Second of two parts.

KURE BEACH — One of the biggest challenges facing the threatened Carolina gopher frog is that their natural habitats, upland ponds surrounded by pine savannas, are becoming more and more scarce because of development and other factors.

Supporter Spotlight

That’s why the N.C. Aquarium at Fort Fisher and the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission are working together to help the species survive. Wildlife Resources began adding staff about 15 years ago to focus on non-game species.

“During the last six or eight years we have hired three folks to work on reptiles and amphibians specifically. We knew they were in trouble but we wanted to find out how much trouble,” said Jeff Hall, a biologist with the commission.

Researchers are set to head out into the woods this month to continue the head-start program for the gopher frogs. Work has already begun.

“Just as soon as we finish up raising frogs from the previous year we’re on to getting our tanks ready for the current year. We’re getting supplies ready now,” Hall said recently.

The frogs are a winter-breeding amphibian, but that’s not to say icy temperatures get them in the mood for love.

Supporter Spotlight

“If we get a day in the 50s they very well may start looking to breed,” Hall said. “In the next couple of weeks, things should start ramping up. Once we find eggs we start all over again. Then we’ll release the metamorphs in June, July or August, depending on how fast they grow.”

It’s not a high-profile project, but Nate Akers, a conservation and research technician at the aquarium and manager of the aquarium’s part of the gopher frog project, said hunters, birdwatchers and others who come across the teams when they’re in the woods are often curious about what’s going on, and that’s a good thing.

“Just being out here and being seen helps gopher frogs because people know they’re out here now,” Akers said.

Scattered Habitats

The frogs’ habitat is only in scattered locations across the region. Where ponds exist, the sites do not always get the prescribed burns or wildfires needed to maintain open areas. The lack of fire at some ponds has allowed full canopies to develop shady areas in which frogs do poorly. Sunlight is needed for the plants that shelter eggs and provide food for tadpoles.

Many sites lack an adequate amount of undeveloped land surrounding them. Gopher frogs spend only a short part of their lives in wetlands and then they move up into the woods, as much as a mile or two away from the ponds where they hatched and spent their early lives.

“Many of the problems are ones we can easily recognize, habitat loss, fragmentation due to development, lack of prescribed fire that allows these habitats to grow up. If there are things like that we can readily see, then there are things we can do to try and correct it,” Hall said. “Sometimes there are other factors and those things are harder to wrap our hands around.”

In the wild, ponds can dry up, meaning certain death for tadpoles. Things don’t get much easier as they emerge from the water, about 12 weeks later. Fire ants are a big predator for new metamorphs. People, too, can unknowingly create hazards for the frogs.

Akers said tire tracks in the woods, where vehicles have strayed from the unpaved roads, are an example of the threat human activity can be to the frogs’ survival.

A fresh rut from a four-wheel-drive truck fills with water during the first rain and entices frogs to lay their eggs, Akers said. The problem is that the water in these tiny, temporary ponds soon evaporates, leaving only a thin mat of black organic goo – tadpole remains.

A Safer Alternative

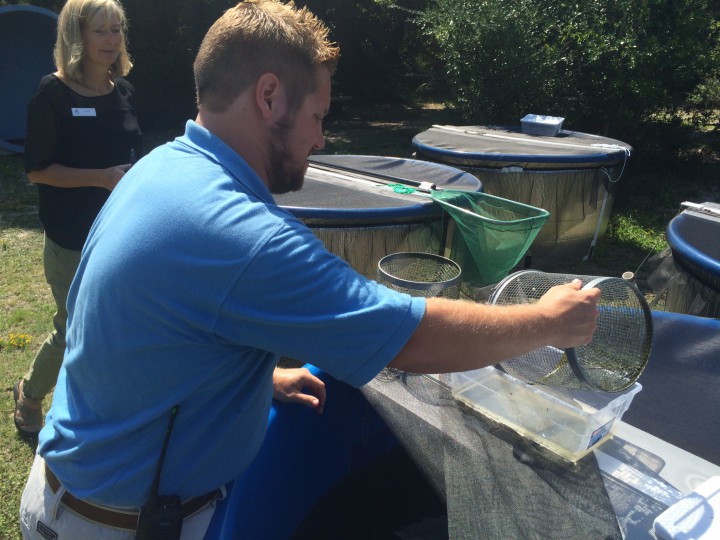

At the point in their development when young frogs in the wild would head for dry land, Akers and his team from the aquarium provide a safer substitute for the frogs’ natural habitat, raising them in tanks at the aquarium until they reach metamorph stage, when their tails disappear, legs emerge, gills stop functioning and lungs take over.

“Each tank is designed to be as close to a self-sustaining natural environment as possible,” said Akers, a Rocky Mount native who is set to graduate in May with a Bachelor of Science in marine biology from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington.

In captivity, the frogs emerge from the water as metamorphs and find safety inside mesh minnow traps placed at the surface of the water in their tanks. This helps prevent them from drowning until they can be collected by aquarium staff and moved inside until they can be released.

In 2011, when the aquarium and the Wildlife Resource launched the effort as a pilot program, conservationists released nearly 300 frogs. Only about 132 frogs were released between August and October, 2015. Akers said there were some snags that kept the numbers down last year.

“This year was a learning experience,” Akers said, “but there’s been more successes than setbacks.”

One setback this year came when a water softener was connected to the line that fed the water supply to the tadpole tanks. Metamorphs require a high level of calcium in their water for proper bone development. Although the water supply at the aquarium initially tested OK for calcium, that changed after the water softener was installed.

Also, the protocols from the 2011 study included a typographical error regarding the food dosage for tadpoles, resulting in less food than should have been provided. As a result, some metamorphs started to die. Akers said the complications reduced the success rate for this first full year of the project, but some problems were to be expected.

“We found that we are very good at identifying and correcting problems,” Akers said. “There were no major errors, just a few things we couldn’t do a lot about.”

Those unanticipated problems led to a new set of protocols that should help to head off potential complications this year and in future years, Akers said.

“We helped. Did we help as much as we wanted? Maybe not but we released enough frogs that it’s going to make a difference,” Akers said. “It was a resounding success and if there are problems in future years, we know we’ll be able to tackle it.”

It’s Working

In 2011, the goal of the pilot program was to successfully raise and release gopher frogs in a single pond. Two years later, a frog from that first-year release was found while calling for a mate.

“So we know it worked,” said Aquarium Director Peggy Sloan.

How do they know for sure? The frogs, while at the aquarium, were each marked with a visible implant elastomer, or VIE, a medical-grade, two-part silicone-based material that’s injected as a liquid into the frogs’ transparent or translucent leg tissue. The material cures within about 45 minutes to form a pliable, solid and brightly colored dot that researchers say poses no harm to the animal but remains externally visible.

Different colored markers are used to identify when the frogs are released. The elastomer is available in various colors, including fluorescent colors, that can be clearly seen in ambient light and are particularly visible with special ultraviolet flashlights.

The tags are injected just before release time back to the wild. Aquarium volunteers Allen Jones and Ellen Hindman assisted Akers in tagging the frogs last summer.

During the tagging process, the frogs are weighed and measured. Ideal weight for reintroduction is about three grams, or about the weight of a penny, but there are variations in the populations with Sunny Point frogs typically averaging a little larger than others.

The process can be challenging because the frogs tend to be lively and eager to hop around at this stage. Despite their energy, the frogs are fragile and delicate handling is required during the weighing, measuring and injecting of the markers.

When the frogs are returned to their natural habitat, the release team makes note of conditions in the field, such as assessments of water levels and alkalinity or acidity of the ponds.

The first frog this year emerged from the water on July 16, and at least one live metamorph was successfully retrieved from the tadpole tanks each day until fall.

Akers said the survival rate of the frogs in captivity, despite the program’s glitches in 2015, was still better than Wildlife Resources’ estimates for those left at nature’s mercy. In addition to the 132 frogs, 334 late-stage tadpoles were released in 2015.

This year, the goal is to release 600-800 frogs.

“We know we can do this and do a good job,” Akers said. “I think we’re going to do really great stuff next summer.”