The federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is preparing to offer leases for wind power off North Carolina at the same time that oil prices are at rock bottom. Expensive offshore wind energy seem like a fool’s pursuit, that is until the future is taken into account.

Land-based wind generation has gotten so cheap, it is nearly competitive with traditional power sources. The nascent U.S. offshore wind industry, however, is navigating in unchartered waters right now, both literally and figuratively.

Supporter Spotlight

By summer, a proposed sale notice will be published by BOEM, detailing the area or areas that will be auctioned off Kitty Hawk or Wilmington, according to Tracey Moriarty, an agency spokeswoman. Until then, she said, the location of available wind blocks is not known.

Despite steep upfront costs for offshore wind development, trends in renewable energy make it a good bet that costs will decrease as the industry matures.

“I think the whole continental shelf has good conditions to work in and build in,” said Paul Gallagher, the chief operating officer of Fishermen’s Energy, a company in New Jersey interested in offshore North Carolina wind. “Every state has adequate wind resources to sustain development to make it successful. The question is whether the market will sustain those projects.”

Gallagher said cheap natural gas makes it very difficult for offshore wind to be competitive. President Obama’s recent proposal to put a $10 tax on each barrel of oil, he added, could help even the playing field if Congress agrees.

But as Gallagher and other wind proponents have argued, the true cost of carbon emissions to society is rarely accounted for; nor are the long-term benefits of clean, renewable power.

Supporter Spotlight

With the federal government seeking to decrease carbon pollution, he said, incentives for offshore wind production are appropriate. The federal government late last year renewed a 2.3-cent-per-kilowatt-hour production tax credit for wind power that will gradually decrease until it ends in 2020.

“It’s a first project, so you’re doing everything with everybody who hasn’t done it before – so there is a premium to be paid,” he said of the Atlantic projects.

“It does need some supports. It needs some subsidies.”

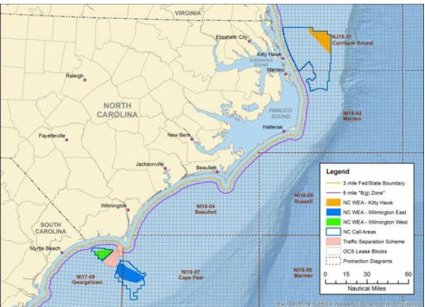

North Carolina is the latest East Coast state considered by BOEM for offshore wind farm development. The agency last year established three prospective lease areas totaling about 307,590 acres, one off Kitty Hawk and two off Wilmington. A revised environmental assessment released in September found no significant environmental or socioeconomic effects from issuing leases.

Five developers have been qualified by BOEM to bid on all or portions of the areas: Apex Clean Energy, EDF Renewable Energy, Green Sailene, Dominion Power North Carolina and Fishermen’s Energy.

More companies would be able to come in between publications of the proposed sale notice, which is followed by a 60-day comment period, and final lease notices, said Brian Krevor, environmental protection specialist in BOEM’s Office of Renewable Energy Programs.

Much of the concern expressed in public comments about North Carolina offshore wind proposals, he said, concerned impacts on the view from the beach of turbines, which can be 600 feet tall. Navigation issues and effects on wildlife were mostly addressed earlier in the process. The recent revision excluded areas where endangered right whales migrated off Wilmington.

“It is a very long and deliberative process,” Krevor said, “and we’ve spent a lot of time on those areas to try to eliminate these conflicts.”

Sales can be held just days after the final notice is published, he said, and leases can be issued to areas as small as 1/16th of a block, which are three-mile squares. Bidders can lease contiguous blocks, partial blocks or entire blocks. After leases are issued, a developer must submit for approval a construction and operations plan. The agency would then prepare an environmental analysis for the proposed project. The lessee has up to 25 years to develop a plan.

So far, four companies are interested in all of Wilmington East and Wilmington West areas. Four are interested in all of Kitty Hawk, and one company is interested in a smaller subset of blocks.

Numerous other Atlantic coast offshore wind projects are in various stages of the permitting process, including Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Maryland, Delaware and Virginia. According to the agency, BOEM has awarded nine commercial wind leases, generating more than $14.5 million in high bids for more than 700,000 acres in federal waters.

Block Island, in Rhode Island, recently started construction and is on track to become the first U.S. offshore wind farm. South Carolina is the most recent addition and is at the very early point in the public engagement process.

Often, BOEM is in the dark as much as anyone as to the likely outcome of bidding. “We normally, truly, don’t have a clear picture sometimes until a proposed sale notice closes,” said Will Waskes, project coordinator with BOEM.

But he declined to characterize the overall sentiment towards proposed projects off North Carolina. “We don’t really speculate on that for any of these projects,” Waskes said. “We’re regulatory agencies. We try to develop it in a responsible way.”

Gallagher, with Fishermen’s Energy, said that things heat up with developers about four months before a lease auction. Speculative planning is not the nature of the industry, he said. “It makes sense before an auction to really sharpen your pencils,” he said.

Charlie Smith, executive director of the Utility Variable-Generation Integration Group, a multi-national energy group focused on economic and reliable solar and wind generation, said that a recent analysis by investment firm Lazard found the cost of renewable energy has plummeted, in particular land-based wind power and solar energy.

“That is what’s driving the tremendous interest in wind and solar across the country,” he said. “This is unprecedented. It’s a revolution taking place technologically … I’ve been in the energy business for 45 years, and there’s never been a more exciting time to be in the business because of renewable energy.”

With more complicated regulations and technology requirements, offshore wind development costs about three times more than land-based wind, Smith said. “The cost will go down as the experience goes up,” he said.

Land-based wind generation, meanwhile, has been improved dramatically, Smith said, by building taller towers with longer rotors that more efficiently capture more wind.

“Not only is wind the lowest cost source of clean energy in the country today,” Smith said in a recent presentation in Southern Shores, “wind power is the lowest cost source of energy in the country today, period.”

And Smith is referring to mostly unsubsidized wind power costs.

“A lot of modern wind turbines have the potential to create a lot of energy at a lower coast than even coal,” said Jason Hoyle, a research analyst at Appalachian State Energy Center at Appalachian State University in Boone.

Amazon Wind Farm, on 22,000 acres straddling Perquimans and Pasquotank counties, is on-course to be completed by year’s end, said Paul Copleman, spokesman for developer Iberdrola Renewables.

A lawsuit filed in October against the state Department of Environmental Quality’s review of the project is not expected to affect the project’s plan, he said.

Once it is completed, the $400 million Amazon project would be the state’s first commercial-scale wind farm, with 104 turbines generating up to 208 megawatts of electricity.

But even with its higher costs, wind-energy production off the Southeast U.S. coast is a good value beyond its environmental benefits, said Chris Carnevale, coastal climate and energy manager for nonprofit Southern Alliance for Clean Energy.

When electric utilities are running at peak demand at the height of the hot summer months, they tap into more expensive and inefficient sources like combustion natural gas turbines to supply the extra power.

Those hot summer days coincide with the hours that wind turbines, helped by a natural dynamic known as the “sea-breeze effect,” run most efficiently, he said. The phenomenon results from cool air rushing inland as warmer air rises.

“So offshore wind peaks when utilities are firing up their most,” Carnevale said. “It can be way, way cheaper than the utilities firing up (natural gas) peaker plants.”

In fact, the power produced by offshore wind could allow utilities to avoid the need entirely to build such plants, Hoyle added, bringing down capital overhead and production expenses for the power companies.

“The actual cost to generate power at different hours, he said, “that’s not visible to the retail customers. That’s visible to only the utility companies.”

North Carolina has comparably low electricity costs, Hoyle said, but those costs are rooted in a vertically integrated monopoly system that is not as transparent or competitive as wholesale markets used in other states like California.

“There are trade-offs,” he said.

Carnevale said that it is the right time for the state to embrace wind power, including development in the Atlantic.

“Ultimately, we need to transition our energy,” he said “I would be really proud to have offshore wind towers off our coast.”