The recent resignation of a founding member of the science panel that advises the state’s Coastal Resources Commission leaves an imbalance in expertise, according to some of the panel’s remaining members.

East Carolina University geologist Stan Riggs resigned July 24 in protest over legislative decisions on coastal policy during the past five years, restrictions placed on the member panel’s work and, most recently, the commission chairman’s stated desire to reclassify currently designated inlet hazard areas on the state’s coastal barrier islands.

Supporter Spotlight

“What I see happening is people are not paying attention to what the science panel has done and what’s really happening in our coastal system,” Riggs said in a recent interview. “If we want a viable economy going into the future and help people living out there on the coast, we have to deal with the long term as well as the short term. We’re building infrastructure out there for at least 100 years. Our resources are too important for ignoring the dynamics of that system.”

The panel may have up to 15 members. Five of the nine remaining members of the panel Riggs proposed in 1996 are engineers. Riggs’ departure leaves only three geologists on the panel, William Cleary of the University of North Carolina Wilmington; Stephen Benton, who retired from the North Carolina Division of Coastal Management; and Greg “Rudi” Rudolph of Carteret County’s Shore Protection Office.

“The panel has been continually reorganized around trying to make a match between coastal sedimentary geologists on one hand and coastal engineers on the other hand,” said Charles “Pete” Peterson, a biologist with the University of North Carolina’s Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City and also a member of the panel. “Those two groups have different ways as a whole of looking at things and analyzing things. It’s productive to have both voices, and the panel has the capacity to debate what the different disciplines are saying.”

Peterson named several geologists he’d like to see considered as Riggs’ replacement, including Reide Corbett of UNC’s Coastal Studies Institute, a UNC Wilmington professor and others. “Those people are the kind of strong coastal geologists that our panel is severely underweighted in,” Peterson said.

Corbett said it would be an interesting offer, especially in light of the controversy that has surrounded the panel in recent years, but he would consider it.

Supporter Spotlight

“As frustrating as it is, I still think we need that sort of science on that panel. It’s only going to get worse if no one is there to voice that opinion,” Corbett said of the geologists’ perspective.

Rudolph said he’d also like to see another geologist appointed to the panel but the sometimes controversial nature of the panel’s work could present challenges. “Some don’t like the CRC because it’s more political now,” he said.

Rudolph noted he didn’t believe members of the panel should be involved in choosing Riggs’ replacement.

“I’m not a big fan of the science panel selecting who the future science panel members are going to be because then it’s more like a club,” Rudolph said.

It Started with Sea-Level Rise

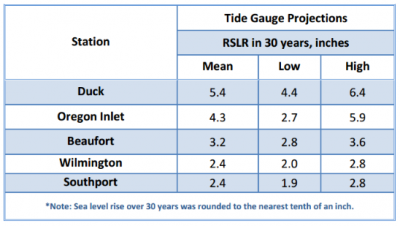

The panel’s work on sea-level rise projections made it a political target and thrust the state into the national spotlight in the arena of climate science. The state General Assembly’s response to the report confounded geologists on the panel.

Riggs said that General Assembly’s reaction to the panel’s original, 2010 sea-level rise report, which forecast up to a 39-inch rise by 2100, was the beginning of the end for him.

“The original sea level report, things were still very healthy and the science panel was working. Things were exciting. We had the support of the division and the CRC,” Riggs said. “The atmosphere changed when Republicans gained control in Raleigh. It was at that point where the legislature rejected our report,” Riggs said.

First there was a bill that didn’t pass that would have “outlawed sea-level rise,” as Riggs put it. The next year, a bill did pass that put constraints on what the state could do with respect to talking about and planning for sea-level rise.

“That was the beginning,” Riggs said. “That’s when it sort of began to deteriorate, in my opinion.”

Riggs said the 2010 sea-level rise report with its outlook to 2100 was used as a model by other coastal states that were behind North Carolina in considering the implications. Here at home, the developers on the coast also began to realize what the report could mean for them and appealed to their representatives in Raleigh to block any rulemaking based on the projections.

“What really got the natives going on that was that the CRC at the time directed its staff that all future construction had to consider that (scenarios looking forward to 2100),” said Rudolph, who studied for his master’s degree at ECU with Riggs as his adviser and who also worked as Riggs’ research assistant. “The policy was the thing that got people all riled up and screaming to the General Assembly.”

Undeterred, the panel continued its work, moving on to study and map inlets in great detail. Panel members put in an “incredible amount of time,” Riggs said.

“The whole problem associated with development on the inlets was coming to a head. We were working on (the inlet project) until the assignment came for the 2015 sea-level rise report. It was basically dictated to us how we had to do that,” Riggs said.

Rob Young, a geologist in charge of the Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines at Western Carolina University, and Antonio Rodriguez, a geologist and geophysicist at the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences, resigned from the panel in 2014. Both cited at the time personal frustrations with the legislative mandates placed upon the panel, including those guiding its work on sea-level rise. Riggs said the dictatorial environment prompted their departures.

“It got too restrictive for them,” he said. “These young, bright scientists that helped write the original report decided for their own reasons why they didn’t want to waste their time anymore.”

The updated report was due March 31, 2015, but was finished well in advance. Once the panel completed its work on the report, it never met again. Riggs said he had grown increasingly frustrated with the process. The international science community had helped with the original report but the panel was not allowed to draw from that expertise for the 2015 update. Also, former members of the panel were not allowed to help.

“They didn’t allow us to do our own science review. They did allow two engineers to review it and they made valuable contributions to the report,” Riggs said, adding that those contributions were no substitute for an open review process, “which is critical for science.”

Riggs said there were also other reasons why he and other geologists resigned. The nature of the panel had changed over the years, Riggs said, from purely a scientific endeavor to one that now includes members that he said may have a vested interest in coastal policy decisions.

“Some (panel members) run major companies that make a lot of money pumping sand and hardening shorelines. I wanted to let people know that it’s not working very well. Everything is not copasetic in the kitchen,” Riggs said.

Panel member Tom Jarrett is an engineer formerly with the Army Corps of Engineers and now with Coastal Planning and Engineering of Wilmington. The firm specializes in beach re-nourishment and inlet-dredging projects.

Jarrett was appointed to the panel in 1997, while still with the Army Corps, and like Riggs is one of the original members.

“I retired from Corps in December 2000 and at that time the CRC didn’t see any reason for me not to continue to serve. They elected to keep me on,” Jarrett said. “Even though I now work for a private consulting outfit I’ve tried to keep my views neutral. As far as any conflict of interest, I’ve been very careful to stay out of that.”

Jarrett said he’s been intimately involved in development of inlet hazard areas, a study in which Riggs was less involved. Jarrett said he took a leadership role in pushing for legislation to allow terminal groins to be built on North Carolina beaches, but that’s where his role ended.

“With terminal groins, I admit to playing a role in getting that going, but once the ball got rolling I didn’t take any role in it,” Jarrett said.

Jarrett also provided comments for the panel’s subsequent report on terminal groins.

“I commented on that but I’ve tried to be as neutral and objective as I possibly could,” Jarrett said. “Nothing I said can be interpreted as having benefited the private sector.”

Jarrett said serving on the panel takes a lot of time and effort, but he plans to continue to serve as long as he’s wanted.

“I’m not getting paid for it,” he said.

Other Remaining Members

In addition to Cleary, Jarrett, Peterson and Rudolph, the remaining members of the panel are Margery Overton, the panel’s chairwoman, of the Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering at North Carolina State University; Spencer Rogers, who has geology and engineering degrees but works as an engineer with North Carolina Sea Grant in Wilmington; William Birkemeier, a retired engineer from the Army Corps of Engineers; and Elizabeth Sciaudone, also of the NCSU’s engineering department.

“Usually our challenge is to find enough engineers. Interestingly that’s not the mismatch at the moment,” Peterson said.

Peterson said the remaining members of the panel are “people who have contributed mightily in their fields and are respected in their fields.” Their philosophical differences lead to interesting debates, he said.

“But I don’t think anybody is going to be pushed around,” Peterson said.

Frank Gorham is chairman of the Coastal Resources Commission and has the responsibility of appointing Riggs’ replacement on the panel. A self-described “big science guy,” Gorham said he strives to get at “real data” on coastal issues.

“I have the greatest respect and appreciate for what Stan did for the state and I’m sorry to lose him,” Gorham said, adding that he was pressured after the sea-level rise report to fire the entire science panel and start from scratch.

“I opted not to do that. I kept Stan Riggs because I respected him,” Gorham said. “We have to plan for a range of cases. Ten geologists in a room will come up with 11 different answers. I am very used to scientists disagreeing and I think that’s healthy.”

Gorham said he wants to wait on making a new appointment until after a set of priorities is established for the panel.

“Once we agree on those, then we go find the expertise,” Gorham said.

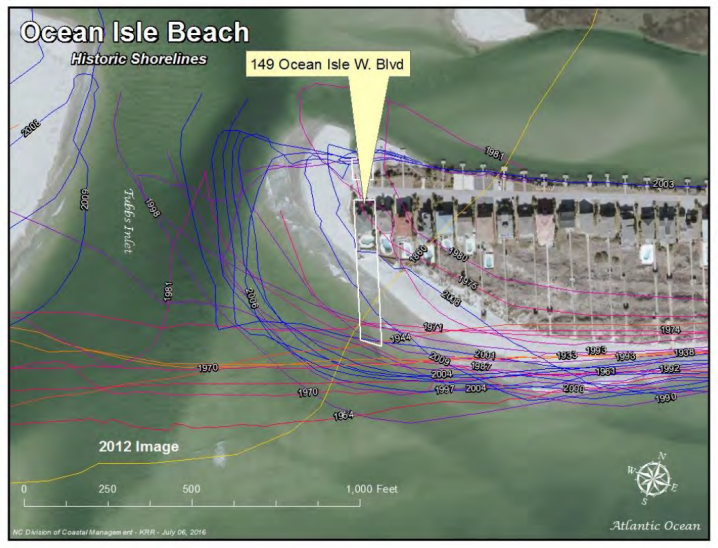

Those priorities could include updating erosion predictions and cycles, particularly in designated inlet hazard areas, which Gorham would like to rename “inlet management areas.”

“Inlets have a greater erosion rates than non-inlet areas, I realize that,” Gorham said. “It’s frustrating when people’s homes get put in an inlet hazard area. If we called it something different than inlet hazard and we got people to recognize the severe erosion rates …”

Gorham interrupted himself, noting that Riggs thought the decision to change the designation meant downplaying the increased rates of erosion.

“It’s more an attempt to get people to pay attention to the study,” Gorham said. “We had people more worried about their property value going down and then they wouldn’t even listen to the data. I live close to an inlet. I know there’s more instability close to inlet. We need to get the science panel to show where an inlet has an impact.”

Gorham said subcategories within the inlet areas may be the best approach, with updated science on erosion rates there, which would likely vary in degrees of severity of erosion.

“We have to factor in man’s willingness to do beach re-nourishment and inlet dredging,” Gorham said. “Man’s desire to keep beaches re-nourished will offset some of the higher erosion rates that are due to an inlet.”

The Final Straw

Riggs said the commission’s recently suggested inlet zone reclassification was the final straw for him. Softening the definition will only encourage irresponsible development, he said.

“You’re building on a sand pile that wasn’t there a few decades ago. That’s crazy. We need to do a better job of managing our resources and protecting people because sea level is changing and it’s going to have a big effect on inlets,” Riggs said.

His protégé, Rudolph, however says taking a new look at inlet hazard zones is acceptable as a means of evaluating future risks, as long as the panel ignores the policy implications.

“If the CRC wants to do the setbacks differently in inlet hazard areas, compared to oceanfront, that’s totally their decision,” Rudolph said. “If the CRC’s concern is that you have inlet hazard areas and it connotes bad things and maybe that’s not what the connotation needs to be, then that’s really up to them. Most of the inlets are pretty much developed already. Changing the policy is going to be difficult because you already have a bunch of structures there, but we need to look at preventing more inlet-ward development. Setbacks moving seaward on the oceanfront may be OK, but on inlets it’s a whole different process. They wouldn’t have us looking at it if they weren’t thinking about doing something different with it.”

The Heart of the Group

While Riggs wasn’t the first geologist to step down in frustration, his departure is perhaps the greatest loss to the panel, Peterson said.

“Losing Stan is kind of like losing the heart of the group,” Peterson said. “His seminal role in getting this established – he was the first person they thought of to help formulate the group to speak to the many choices we have in response to challenges in our coastal zone. His loss will be felt in every meeting and every hour that the panel does its work.”

Riggs, 78, said he plans to spend his remaining years finishing up books he’s been writing that deal with the dynamics of coastal systems. As a lifelong educator, he sees it as a higher calling.

“I can do far better working toward educating the public than I can fighting the legislature. It takes an educated public to get a good legislature,” Riggs said. “The decision was, what are you going to do with the rest of your life? I’m not going to piss away any more time. I’m not an angry person who is out to get anybody, I’m just trying to see that we take better care of the coast.”