go right to it.”

Soon, there will be the “base communities” – algae, corals, barnacles, mollusks – that create nice hiding spots for the little creatures which move in next. Then come the larger animals, which see the little creatures as dinner. And so it goes.

“The actual establishment of an ecosystem takes several months,” Peters said.

Meanwhile, an additional reef is being planned about 2 miles south of reef No. 160, or 8 miles south of Oregon Inlet buoy, about a ¾-mile distance from the shoreline.

When the Outer Banks Anglers Club learned from Peters that grant money would be available to build an artificial reef in state waters near the inlet, the nonprofit group, which promotes “safety, good fellowship and true sportsmanship among all anglers,” didn’t hesitate to apply, said club president L. Pace Mimms.

“There’s a clear danger (that National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) will make it a protected marine habitat,” Mimms said, elaborating on part of the club’s motivation.

The Anglers Club expects to hear any day whether the $1.2 million grant, which is funded by state recreational fishing license fees, has been approved, he said. An additional $50,000 is being raised to put toward related costs for the project.

If the go-ahead is given, the plan is to sink two retired vessels – one a 100-foot and the other a 200-foot ship – to anchor each end of the reef. They would be sunk by opening the seacock, a valve in the vessels’ hulls. Once sunk, they’ll be anchored. In the middle, the builders will sink 200 tons of used concrete pipe. The following year, another 800 tons of concrete pipe will be sunk on top of that. The reef will rise 25-30 feet above the ocean floor in about 70-foot-deep water, with varying heights to attract different kinds of marine animals. The proposed structure would have a 1,500-foot circumference and lay within 162 acres. It will be easy to reach for skiffs, kayaks and other smaller-sized vessels.

“What we’re planning is a state-of-the art artificial reef,” Mimms said. “It’s going to be a great place for fish, and a great place for divers. I think it will have tremendous impact.”

Once the funds are secured, the vessels – one is likely to be an old tug – will be purchased, cleaned and inspected, Mimms said. Vessels will be towed and sunk professionally, with Coast Guard supervision.

Boats will be oriented northeast to southwest, or vice-versa.

“So, when you fish on top of the these old wrecks, that’s the way the current is going to flow,” Mimms said. That way, the whole length of the boat can be fished.

But anglers will need to be patient.

“It may take some time,” Mimms said. “It’s going to take a couple of years for this thing to grow.”