First of two parts

Thousands of species have been listed as endangered or threatened in the more than 40 years since Congress passed the Endangered Species Act. In fewer than half the cases, though, federal authorities have failed to take the next essential step required by the law of protecting the habitat that these plants and animals on the brink of oblivion need to survive and recover.

Supporter Spotlight

We’ll spend the next two days exploring this issue of critical habitats – what they are, why they’re important and why federal authorities have to be forced to do what the law says they must.

Currently, more than 1,500 species are listed under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. As of January, though, critical habitat has been designated for 704 listed species, according to the latest figures from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the primary agency that administers the law.

There’s no one simple explanation for the lag. Officials in the agencies responsible for determining critical habitat blame funding and staff constraints for the backlog. Environmentalists and some academics say that politics also play a big part in missed deadlines because critical habitat designations are usually seen as threats to commerce and development.

Establishing critical habitat has, to a degree, become a Groundhog Day-like process with environmentalists routinely filing lawsuits to prompt government agencies to act in accordance with the law.

As things play out in the courts of law, industry, local government officials, developers and private property owners debate what effects critical habitat designations may have on their businesses, livelihoods and their ways of life.

Supporter Spotlight

What Is It?

Under the law, the Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service must decide whether a listed species has critical habitat. If such a determination is made, those agencies must identify and map those areas.

The Fish and Wildlife Service covers listed species on land. The fisheries agency is responsible for designating critical habitat for listed species in water.

Critical habitat, as defined in the law, is a specific geographic area that contains features essential for the conservation of a threatened or endangered species and that may require special management and protection. It may include land or water that is not currently occupied by the species but that will be needed for its recovery. The agencies publish the draft boundaries of proposed federal regulations in the Federal Register. Final boundaries are published after the agencies receive and consider public comments on the proposal.

Congress in 1978 added to the Endangered Species Act a provision requiring that critical habitat designations coincide with a new listing. As the agencies prepare to map critical habitat boundaries, they must consider economic effects to that area.

Areas may be excluded from critical habitat designations if the effects on the economy or on national security outweigh the benefits of selecting an area.

There are other exceptions to the critical habitat designation rule. The agencies will not map out areas for listed species that are a high commodity to poachers, a move that would only make it easier to track down a species.

If additional studies and data are needed to determine a designation, the agencies get up to one year to make a determination.

“That is not recommended, but it is allowed,” said Brett Hartl, endangered species policy director for the Center for Biological Diversity. “Over the last five or so years (the Fish and Wildlife Service) have generally gotten out a vast majority of designations within that one-year window.”

The Tucson, Arizona-based center is a nonprofit organization focused on saving imperiled species. The center has made a name for itself filing lawsuits over the Endangered Species Act, winning cases that have resulted in the listing of more than 300 species and protecting more than 120 million acres of habitat.

What Does It Do?

Internal opposition within the halls of Washington is partly to blame for missed deadlines, Hartl said.

“There’s a perception that critical habitat grinds everything to a halt, but that’s not really true,” he said.

Critical habitat does not create a refuge or sanctuary for a species. It applies only to federal projects, federally funded activities and federally permitted activities.

Examples for such activities in North Carolina coastal areas include dredging, beach nourishment, construction of terminal groins and development where a builder must obtain a permit from the Army Corps of Engineers.

Before issuing a permit for such projects, the Corps must conduct a “Section 7” review, which is named after the section of the Endangered Species Act that requires federal agencies to determine whether permitted projects will adversely affect the habitat listed animals and plants need to survive and recover a species.

The Fish and Wildlife Service determines whether a proposed project may prevent the recovery of any listed species.

Critical habitat designations are another tool the federal agencies use to ensure that a project will not have a significant adverse effect on a species.

“The critical habitat designation really allows us to focus our recovery efforts,” said Ann Marie Lauritsen, the Fish and Wildlife Service’s southeast sea turtle recovery coordinator. “For loggerheads, it doesn’t differ from what we’ve been doing all along. We have been looking at the nesting beach already, so it comes hand-in-hand.”

Turtle Habitats

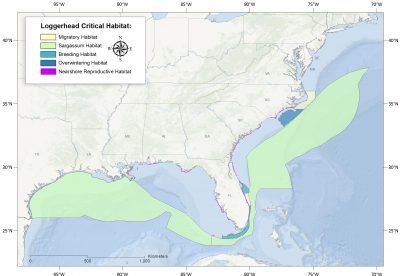

Loggerheads were originally listed as “threatened” worldwide in 1978, and their status was raised to “endangered” in 2007. That should have triggered a critical habitat designation but it took seven years for the agencies to make that determination and only after three groups, including the Center for Biological Diversity, sued them.

The agencies had exceeded the deadline to establish critical habitat for loggerheads, but, according to Lauritsen, the Fish and Wildlife Service was actively working on the proposed designation at the time it was petitioned.

“It was not a matter of that we were waiting,” she said. “We were in the process and it was a complicated process.”

The agencies announced in July 2014 two final rules designating 88 nesting beaches stretching an estimated 1,500 miles in coastal counties from North Carolina to Florida, Alabama and Mississippi.

The Fish and Wildlife Service is currently reviewing critical habitat for green turtles, which were also listed in 1978 as a whole population. The agency has since determined that there are 11 distinct green turtle population, Lauritsen said.

Green turtles are listed as threated in North Carolina. The Fish and Wildlife Service is still gathering information on potential critical habitat for the species in the state.

“It’s not clear yet as a foregone conclusion whether North Carolina will have critical habitat or not,” Lauritsen said. “Green turtle nesting in North Carolina is much, much lower than loggerheads.”

Sixty-two animals and plants in North Carolina are protected under the federal law. The agencies have designated critical habitats for 32 of those species. Plants make up the biggest category of protected species with 27 on the list. Interestingly, none has had habitats protected.

Major Backlog

Officials with the two agencies told a congressional committee in a 1992 that they had designated critical habitat “to the protection of less than 20 percent of the species that have been listed.”

They said that designating critical habitat was considered a low priority because the designations “do not necessarily provide much benefit to a species.” Getting the biological and economic information necessary to make sound decisions could be difficult to obtain, they also noted. Publishing the maps of the areas, they cautioned, may expose species to collection or illegal taking.

While the agencies have gotten better in meeting the critical habitat deadlines, money and the time it takes to study a species are still issues.

“I would say the pace of listing and the backlog has not gotten better with time,” said Ryke Longest, a professor at Duke University’s School of Law and the Nicholas School of the Environment. “There’s some areas and some whole categories of species that will likely go extinct before the agency gets a chance to study them. Frankly, there’s just never been enough money given for Fish and Wildlife to do the job.”

The Endangered Species Act has been successful in two major areas, he said. The law has greatly reduced criminal trade of items such as tusks and animal hides. The act has also helped mitigate the impacts of federal activities on listed species.

“It does allow the public and it allows the government decision makers to look at all the impacts of the project,” Longest said.

Politicians looking out for special interest groups aren’t helping, he said.

“If anything, it’s gotten worse,” he said. “The authors who wrote the Endangered Species Act really meant to try and reverse the extent of endangered species. It’s not at all living up to the promises of its authors.”

The Endangered Species Act is supposed to affect human behavior, Longest said.

“People don’t want to be told that, I understand that,” he said.

But people need to recognize that protecting listed species goes hand in hand with human quality-of-life issues, such as clean water, Longest said.

Take the Tar River spinymussel. This tiny bivalve is one of only three freshwater mussels with spines in the world and it is found solely in the Tar and Neuse river systems.

The species was listed as endangered in 1985. Neither the state nor local governments with jurisdictions where the mussels live has regulations or ordinances adequate to protect the species from impacts of pollution sources from agriculture, private forestry and development.

“The Clean Water Act has already told us we want to fix that,” Longest said. “People in polls say they want clean water, so why are they resisting this? The listing process is not just about protecting species; it’s raising the alarm about human threat.”

To Learn More

- The Endangered Species Act

- Critical habitats

- Endangered species in North Carolina

- Critical habitat designations in North Carolina

- Center for Biological Diversity

Wednesday: What critical habitats do and don’t do