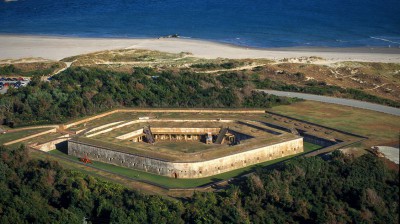

ATLANTIC BEACH — The date was April 23, 1862, and Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s Union army watched as a white flag was finally raised above the old fort. What had first seemed like a battle won in less than 24 hours had turned into a month-long ordeal trying to get Confederate troops to vacate the premises.

Fort Macon had been a strategic target because it guarded Beaufort Inlet and North Carolina’s only deep-water port. When the 400 men defending the place finally surrendered that day, the Civil War, for all intents and purposes, was over in this part of the Confederacy. The Yankees occupied the fort for the rest of the war, and the harbor it guarded became an important coaling and provisioning port for the blockading Union navy.

Supporter Spotlight

Almost 60 years after the war’s end, the restored fort and the beaches and marshes that surround it became a key addition to the state’s nascent park system. Millions of people have since walked the parapets, swam the beaches, fished the inlet of Fort Macon State Park. It is now among the busiest of our parks and last year was named the best of them.

Built for War

A place that so many now find beautiful and peaceful started life as an instrument of war. Construction began on the fort in 1826, in response to the realization that America’s coastline was largely helpless during the War of 1812. The Army Corps of Engineers built the fort over the course of eight years and according to Brig. Gen. Simon Bernard’s design. It was named after North Carolina’s eminent statesman at the time, Nathaniel Macon, according to nonprofit Friends of Fort Macon.

For the first 150 years of its existence, it seems like Beaufort, the town just inside of the inlet that Fort Macon protects, was always in need of protection from something. First, there was the Tuscarora Indians who for some reason didn’t like trespassers brutalizing them and forcing them off their own land. One Blackbeard the pirate in 1718 literally abandoned 300 of his men here who descended upon the town to do as they please. Then on Aug. 26, 1747, Spanish privateers sailed into the harbor, offloaded and invaded the town like Henry Morgan sacking Panama. The British did the same thing in 1782. Of course, the war of 1812 wasn’t much better as the Brits came sailing in repeatedly, demanding supplies for which Beaufort’s only defense was the homegrown privateer Otway Burns and his ship the Snapdragon.

Even Mother Nature had its eye on Beaufort when she spun the hurricane of 1825 that actually swept into the inlet a pathetic excuse for a fort that was Fort Macon’s halfheartedly built predecessor.

From Beaufort’s inception, every generation that lived anywhere near the town was forced to endure war, invasion, threat and privation. Fort Macon was built to change all of this.

Supporter Spotlight

The old five-sided brick and stone fort, with outer walls measuring some 4.5 feet thick, has had a long and interesting history standing guard over Beaufort Inlet and the surrounding coastline. However, after the Civil War, things kind of quieted down, and its roll of protectorate of this region began to change. There was a brief hiccup we call World War II of course, when the feds leased the old fort from North Carolina for a few years, but by and large, the real treasure that Fort Macon would come to protect is the natural world – in both direct and indirect ways.

There is a certain kind irony to be found, undeniably poetic, in a military fort coming to protect fiddler crabs and piping plovers. But for the grand old fort at the east end of Bogue Banks, that is exactly the role that this defensive structure has played the majority of its life. Though warfare may have been its intended use, the sands of time had other plans for Fort Macon.

The Complaining Dr. Coues

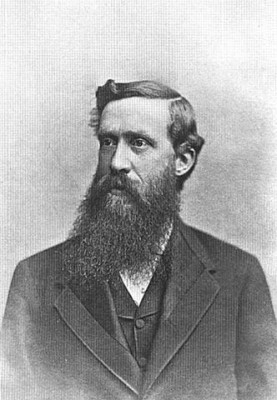

Elliott Coues complained a lot. He complained about the fort. He complained about his sleeping quarters. He complained about the hospital, the salt, the humidity, the malaria and the mold. He especially complained about the mold. Moldy books. Moldy papers. Moldy everything.

But Coues was also an ambitious man. He was as a doctor for sure. But he was also trained as a naturalist by none other than Spencer Baird, the founder of the Smithsonian Institution. His calling in life was never to be just an army surgeon. Coues had dreams. He had goals. But he was no Humboldt or Darwin, with the inheritance and financial means to explore the world. And so like many an early 19th century member of the intelligencia without the means to see the world, he joined on with the army as a surgeon hoping they would foot some of the bill – which is how he ended up stationed on Bogue Banks.

Arriving at Fort Macon in February of 1869, Coues set about trying to see past the squalid conditions that he was expected to work in and headed straight into the boot-sucking salt marsh to have a look around his new home. What he was to find was an island quite unlike the one we know today. In all, there were only a handful of people living on Bogue Banks other than the soldiers at Fort Macon, and most of those were seasonal whalers. Maritime forest, with gnarled old live oaks dripping with the vines of wild grapes, covered much of the banks that would lead to the modern name of Emerald Isle.

Bogue Banks was in an almost pristine state. There were no marinas, no hotels, no bridges, no roads, no developers. All of that would come later. What there was, was a seemingly endless stream of migratory birds in the springtime. Oysters so plentiful that a bushel sold for just 30 cents in Beaufort. Nets full of mullet. And from foreshore to salt marsh, the whole place was a 19th century naturalists’ dream come true.

Coues was a Smithsonian protégé, a trained naturalist skilled in the arts of skin collecting. He was educated in the methods of detailing observations of the natural world. And so Coues, the whiney army surgeon began to write – prolifically. He wrote about birds. He wrote about reptiles. He wrote about bugs. And over the following two years, he completed the most extensive biological survey of any place in the American South. The whole lot would be compiled and published in a five-part series in the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia titled “Notes on the Natural History of Fort Macon.”

Coues was not the first naturalist to write about the area. That honor would go to another Smithsonian naturalist, William Stimpson, who had already published his “Trip to Beaufort N.C.” in The American Journal of Sciences and Arts. However, Coues’ writings were quickly putting this place on the map for serious naturalists, and he actively sent out invitations other likeminded scientists to visit his Fort Macon and Bogue Banks. The result was a steady influx of bird nerds and fish experts to the little town of Beaufort. And within 10 years, John Hopkins University was running what may be the first marine science laboratory in U.S. history out of the Gibbs House on Front Street in Beaufort.

Evolution of a Science Center

After John Hopkins opened up shop, the University of North Carolina followed, renting Duncan House just down the road. UNC, Hopkins, along with the state universities of Virginia, Georgia and South Carolina, all pitched in money to buy land on Pivers Island, between Beaufort and Fort Macon, to donate to the U.S. Fisheries Commission for construction of their new laboratory. Three decades later, Duke University would also join by establishing its own marine laboratory. Today, three university marine laboratories and a federal fisheries lab combine to make the Crystal Coast one of the largest hubs of marine science in the country. Not a bad legacy to leave behind for an eclectic army surgeon hunkered over pen and paper by candlelight while stationed in that moldy, old fort.

As for Fort Macon, that pentagon-shaped sentinel that has watched over Beaufort Inlet since it was first constructed in 1826, the whole place was turned into North Carolina’s second state park, after Mount Mitchell, in 1926. But the creation of the park would encompass more than just the physical structure of the fort. The boundaries of Fort Macon State Park would reach out to encompass 424 acres in all, ultimately protecting some of the most important and productive habitat on the island. Though this is today the smallest of all our state parks in North Carolina, it is twice the size of the Roosevelt State Natural area on Bogue Banks, making Fort Macon the largest permanently protected swath of land on the island.

Thus has been the legacy of this old fort. Once defensive sentinel standing guard over this stretch of otherwise unprotected coastline, Fort Macon sparked the marine science industry of the Crystal Coast, inspiring countless biologists who now ply waters the world over.

As a state park, the fort now plays home to nesting sea turtles, migrating shorebirds, storm-battered pelagic seabirds and a long strand of undeveloped white sandy beach, unmolested by the blight of development. These walls have protected a way of life, a rich and diverse ecosystem, and the psychological wellbeing of those who recreate (re-create) on its beaches. With such a history, with such a legacy, it is for these reasons that Fort Macon was named North Carolina’s No. 1 state park recently, as this red brick fortress continues to stand guard some 190 years after it was first built.