TOPSAIL ISLAND – Labor Day weekend is normally a three-day opportunity for many to enjoy a beach getaway one last time for the season. This year, while many are watching cautiously as what remains of Hurricane Hermine bears down on the coast, the holiday also marks the 20th anniversary of Hurricane Fran, a deadly, costly storm that washed away homes and popular tourist attractions on this narrow barrier island and along our southern coast.

Hurricane Fran, the sixth named storm of the 1996 season, made landfall just south of Wilmington on the evening of Sept. 5. Fran came ashore as a moderate hurricane, a category 3 storm on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, with 115 mph sustained winds and a 12-foot storm surge. It was the strongest hurricane to make U.S. landfall in decades. The storm dumped 15 inches of rain in North Carolina, causing flooding and slowing cleanup and recovery efforts after it passed.

Supporter Spotlight

Fran killed 24 people in North Carolina and caused more than $7 billion in damage to public and private property. Although Hurricane Floyd three years later would kill more people and do more damage, Fran at the time was the most destructive storm to hit the state seen since Hurricane Hazel in 1954. Hazel remains the only category 4 hurricane to strike North Carolina.

“In Wilmington, Fran is still going to be one of those storms you talk about, unless you can remember Hazel,” said Jay Barnes, director of development for the North Carolina Aquarium Society and author of four books on hurricanes, including “North Carolina’s Hurricane History,” now in its fourth edition.

“One thing that I find, people are always interested in knowing how storms rank against one another,” Barnes said, adding that he explores the topic of North Carolina’s greatest hurricane in his most recent, Aug. 25, blog post at jaybarnesonhurricanes.com.

The various ways to rank storms include meteorological measurements, such as barometric pressure, wind speeds, rainfall and storm surges; property damage inflicted; and lives lost. Barnes puts Fran at No. 3 in his ranking of North Carolina hurricanes, behind Hurricane Hazel and the big No. 1, Floyd. Barnes, in his ranking, cites Floyd’s $6 billion in losses, 66-county swath of destruction and, most importantly, the 52 lives lost.

“On that measurement, Floyd ends up being our greatest natural disaster in our state’s history,” Barnes said.

Supporter Spotlight

Location also factors into the public’s recollection, Barnes said.

Location also factors into the public’s recollection, Barnes said.

“In Carteret County, Fran was just a glancing blow,” he said. “Every storm is different, based on where you live.”

Coastal towns as north as Swansboro and Emerald Isle suffered damage and some flooding during Fran, but farther south along the coast, the storm was far more frightening. Fran’s effects as heavy rains, and to a lesser extent winds, moved inland also caught many by surprise.

According to the National Weather Service, three-quarters of homes in Wilmington sustained some damage from Fran with nearly a quarter of all homes sustaining major damage. Nearby beach towns of Carolina Beach, Kure Beach and Wrightsville Beach also saw flooding from the storm surge and severe damage to homes, fishing piers, public buildings and roads.

Ground Zero

In terms of devastation, Topsail Island and its three towns of North Topsail Beach, Surf City and Topsail Beach were ground zero. Fran’s high winds, storm surge and wave action damaged three-quarters of the structures on the island and destroyed 331 homes.

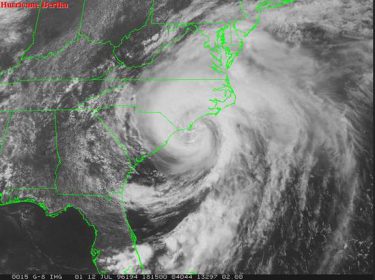

Also destroyed were beloved landmarks, including popular fishing piers. Edwin Lore is owner of Surf City Ocean Pier, Topsail Island’s first ocean pier, built in 1948. Hurricane Bertha did about $30,000 worth of damage to the structure earlier that summer, which was quickly repaired, but Fran destroyed the pier house, which was over the water, and nearly all of the pier itself.

“There was one little 40- to 50-foot section standing,” Lore said.

Lore and his family had evacuated to his hometown of Smithfield, where they were stuck for a few days because of storm debris there, but his pier manager at the time stayed behind.

Edwin Lore of the Surf City Ocean Pier recounts the 1996 destruction of his pier, and temporarily, his business, when Hurricane Fran made landfall. His story is presented as part of The North Carolina Channel’s “Hurricane Fran: A Retrospective.”

“He called me up and I knew what I was going to walk back into – or what I wasn’t going to walk back into. When I got over, of course knowing what I was going to see, it still kind of took me in shock. It was gone,” Lore said.

Lore was 11 years old in 1973 when his father had purchased the pier and it was a big part of his childhood before becoming his career. The business had weathered many storms over the decades, including a destructive nor’easter after Thanksgiving in 1974, but nothing like Fran.

“I knew when I left, based on the strength of storm, there probably wouldn’t be anything left, but when you see it, it goes through you,” Lore said. “I was intent on rebuilding, so I threw my energy into that instead of wasting my time moaning about what was there. It could be replaced.”

By Aug. 30, 1997, the new pier was completed, just in time for the fall fishing season that turned out to be the best the business had ever experienced. There was help from the state, especially in expediting permits, and federal assistance that allowed the rebuilding, but Lore said the community also came together in the storm’s aftermath.

“Everybody had a positive attitude. Everybody who had been living here for years was united to get things back the way they were,” Lore said. “Losing the pier was like losing a loved one. It was like that with the island. It took quite a beating. It was horrible storm and we caught the worst part of it. As it moved up, we got the bad side of it, where most of the damage was done. It couldn’t have hit us any worse.”

Pender County Sheriff Carson Smith Jr. was in 1996 the county’s emergency management director. Speaking Thursday just before going into a meeting to prepare for the arrival of Tropical Storm Hermine, Smith said Fran left lasting memories of scenes few in the community had ever witnessed.

“The brunt of Fran came at night,” Smith said. “Once the center passed and we could feel the wind shift it was about the same time the sun was coming up. It was evident then that we definitely took a major hit.”

One of the most memorable images Smith recalled was of beach homes washed not only off their foundations but swept completely off the barrier island.

“There was one house pretty much intact sitting between Topsail Island and the mainland,” Smith said.

He said an aerial tour of the storm’s aftermath was also striking.

“On much of the island, you could not see the asphalt. There was sand everywhere. When you looked at it from the air, it looked just like one big beach,” Smith said.

Inland, many trees not toppled during Hurricane Bertha were snapped, and roads were littered with felled trees. Flooding also became a problem as creeks and rivers crested in the days following the storm.

“We had some very high water during Fran,” Smith said, adding that the rising rivers were described as a 100-year flooding event.

After the storm, the county partnered with the U.S. Geological Service to install a flood monitor on the Northeast Cape Fear River. That device proved valuable three years later during Hurricane Floyd, which produced a 500-year flood, Smith said.

Bertha a Wake-up Call

Just weeks before Fran arrived, Hurricane Bertha had come through on July 12. Bertha was the first significant storm to hit the area since Hurricane Diana in 1984. Compared to Fran, Bertha was a lesser, Category 2 storm when it made landfall at Figure Eight Island, about halfway between Topsail Island and Wrightsville Beach, but Bertha caused $135 million in insured damage, mostly on the coast, and was blamed for a dozen deaths.

“Bertha, earlier in the summer, was a bit of a wake-up call,” Barnes said. “Bertha was the first hurricane-force winds that a lot of people here had experienced in their lifetimes.”

On Topsail Island, dozens of homes were damaged or destroyed during Bertha, including 40 homes lost in Surf City. About a quarter of all houses in North Topsail Beach lost roofs and three washed away during Bertha. The police station in North Topsail Beach was destroyed and later temporarily replaced with a double-wide trailer that washed away in the 12-foot storm surge that accompanied Hurricane Fran.

“On Topsail Island, Bertha did a significant amount of damage and then Fran came through and made it that much worse,” Barnes said. “The 12-foot surge, it had been a long time since we had that kind of water affecting a barrier island. In North Topsail Beach, there’s not a lot of high ground, so it was especially vulnerable.”

Fran’s storm tide over-washed nearly all of Topsail Island, and to a much greater extent than seen during Hurricane Bertha, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. The agency says much of the worst coastal damage from a hurricane happens in areas of extensive over-wash. Homes built before the state’s building codes were overhauled in the 1980s – those beach houses not on pilings or on inadequate pilings – fared the worst.

“Many homes that survived were where the over-wash was allowed to flow under the house because it was up on stilts,” Barnes said.

As the floodwater from Fran began to recede, it cut through North Topsail Beach’s New Inlet Road in at least a half-dozen spots, washing away large sections of the roadway and numerous homes along the route. Fran damaged more than 300 homes on the island, with more than 90 percent of buildings in North Topsail Beach damaged beyond repair.

“It was certainly a very hard-hit community,” Barnes said.

Lessons Learned

Stuart Turille is the current town manager of North Topsail Beach. Although he didn’t hold the job back when Hurricane Fran struck the community, he said the town’s preparedness is based on lessons learned during the back-to-back storms 20 years ago.

“The primary thing is our knowledge and experience,” Turille said. “We know – having been through a devastating hurricane – we now know where our vulnerable places are in town.”

Because members of the town staff have lived through past storms, their experience is valuable in restoring order after a storm has passed, Turille said.

“Should we receive a devastating event, we now understand the process and we know how to get back on our feet quickly,” he said.

Back in 1996, North Topsail Beach was still a fairly new town, having incorporated just six years earlier. Staff at the time lacked experience in dealing with bad storms, Turille said, and the one-two punch of Bertha and Fran wiped out major town infrastructure, including the town hall and police station. The facilities in place now were built to withstand stronger winds and rising water, but contingency plans are now in place, just in case.

“We’ve thought through our emergency planning, what we’d do to relocate should town hall be damaged,” Turille said. “We have a backup, we’ll relocate and still be operational.”

Turille said the damage from past storms has also underscored the need for pushing for coastal protection efforts, such as the town’s ongoing beach re-nourishment projects, which have pumped in sand to help broaden the beach and elevate the height of dunes that serve as the front line of protection from coastal storms.

Turille said rebuilding the beach and dunes will help prevent the kind of widespread property losses seen during Fran.

“Some of worst area of swash zones that overran the dunes were in that area,” Turille said. “Now, we’ve just completed a project to broaden the berm and heighten the dunes as coastal protection measures.”

The nearly $17 million project was completed last summer. It sparked controversy when tons of rocks were picked up by the dredge about a half mile offshore and pumped along with the sand onto the beach. The material didn’t meet guidelines for sand quality on re-nourished beaches and the amount of rock that showed up on the beach prompted worries that nesting sea turtles would struggle with the obstructions.

Turille said that with all the attention on the rocks, the public “lost sight of the enhanced protection” that re-nourishment offered, but town officials remained focused.

“That’s why our shoreline protection plan has honed in on how we can get that done, a broadened berm and higher dunes,” he said.

Barnes said beach re-nourishment has proven to help coastal communities withstand strong storms. The benefits have been successfully demonstrated in towns including Wrightsville Beach and Carolina Beach in New Hanover County.

“In that particular location, nourishment worked and saved property,” Barnes said.

Not everyone is sold on beach re-nourishment and artificial dunes as protection, certainly not Orrin Pilkey. The famed geologist is a professor emeritus of Earth and Ocean Sciences at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University and founder and director emeritus of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University. He’s also an old North Topsail Beach nemesis, once calling it the most dangerous developed beach on the East Coast.

“That’s lipstick on a pig. That’s just nonsense in any significant hurricane,” Pilkey said of the beach project. “It’ll be brushed away just like brushing a fly off the counter.”

Pilkey said dunes created by bulldozing sand into piles, a process he described as “a form of beach erosion,” may offer some protection from small storms, but not during a major hurricane such as Fran. It’s especially inadequate on Topsail Island, where the natural elevation is so low and where property owners affected by Fran were allowed to rebuild on the most precarious sites.

“Now North Topsail looks like nothing ever happened, but I and others consider that to be the most dangerous community of the East Coast barrier islands. It’s the least developable, and that’s not hyperbole, I really believe that,” Pilkey said. “Building high-rises on North Topsail was madness. The reason it’s madness, they now have no way to respond to sea-level rise. They can’t move the high-rises back. The loss of a beach cottage is not a disaster, you can move a cottage back or raise them – that helps a little while – but with high-rises, all you can do is abandon them or turn them into fishing reefs.”

The biggest outrage, Pilkey said, is that homes were allowed to be rebuilt on the half-dozen or so spots where floodwater cut channels through the island as it receded to the ocean. Now, those little, temporary inlets feature bridges where the road was washed away and single- and multi-family residences standing between the bridges and the ocean.

“That’s the greatest madness of all,” Pilkey said. “I wonder sometimes whether the people who own the houses were aware of it. I have a suspicion they were not.”

The channels eventually closed via natural coastal processes, but the areas remain vulnerable, as does the road, New River Inlet Road, Pilkey said.

“In certain storms, especially when it floods from the backside, the road will be cut off rather quickly, the escape route will be cut off quickly,” Pilkey said.