ELIZABETH CITY — Blue catfish grow fast and grow big – and they taste good. But the greedy interloper could become an ecosystem nightmare in North Carolina if a recent regulatory change is not reversed.

The voracious apex predator has made its way down the Chesapeake Bay into the Chowan River and Lake Gaston, where three of the fish caught in the last six months each exceeded 100 pounds. Fishermen and scientists have reported seeing increasing numbers of bycatch of the blue catfish in crab pots and nets.

Supporter Spotlight

“It seems like here in recent years, the population levels have reached a tipping point,” said Charlton Godwin, fisheries biologist with the state Division of Marine Fisheries.

Godwin said the number of blue catfish, one of the largest of the eight or so native catfish species in the U.S., has increased notably in the western Albemarle Sound and its tributaries, and the mature fish pretty much eat whatever they want. “I’ve seen striped bass up to 22 inches in the stomach of a blue catfish,” he said.

Fortunately, blue catfish make delicious eating, and a robust commercial fishery is keeping the invasive species from wiping out populations of native fish, such as river herring, blue crab, largemouth bass and striped bass. But a rule inserted in May in the federal Farm Bill could potentially kill the commercial market, and in turn leave long-living blue catfish free to proliferate, unfettered, in the state’s sounds and rivers.

“Economically, it’s a huge issue for North Carolina,” said Jerry Schill, president of the North Carolina Fisheries Association, a commercial fishing advocacy group.

Despite criticism from the federal Government Accounting Office that said it would be duplicative and costly, the U.S. Senate in May added a program to the 2008 Farm Bill that changed the responsibility for inspection of catfish from the Food and Drug Administration to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, according to a letter to the leadership of the U.S. House of Representatives signed by 200 House members. The FDA regulates fish, while the USDA regulates beef, poultry and pork.

Supporter Spotlight

In the letter, members call for a bipartisan joint resolution of disapproval, a procedural action intended to end the USDA catfish inspection program and leave it under the FDA’s jurisdiction.

Mississippi Republican U.S. Sen. Thad Cochran is behind the new program, which provides inspection for farm-raised catfish coming from China and Vietnam, competitors with Mississippi catfish farms. According to supporters of the regulatory shift, the imported Asian catfish are often tainted with toxic chemicals and require thorough inspection by USDA. The Catfish Farmers of America, a Mississippi-based trade group, said the USDA program would provide a “greater level of protection for American consumers” than the FDA inspection.

Critics contend the move was intended to make it more difficult to import catfish without doing anything to make imports safer.

But, paradoxically, U.S. wild-caught catfish have been caught in the same regulatory net. Other bycatch are U.S. fishermen and seafood processors, who would be forced to do costly upgrades to their plants to meet the new standards required by the USDA. At the same time, the program will cost millions more to run, and will result in higher prices for consumers.

“The facts are clear,” said U.S. Rep. Vicky Hartzler, R-Mo., in a press release dated July 7. “The taxpayers have been put on the hook for an unnecessary and wasteful program that was dropped in the Farm Bill Conference Report at the last minute, without a vote, to protect special interests.”

According to the Fisheries Association, USDA inspection will have a negative impact on wild-caught catfish and the related jobs and small businesses the fishery supports in the domestic commercial fishing industry

“It’s just boggling my mind as far as the complexity of this issue,” Schill said.

Blue catfish has developed into a significant commercial fishery in the northeast, but unless the USDA inspection is reversed, there are doubts whether it will survive.

“We’ve been processing catfish for 50 years, and never had a problem,” said Ricky Nixon, an owner of Murray L. Nixon Fishery in Edenton.

Nixon said he has until September 2017 to make changes required by the USDA, which would essentially require building a new plant – not a feasible option.

“If you take Murray Nixon out of the equation, with how much we handle – these fish are eating up everything – it’s going to be a problem,” he said. “We’re the only catfish processor in northeastern North Carolina.”

It would also create a domino effect, he said. At least half of his 48 employees would be laid off. And fishermen would stop fishing catfish because there’s no place to sell it.

Nixon said 2.5 million pounds of blue catfish, most weighing 3 to 8 pounds, were caught last year, selling for 30 cents to 70 cents a pound.

“That’s good money,” he said.

Not only does the successful remedy to “blue cat” overpopulation – eating them – benefit the fishing community and the consumer, it could help keep a balance in the ecosystem.

“Our concern is, if the population of blue catfish keeps rising,” said Corrin Flora, marine fisheries biologist with the state Division of Marine Fisheries in Elizabeth City, “it’s going to eat our native fish species.”

Willy Phillips, owner of Full Circle Crab Co. in the Tyrell County town of Columbia, said that hundreds of pounds of blue catfish were found during a few months over the winter in crab pots near Oregon Inlet and the Alligator River – a first for the area.

“They were everywhere,” he said. “That was a spike that really caught everybody’s attention. That was just amazingly different – the sheer volume.”

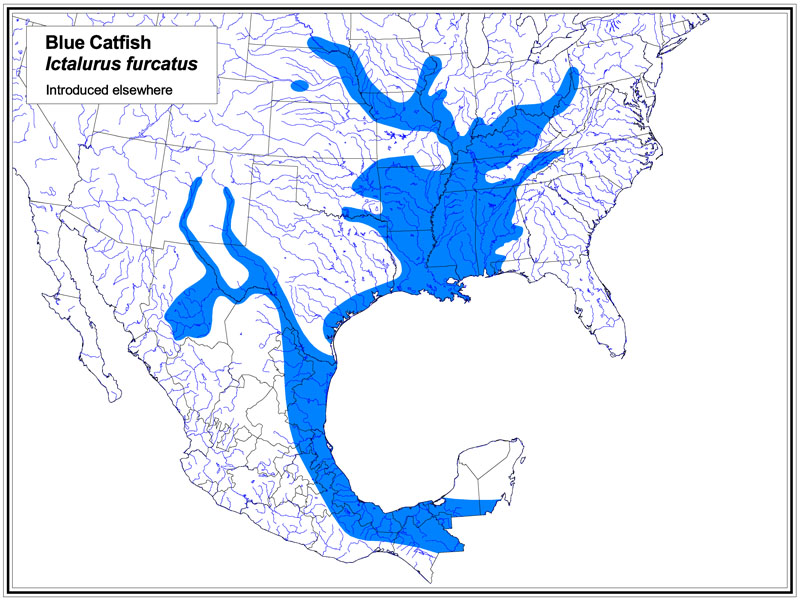

A native of the Mississippi river basin, blue cats – yes, they’re blue and have whiskers – were introduced into the tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay in the 1970s as a recreational fish, said Bill Goldsborough, fisheries director for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

But similar to other non-native species – such as lionfish and kudzu – they’ve become invasive, he said. In a recent survey of the James River, for instance, blue catfish composed more than 70 percent of the biomass, he said, although it appears that their population is leveling off.

Blue cats can grow up to 140 pounds and 4.5 feet long – twice the size of any native Chesapeake catfish.

Biologists are not sure what impact blue catfish has had on populations of other fish species, Goldsborough said, but it is known that they’ve eaten more than their fair share of shad, herring, blue crabs and menhaden.

One of the management tactics recommended by the Invasive Catfish Task Force established in 2012 by Chesapeake Bay fisheries managers was creating incentives to build a commercial fishery. A 2014 draft task force report warned that action was required to prevent “irreversible” damage in the Chesapeake.

Agencies in Virginia and Maryland, alarmed by the expanding range and population of blue cats, have put considerable resources into research and education of the fishing community, Goldsborough said. For instance, some fishermen have released blue cats into new water bodies as a way to establish them for recreational fishing, without realizing that the big fish will take over other species.

Goldsborough said that if North Carolina wants to get ahead of the blue catfish menace, the state should encourage people to catch them and not throw any back. It would also be a good idea, he added, to put regulations in place against keeping live catfish with the intention of spreading them around.

Flora, with Marine Fisheries, said that there are already “a lot” of blue catfish in Lake Gaston, where Landon Evans, 15, of Benson, last month caught a state record 117-pound, 8-ounce blue cat. The fish have so far been found only in waterways bordering southeastern Virginia, she said, but the extent of their range remains unclear. The species has also been documented in the Neuse, Tar and Cape Fear rivers.

The division regularly monitors waterways with gill net and trawl surveys, Flora said, and is keeping a close eye on blue catfish.

“We realize there is a concern in the area,” she said.

The House left town this month without taking a vote, said Joshua Bowlen, chief of staff for Rep. Walter B. Jones, R-N.C., who signed Hartzler’s letter.

“My take is if they haven’t moved it yet, there’s a problem,” Bowlen said. “There’s something that the leadership sees that’s caused them not to move this thing yet.”

The matter will likely be brought up again after lawmakers return to work in September, he said.