SWAN QUARTER – Some bird lovers and local landowners worry that an unusual agreement signed last month by federal and state wildlife agencies to co-manage Mattamuskeet National Wildlife Refuge in Hyde County could lead to higher water levels in the state’s largest natural lake, driving away flocks of migrating waterfowl and flooding adjacent farmland.

The present could be the future, they warn, after record rainfall over the last several months inundated Lake Mattamuskeet, reducing the number of wintering birds and turning yards into wading pools.

Supporter Spotlight

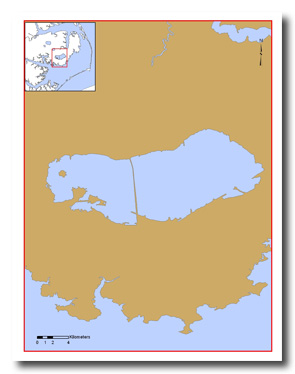

“It’s just a preview of what’s going to happen if they raise the water levels,” said Kelly Davis, a timberland owner and farmer who lives adjacent to the 18-mile-long, seven-mile-wide lake. “The problem is not the water depth; it’s water quality.”

Officials with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which manages the refuge, and the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission countered that the agreement that they signed Feb. 11 is merely an extension of one signed two years ago to help the ailing lake. There are no plans, they said, to raise water levels to make it more conducive to fishing, as some fear. The refuge was created to preserve waterfowl habitat, the officials noted. Nothing will be done to change that, they said.

It’s All About Water

Management of water levels in the lake has been the subject of much debate and controversy in the last several years, with refuge critics demanding that the lake be held high in the summer to improve habitat conditions for now-depleted waterfowl and largemouth bass.

But Davis and other opponents of such a plan said that the necessity of closing structures called flap gates in the 40,000-acre lake would hinder fish and crab migration, drown shoreline marshes and trap harmful nutrients and phytoplankton in the lake.

“If you have gates that don’t open,” said Davis, a former refuge biologist, “it’s like a toilet that doesn’t flush.”

Supporter Spotlight

The currently rain-swollen lake also shows the downside of high water levels in a wind-driven system. “It sounds good to hold the lake at a certain level,” she said, “but you can’t get rid of excess water when you want to.”

For the most part, the refuge allows the shallow lake, which is typically about two feet deep, to naturally rise and fall during the year. The new agreement includes a recommendation to collaborate on biological and legal analysis of current and alternate water management of the lake. But the most striking change is that the document lays out strategies for the state agency to co-manage the national wildlife refuge, a nearly unheard-of bureaucratic blend.

“We’ve looked and we haven’t been able to find anything ceding the management of a resource on a refuge,” said Derb Carter, North Carolina director of the Southern Environmental Law Center in Chapel Hill.

“The real conflict in this is the incompatibility of what the commission wants to see – fisheries management,” he said. “They want to turn the lake into a fishing lake.”

Carter said the purpose of the refuge, which was approved by Congress in 1934, is to manage habitat to the benefit of migrating waterfowl, including thousands of tundra swans, Canada geese, snow geese, pintails and mallards. The lake also attracts bald eagles and ospreys. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, he noted, is obligated to ensure any use of the refuge is compatible with that purpose. The refuge’s long-term management is described in its Comprehensive Conservation Plan, or CCP.

Under federal refuge policy, a compatibility determination is not required for water-level management in a refuge, Carter said. But he added there appears to be additional requirements for review by the refuge manager that have not been met, although he declined to say whether legal action is planned.

“I fully expect there’s more to come,” Carter said.

Birds, Fish and Crops

Higher water levels would shade the underwater plants that the ducks, geese and swan come to the lake each winter to feed on. With less food in Mattamuskeet, the birds will stop coming or settle in nearby private lakes where they could be legally hunted.

In a 2014 report by the Wildlife Resources Commission on sportfish populations and active management of lake levels at Mattamuskeet, it was recommended that lake levels be held 2.1 feet above sensors on the east side and 2.3 feet on the west side as measured by gauging stations, equating to about 48 inches and 60 inches, respectively.

“This recommendation … is based on environmental enhancements that should improve the quality and quantity of fisheries habitats in the main lake,” Mallory Martin, chief deputy director of the commission wrote in 2014 to Calvin Davis, Kelly’s husband. “To benefit fisheries habitats, this water level should be maintained throughout fish spawning and rearing seasons.”

Martin added that the commission was working closely with Fish and Wildlife to “determine the feasibility of implementing this recommendation.”

But Kelly Davis said the commission did not consult with farmers and other landowners about the effects on property surrounding the lake if the levels were held high. Calvin Davis’ family has owned adjacent land since the mid-1700s.

“It’s a beautiful system now, where landowners, waterfowl and fish benefit from the same passive system,” she said.

The westerly wind during the growing season naturally flushes and drains water in the lake, Davis explained.

Recent record rainfall has hindered the operation of drainage gates in the lake, and water is standing deep everywhere.

James “Boo-Boo” Topping has lived on the same land near the lake in New Holland since 1985. For the last two years, he and his neighbors’ land has been inundated with water that often moves from front to back yards, depending on the direction of the wind.

“I have 12-15 inches of water in my backyard, and that don’t make no sense,” said Topping. “I love the refuge, but they need to come up with some way to keep this water down … If they’re going to maintain the lake higher, they need to figure out a way to get the water out.”

No Water Plans

Gordon Myers, director of the state wildlife agency, said that the new agreement is a “natural extension” of one the two agencies signed in 2014. “The Wildlife Commission has no interest in taking over the refuge,” Myers said.

Federal and state wildlife officials, he explained, first met in early November to discuss how to move forward in expanding the relationship to “optimize resources toward the betterment” of the lake.

The co-management agreement, Myers said, allows the partnership to better evaluate the cost and needs of maintaining the lake for waterfowl and fish habitat and as a recreational haven for birders, fishers and hunters.

“It’s really a matter of who, what, when and how,” he said. “It gives more structure. It makes it much more seamless in all directions in our organization.”

The fisheries report and a creel survey provide guidance to the commission, but Myers said whatever action the commission takes must be consistent with and supportive of the refuge’s conservation plan.

“What we believe needs to happen is a fundamental understanding of this ecosystem,” he said.

That entails working with the refuge to study the inflow and outflow patterns of the lake and what factors have contributed to the lake’s deterioration.

More than $200,000 in research is underway right now, Myers said, with a focus on water-quality issues, “to understand the cause and effect so we can address the problem.”

A Litany of Woes

In recent years, the lake has been plagued by numerous, challenging and persistent problems. An invasive carp devours aquatic plants and creates turbidity. An invasive plant, phragmites, crowds out good plants. Algae blooms, including those that harbor toxins, have increased, and fish and waterfowl populations have been steadily decreasing.

Sea-level rise and climate change are contributing factors, but not enough research has been done to provide the science to understand the extent of those effects.

David Viker, refuge chief at the Fish and Wildlife Service’s regional office in Atlanta, said that the goal of co-managing with the state is tap into more resources and work together on a closer basis. The refuge is not giving up its authority to the state, or even planning to raise the water levels, he said.

Viker said that even if the refuge wanted to raise water levels, the federal agency would have to first do an environmental assessment. Even more difficult, it would have to address the 1934 consent decree that forbids the refuge from doing anything to stem the flow of drainage from the farmlands.

State officials understand the legal requirements, he said. “They wanted to make sure if they’re committing staff and dollars, that is more appropriate to be spelled out in a MOU (memorandum of understanding),” he said.

Viker added that the refuge is not looking to amend the conservation plan, which is due for renewal in 2023. “Our intention is to continue to manage water levels as they are,” he said.

The refuge has been struggling to provide resources and funding for more studies and research at the lake, Viker said, and the co-management agreement provides the assurances the state needed in order to work with the refuge to get the help.

“That’s one of the keys to why this makes sense to us,” said Jeff Fleming, assistant regional director for external affairs at Fish and Wildlife’s Atlanta office.

In turn, the recreational goals of the state at Mattamuskeet will benefit. “This MOU is not signaling a new direction It’s not creating new projects” Viker said. “It’s enhancing coordination of resources to complete the projects.”

Pete Campbell, refuge manager at Mattamuskeet, said the two-year-old collaborative structure between agencies focused on research, monitoring, access and other issues. As a technical working group continued to look into the issues, he said, it became obvious that “we needed a tighter agreement.”

Why?

“Well I guess the answer is it is basically a way to leverage more resources for areas of common interest,” he said. “It brings more resources to the table. “

Rising Water

For the last two years, there has been unprecedented high water at Mattamuskeet, averaging about two feet above normal, Campbell said. In 2014, rainfall amounts totaled about 20 inches above normal; in 2015, there was 78 inches of rain, compared with an average of 49 inches. The pressure has forced the gates that allow water to be released to the sound to remain shut.

Steps have been taken in recent years to improve both the lake and recreational access. The lake has been stocked with fingerlings in an effort to rebuild populations of largemouth bass and black crappie. Those two fish, along with catfish and blue crab, are some of the most popular targets of fishermen at the lake.

Two continuously monitored water quality stations at the lake were installed in 2014 by biologists with the U.S. Geological Survey, Campbell said, and there is a commitment to operate them through 2019. There is also a system in place to measure salinity.

Campbell said that 55 percent of the lake’s submerged vegetation has been lost on the east side, and about 17 percent on the west side. Nutrients and sediments in the lake create turbidity that diminishes clarity and blocks light for the plants that are important food for the fish and birds.

The refuge also now has a staff biologist and water quality specialist who is working on a hydrological model of the lake.

“We’re looking at the entire watershed because this is sort of a preview to the effects of sea level rise on this landscape,” Campbell noted.

Fewer birds are coming to the lake – counts of ducks, geese and swans went from a normal of about 250,000 down to about 180,000 in late December. The biggest reason, Campbell said, is that the water is too deep for the birds to reach the vegetation.

The goal of the new plan is to develop a comprehensive approach to water management at the watershed scale, Campbell said. “And that’s going to take a lot of people and a lot of cooperation and a lot of collaboration,” he said. “It’s complicated science and politics.”

Mark Carawan said that one of the goals of Save Mattamuskeet Lake, a 900-member citizens group critical of refuge management tactics, was to have the Wildlife Commission take over management of water levels at the lake.

The new agreement, he noted, could allow the commission to better manage the lake, and in the process restore the vegetation and the bass fishing.

“I just believe the state is willing to come in here with more studies and more manpower,” he said.

Carawan’s family has owned a motel and tackle shop on the lake since the 1940s. Over the years, he said, the lake has lost much of its wildlife that attracted scores of visitors.

“It has gone from thousands of people fishing here March, April, May and June,” Carawan said, “to zero.”

Save Mattamuskeet Lake, he said, would like the lake to be kept at a constant level in the summer, and to be held higher only when levels drop so low that the fish would be hurt.

But now it’s the opposite problem. Nobody has ever seen so much rain and the levels get so high. Nothing is draining anywhere, and people’s yards and farm fields are flooded.

The solution, Carawan said, would be installing large pumps at all the water control structures canals.

“The farmers are saying SML has done this to us,” Carawan said. “It hasn’t – God has. We didn’t never ask to hold water in the lake at the level that would do this.”