“Easy beast,” I said to chef Kyle Lee McKnight shortly after I met him in 2010. The local foods movement that had been gaining momentum nationally since 2000 was just catching on in Wilmington. McKnight was blasting restaurants that claimed to serve local foods but really weren’t.

McKnight had caught my eye some months earlier on Facebook. I noticed him chastising another chef for using strawberries out of season in North Carolina. McKnight wasn’t exactly gentle.

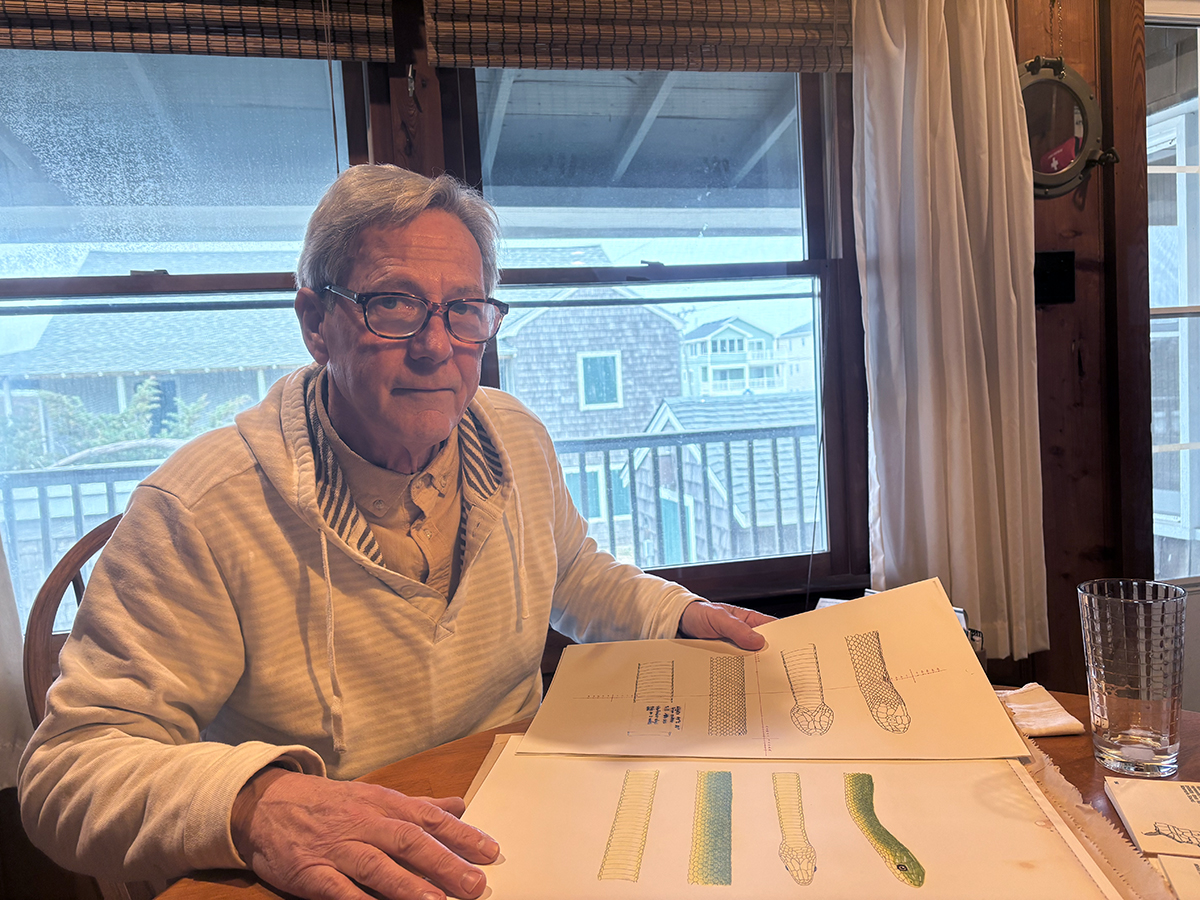

Supporter Spotlight

I interviewed McKnight not long after that at the hugely popular downtown Wilmington restaurant where he worked. The place was packed more than a few nights a week. Summer tourist season was especially crazy. Still, much of the produce that the kitchen used was grown locally. A lot of it McKnight raised on an acre and a half he was farming organically near Carolina Beach. That was the point of my interview with him. McKnight worked the land, harvested the crops and canned, froze and pickled the harvest to help keep the restaurant stocked in winter.

I learned how McKnight commissioned organic farmers to grow what he himself could not produce in large enough quantities. He also sourced happy, free-range hogs for the charcuterie he cured in a secret space tucked between walls near the ladies room. If you fixed your lipstick at a particular sink, you caught the undeniable scent of an Italian salumeria.

McKnight started all this a few years before other Wilmington-area chefs even noticed the local foods movement. I left that interview thinking, “That guy is a beast.”

“I’m really a nice guy,” McKnight has told me again and again over the years. And he really is. That chef McKnight Facebook spanked for serving out-of-season strawberries? He ended up McKnight’s friend, and McKnight shared his farmer and fisher contacts with the guy.

Blunt but polite, serious but passionate, McKnight has what seems like an unparalleled drive among N.C. chefs to not only source local food but help farmers and fishers expand markets for their harvests. Additionally, McKnight has deep respect and appreciation for N.C. food culture, even though he’s not a native Tar Heel.

Supporter Spotlight

Born in Germany and raised in Washington, D.C., McKnight has cooked in France, Miami, Argentina, Charleston, S.C., and the Virgin Islands. He grew up vacationing with his family on the N.C. shore. When his mother moved to Carolina Beach, McKnight followed in 2005. Something about the place stuck.

Tour a McKnight menu and you’re bound to find a taste of the N.C. coast down to the S.C. Lowcountry, even now that McKnight helms stoves far from the beach at Hickory’s Highland Avenue restaurant. The dining room seats 145, the event space can host nearly 700 people, but farmers and artisan food makers still carry their bounty directly to McKnight through the restaurant’s back door.

“North Carolina shrimp and grits” has been on the menu since the beginning. Starters include Carolina chowder with bacon, sweet potato, cornbread, black eyes and smoked oyster cream. Crispy fried N.C. oysters arrive with pickled ramp cornbread rouille.

Many chefs and restauranteurs will tell you that acquiring local foods is too spotty and expensive. McKnight not only finds ways to make local food work on his menu, his efforts and cooking have earned Highland Avenue a place among Southern Living magazine’s 2015 list of the South’s best restaurants and McKnight’s charcuterie a Good Food Award. Garden & Gun in 2015 named McKnight among five Southern chefs to follow on Instagram, noting “Plenty of chefs appreciate local produce, but few take it as far as this hardworking chef.”

McKnight still works the line just about every night at Highland Avenue. He clocks well above 40 hours a week between prepping, cooking, making charcuterie and working with the people producing the bounty he uses. Still, he took a little time to talk to Coastal Review about his work.

How does the North Carolina coast influence your cooking?

How does it not? The influence came from being at seafood markets … hanging out around the docks over there by Blackburn (Brothers) Seafood (in Carolina Beach), seeing all the different stuff that came in and (working for Carolina Beach restauranteur) Ralph Freeman. I was 19. We’d have beautiful tuna. We’d have trigger before it got real popular. We’d have tilefish. We’d have sheepshead. But he was always eating, like, sugar toads, or toad fish. Or spots and croakers. You know, what old-timers ate … so I learned a lot about the bycatches. You know, I will always be the proponent for N.C. seafood because I think it’s so much better than anywhere else on the East Coast. There’s just something about the water. The seafood is so much better … I know it’s not in my head. I can taste the difference between two species of fish from two different locales.

Getting that North Carolina seafood to the mountains can’t be easy?

I use a lot of the bycatches, and that’s what I’m really going for. You know grouper is a huge fishing industry in North Carolina, but I think it’s overfished. So, I’m always looking for sheepshead, for monkfish, some of the tilefish. I’ve gotten sugar toads a few times. It’s just tricky getting stuff sent from the coast sometimes. I’m using a distribution company that I have long-time ties with. Some distributors will say, ‘Oh, we’ve got N.C. scallops,’ and I’m like, ‘Well, how come nobody else has N.C. bay scallops, and you’re telling me they’re N.C. bay scallops?’ I’ve been around the coast long enough, and I know the times of year when these seafoods and these fish run. I don’t always have N.C. fish, but I always have N.C. shrimp. And I will be the first one to say that I serve frozen shrimp. They’re not going to come to your plate frozen, but I make sure my shrimp is always from North Carolina. I appropriate deals when they’re in season. I’ll say, ‘Put up six, seven hundred pounds for me,’ and make commitments to people that I’m going to buy this. And 90 percent of the time, I’ll have N.C. crab. And I pay more expensive prices for it, but I do it because that’s what I feel compelled to do for the economy of the coast, just like I buy agricultural products in the area where I am now. It directly affects somebody. It helps their children. It helps pay bills.

It’s not just the coast’s seafood that has influenced your cooking.

No, not at all. You know agriculture, but it’s also the cooking style, honoring some of the traditions that are cooked up and down the Southeast, from the Lowcountry, when I cooked in Charleston, to Wilmington. They’re very similar, the style of cooking, the ingredients they use. It really lends well to who I am as a person, and it enhances my food greatly.

When did you become “the beast?” When did you get into going out of your way to source local food?

I was introduced to it young, when I was (cooking) in Charleston. You know it was the ethical thing to do. It was the way you bought food. And I had many jobs where I couldn’t do that. I didn’t have the ways and means to contact people I wanted to contact. But for me, everything was relationship based. I wanted to know the people that were actually producing or raising or harvesting these food because the love and the care that goes into it, I believe, translates into the taste. The food just tastes better … and it’s about helping and it’s about sharing. I wanted people to know where their food came from, and that there are people and there are faces and everybody deserves a voice.

In North Carolina, it’s illegal for restaurants to buy directly from fishers. How do you cultivate relationship with fishers that then translates into you getting local seafood?

It’s all trust-based. Once you develop a relationship and trust with them (fishers), you can introduce them to the right people, (a wholesaler) who genuinely cares, and these fishermen bringing in X amount of, say, these five different species to the right people that are consistently going to buy and who are going to be honest in telling you (a chef) where it comes from, and then they (wholesalers) can help distribute the product from there.

And you work with farmers in a similar way?

Yep. I’ve gotten meat raised specifically for me by a farmer through a company I’ve consistently bought from, Eastern Carolina Organics, and the pig has been graded out. It’s been N.C. Ag-certified, USDA-certified. If I wasn’t able to take as much as I thought I could take, then I call other chefs to see what they can use, but I try not to over commit ever.

In the first few months you were at Highland Avenue, you started introducing the area to your favorite coastal purveyors, namely Rose Hill organic farmer Herbie Cottle of Cottle Organics.

He’s a guy I beat down about growing lettuce (for me when I worked in Wilmington), and now he’s doing great with it because of his connection with Eastern Carolina Organics. If I was in Colorado, I would probably try to get the man’s produce because it’s that good, and we have that strong of a relationship. And the same with seafood. People ask me, ‘How come you don’t have salmon? How come you don’t have tilapia.’ You know why? Because it does nothing for our state; it does nothing for our fishermen. I buy food from friends, period.

A Few N.C. Local Food Purveyors |

Charcuterie is a serious part of your craft, and your meats have a decidedly N.C. touch. I’m thinking of your recent salami flecked with diced sweet potatoes.

I call it progressive preservation. I want to help my friends out as much as I can. I want to honor the animal as best I can. So if I can make something that has inadvertently been touched by every one of my friends, then I can serve it to guests, who I consider new friends, for me that’s the ultimate way of saying ‘thank you.’ I think that salami is going to end up a signature of mine. Sean Lilly Wilson who owns Fullsteam Brewery in Durham is a really good friend of mine, and he makes a Carver sweet potato lager. So I use that beer. And then, friends of mine up here (in Hickory) who grow the white sweet potato O’Henry, which is my favorite sweet potato, and then I use Beauregard sweet potatoes that were grown by my friend Jamie Swofford in Shelby, and I also use a little bit of Covington sweet potato that was grown by Herbie Cottle. My whole thought was to produce what I would call a ‘North Carolina salami.’”

You’re in the mountains now, but you visit family on the coast regularly. When you return to the shore, what’s the first thing you want to eat?

Well, um, I try to get Britt’s donuts (laughs) and fried shrimp on Ocean Grill’s pier or oysters.

Learn More

- Bigger Restaurants Can Feature Local Food

- Highland Avenue Restaurant

- The South’s Best Restaurants

- Good Food Awards

- Chefs to Follow on Instagram

- Britt’s Donuts

- Ocean Grill