Second of three parts

NAVASSA – Creosote was one of numerous toxic materials handled at the various industries that have operated here over the decades. Industry brought needed jobs, but in many cases contamination remained after the factories closed.

Supporter Spotlight

Veronica Carter serves on the North Carolina Coastal Federation’s board of directors and as the federation’s representative on the Southeastern North Carolina Environmental Justice Coalition. She said the number of contamination sites in and around Navassa is “mind boggling” considering the size of the community, which covers 14 square miles and includes about 1,500 residents.

“If you’re talking environmental justice, these guys are like the poster child because the demographics of the county are probably like 85 percent white and the rest minorities. Navassa is the flipside of that,” Carter said.

Navassa is quiet and rural, seemingly much farther removed from the urban bustle of nearby Wilmington, but a new highway under construction could soon bring big changes. There is a steady flow of big trucks in and out of town because of the highway construction and local industry that remains. A major rail yard here provides a vital connection for the state port in Wilmington and the state’s interior, but the town sees little economic benefit from it.

Neither does the town benefit much from the wealth and recent growth of the surrounding area. There are no golf courses here, although there are about 30 elsewhere in Brunswick County. There is no neighborhood of waterfront “McMansions,” as may be found along the Intracoastal Waterway and at the Brunswick Island beaches just a few miles south. What might have been prime real estate with scenic river views has remained undeveloped for more than 40 years because of the creosote contamination at the 251-acre Kerr-McGee Chemical Corp. site. Contamination has already been addressed and some commercial redevelopment has occurred at other sites around Navassa, but the Great Recession hit hard here and efforts to lure new investment since then have yielded little benefits.

Railroads and Fertilizer

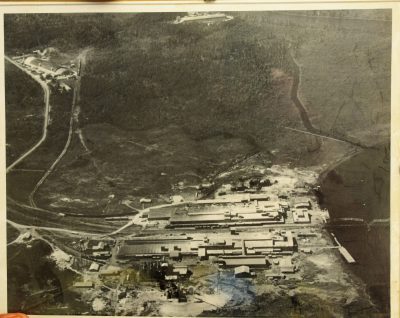

Because of its prime location with rail and river access and proximity to downtown Wilmington, five miles east, the village was home to various chemical, meat-packing and petroleum operations. As many as four now-defunct fertilizer companies employed more than 4,000 workers at one time.

Supporter Spotlight

“Here I am growing up in the ’60s and we’ve got all these fertilizer plants, and even though we’re small and everything, I still grew up in an industrial economy,” said Mayor Eulis Willis. “It’s so much different from the agricultural, agrarian background that most of Brunswick County has had.”

The town was incorporated in 1977 and includes CSX Transportation’s Davis Yard, the regional base for the railroad’s switching operations. Three miles long with a railcar capacity of 2,250, Davis Yard has 55 separate tracks, loading and unloading facilities and warehouses. It connects the Port of Wilmington by rail to points to the west and southwest.

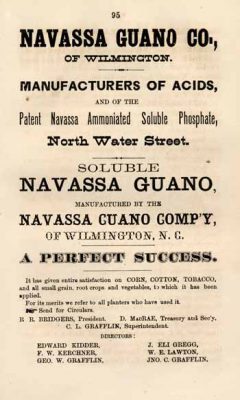

The U.S. Postal Service named the village much earlier, in 1885, after the Navassa Guano Co., a fertilizer factory that opened here in 1869. The factory was built on a site known as Meares’ Bluff, near where the railroad bridge across the Brunswick River had been built two years earlier.

Navassa Guano Fertilizer Co. was formed after large guano deposits were discovered in 1856 on Navassa Island, a small, uninhabited island about 15 miles off the coast of Jamaica. A group of Wilmington investors arranged to have ships that delivered North Carolina turpentine products to the West Indies return with guano from Navassa Island. The fertilizer manufactured here, including phosphate-based product beginning in 1884, was then transported by rail to the state’s interior.

More fertilizer companies followed. Armour Fertilizer Works built a plant here in 1919. Royster Fertilizer came in 1927 and finally Smith-Douglas Fertilizer in 1946. Newspapers across the region, including the Raeford News-Journal and the Lumberton Robesonian, reported the Smith-Douglas plant opening at the time.

“The Smith-Douglass plant at Navassa will add materially to an industry that has long been famous at that location,” according to the reports.

The Cleanup Begins

Navassa Guano Co. sold its property to Virginia Chemical Co. in 1927 and the operation was eventually taken over by Estech General Chemical Co. Mobil Oil Corp. eventually took over the plant assets. Another merger in 1999 created ExxonMobil, which negotiated with EPA officials in 2005 to clean up the site where the agency had found elevated levels of arsenic and lead in soil, groundwater and marsh sediment. ExxonMobil spent $10 million on the project in 2006 and continues to monitor groundwater there.

The EPA began in 2013 cleaning up a former waste oil-recycling plant that operated here from 1993 until 2013. High concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, and heavy metals were found at the P&W Waste Oil Services Inc. site. Company owner Benjamin Franklin Pass of Leland was sentenced in 2014 to 42 months in prison and ordered to pay $21.4 million in restitution for clean-up costs associated with the “widespread” environmental contamination that resulted from mishandling of used oil contaminated with PCBs, according to the U.S. Justice Department.

“Right now, we’ve got three Superfunds and two of them have been cleaned up,” Willis said. “P&W Oil has been cleaned up, the Navassa plant was cleaned up and now we’re working on Kerr-McGee. Now, we haven’t even talked about the little brownfield sites that are involved.”

There’s also the former site of another creosote operation, Carolina Creosoting Corp. on Navassa Road. Other sites of concern include the Royster Fertilizer site off Royster Road and the Smith-Douglas site on Cedar Hill Road.

Also, about 600 workers from Brunswick and surrounding counties lost their jobs in 2013 when the DAK Americas, formerly Dupont, plant near Navassa closed. The plant made polymer resin, polyester fiber and raw materials for resins and fibers. Willis said the shuttered plant could pose additional environmental threats to the community.

Not in Navassa but also nearby are the coal-ash ponds at the Duke Energy Sutton Steam Plant just across the river.

A Company Town

Back in the 1920s and ’30s, much of the land in Navassa was subdivided into small lots for homes, similar to those seen in mill towns.

“That’s all it was, just a little industrial, company town. That was the kind of environment I grew up in,” Willis said.

Louis “Bobby” Brown, 85, of Navassa, worked at the creosote operation for a few years in the early 1950s. He said the work was hot and nasty but job opportunities in Navassa at that time were limited. There were basically only two employers in Navassa and the creosote job paid better, about 75 cents an hour, Brown recalled.

“There wasn’t nothing else out here. You could go to the creosote plant or the sawmill and the sawmill didn’t pay as well,” Brown said.

Johnnie Willis, 88, another surviving worker at the creosote operation, said the wages were lower, about 25-35 cents an hour. Brown didn’t disagree. “Seventy-five or 25 or 35 cents an hour, it wasn’t near a dollar, I know that,” Brown said.

Other workers, including those who unloaded crossties from boxcars, were paid piecemeal, about 5 cents per tie, which often worked out well for hard workers.

“They used to make more money than I did,” Brown said.

The two sides of the creosote production line were delineated by color. Logs peeled of their bark and yet to be treated with the tarry preservative were stored on what was considered the “white side” of the production, while the treatment process and the subsequent handling of treated logs were on the “black side.”

“I worked on the white side,” Brown said.

The differences in black and white also applied to the wages paid. Supervisors at the creosote plant, nearly always white men, were paid more, Brown said. Racial inequality was part of life here.

“A black man couldn’t even buy a Coke,” Brown said. “The only store in town would only sell Pepsi or Nehi to blacks, Cokes were only for whites. I used to say all the time if I had the power of the Lord, I’d make all white people be black for 24 hours and make all black people be white for 24 hours, just so they could see how it felt.”

Few Resources

Mayor Willis said the efforts to get contaminated sites around town cleaned up have been successful only through perseverance.

Willis appealed for years to get the EPA to clean up the Estech site and also contamination found at the Cape Fear Meat Packing Co. site, near where the I-140 bypass is under construction north of town.

“For us living with the environmental issues that we’ve got, there’s not a hell of a lot of resources to address them. And when I start reaching out and asking for help, there ain’t a whole lot of help coming,” Willis said.

Part of the problem is the state’s tier system of scoring for economic assistance, which is based on per capita income, and the relative affluence in communities nearby.

The N.C. Department of Commerce annually ranks the state’s 100 counties based on economic well-being and assigns each a tier designation. Tiers are calculated according to counties’ average unemployment rate, median household income, percentage growth in population and adjusted property tax base per capita.

The 40 most distressed counties are designated as Tier 1, the next 40 as Tier 2 and the 20 least distressed as Tier 3. This system is used by various state programs to encourage economic activity in the less prosperous areas of the state, but Willis is among those who say the method is flawed.

“The two (most economically sound counties) in the whole area are Brunswick and New Hanover, but we rank with Bladen and Columbus (counties) at the bottom, if you look at the per capita income in Navassa,” Willis said. “Every time I go to try and get some help or some assistance, I hear, ‘No, you’re from a rich area.’”

The median income for a family in Navassa in 2010 was $35,179. For Brunswick County, the median income for a family was $42,037. For New Hanover County, the median income for a family was $50,861.

According to the 2010 census, the town’s racial makeup was about 27 percent white and nearly 64 percent African-American. More than 27 percent of Navassa’s population live below the poverty line, with a Navassa’s population was about 1,500 at the time of the 2010 census. That’s compared to 479 in 2000. The huge growth was mainly because residential areas surrounding the town, communities called Old Mill, Phoenix and Cedar Hill, were annexed during the decade.

“Immediately after that, we were tagged in North Carolina as one of the fastest-growing communities, but it wasn’t really the case because of annexation,” Willis said.

It also took a fight to get the state Department of Transportation to add interchanges linking Navassa to the I-140 bypass under construction. Interchanges weren’t included in the original plan, but Willis, a member of the transportation-planning group for the area, protested the decision, citing a case where the DOT put a road through a black community without consideration for the community. It was an environmental justice precedent for highway construction, Willis said.

“The federal government says that if you spend any of our money, from now on, you will make sure that the minority community, if its adversely impacted, that they’ll have a way to get out,” Willis said. “I started emailing everyone that would listen and the next thing you know we got two interchanges in Navassa.”

The ongoing highway project has displaced some of the town’s few white residents.

“We had a nice little enclave of people, 35 or 40 whites, right along where the interchange is going,” Willis said. “Well, DOT came in and bought them all out.”

A few of the displaced families stayed in town but most moved away, Willis said.

‘A good position for growth’

The bypass, and its interchanges are expected to ease access. Willis and other town officials say the new highway will bring needed economic opportunity. Officials began planning years ago for the changes.

“The town is in a good position for growth due, in large part, to the availability of relatively inexpensive land that is undeveloped,” according to Navassa’s 20-year future land-use plan adopted in 2012.

The town’s “gateway plan” includes two, already approved planned-unit developments in the vicinity of the interchanges that are permitted to add a combined 5,500 residential units over the next 20 years, as long as there is adequate water and sewer capacity.

The plan also calls for preserving Navassa’s Gullah-Geechee heritage. This heritage is reflected in the current population of Navassa who are descendants of slaves who worked the rice plantations of the Cape Fear River area.

Trustees of the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation earlier this year awarded the town and the North Carolina Coastal Land Trust a $25,000 grant to develop plans to conserve Gullah-Geechee heritage. The money is to go to produce concept plans for a state Gullah-Geechee cultural heritage center and to protect lands related to Gullah-Geechee history near the town.

While some residents of Navassa have a direct link to the culture, Willis said the concept is a relatively new understanding among townsfolk. It’s important, he said, to help the town establish its own identity.

This identity is also part of the reason for the annual Navassa Homecoming Parade, which was held Saturday. The celebration has been a tradition since 1982.

Despite these efforts, the mayor says his town’s identity is threatened. There’s been talk in recent years of a consolidation of the town governments of Navassa, Leland and Bellville. This would destroy Navassa’s identity, Willis said.

Another issue, Willis said, is that 60 percent of Navassa residents have a Leland mailing address because of the way the U.S. Postal Service routes mail.

“There’s the identity thing there,” Willis said.

To Learn More

- Navassa Island

- Navassa Guano Co.

- Environmental justice in America

- Gullah-Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor

Thursday: The clean-up plan

Part I: “A century of contamination.”