Second in a series

WILMINGTON — The increasing demand on drinking water resources is one of the major issues facing those who live and work in Eastern North Carolina, according to a U.S. government report.

Supporter Spotlight

State officials estimate the New Hanover County population, now more 216,000, will increase by more than 38 percent by 2030 and by 100,000 people in the next 25 years. That’s not including the seasonal tourist population, which swells during the warmer months. Add in industrial development and the potential for problems grows. Then, there are the other growing communities in the larger Cape Fear region – many of which depend on the same groundwater or surface-water resources.

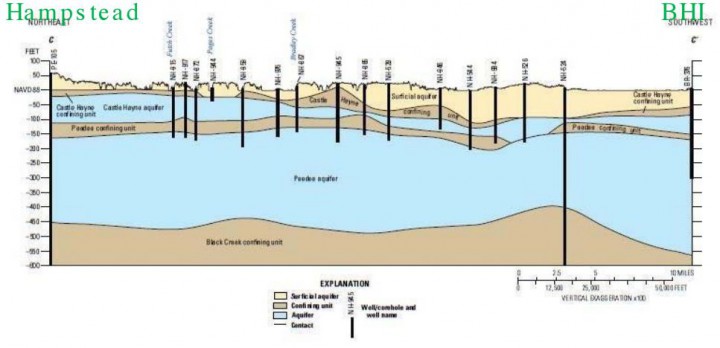

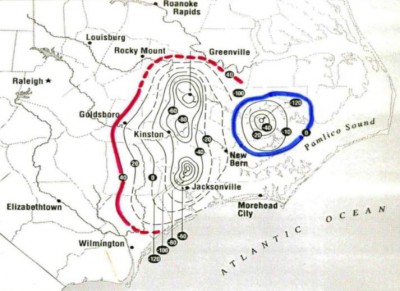

Groundwater and surface water resources are related but problems below ground aren’t as easy to spot and until recently little research has been done. A 2012 report by the U.S. Geological Survey showed that because of long-term over pumping, groundwater levels in the Peedee, Black Creek, and Upper Cape Fear aquifers of the state’s central coastal plain in counties to the north of New Hanover County have declined substantially over the past 30 years. The survey, which was done in cooperation with Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, was the first scientific study of its kind in more than 40 years.

“It was a good partnership, they have expertise and know-how,” said Mike Richardson, the authority’s water resource manager. “Naturally we want to see what the current and the future is. We can’t prepare unless we know the things that are going to affect us. This was an opportunity to learn more about the current groundwater situation and the impacts of saltwater as it continues to encroach into these aquifers.”

Kristen McSwain is a USGS hydrologist who worked on the study. She said the report provides merely snapshot comparisons of data from 1964 and 2012 but big changes have occurred over the years.

“There’s been explosive growth in the area and groundwater is a resource that’s heavily used,” McSwain said. “It (the study) was basically to look at groundwater quantity and quality in comparison from the ‘60s to today but with only two data sets it’s hard to draw conclusions. This is not a long-term statistical study.”

Supporter Spotlight

McSwain said the specific reasons for the declines in groundwater quantity can’t be readily identified, based on the results of her work. “All I can say is they declined. I can’t say why and I can’t say when. What it indicates is a need for increased monitoring,” she said.

Groundwater chemistry showed similar changes in the comparison, including indications of saltwater intrusion into the freshwater aquifers. “But again, it shows that monitoring is needed. I don’t know when it happened,” McSwain said.

A National Water Census

Research is continuing at the state and federal levels. The scope for these studies goes far beyond just groundwater and also beyond New Hanover County’s borders.

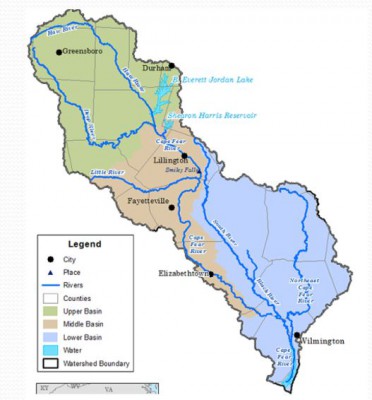

New Hanover County’s drinking water supply comes from a combination of surface water and groundwater. Wilmington relies mainly on the Cape Fear River as its drinking-water supply, and so do many other communities.

The Cape Fear River basin, the state’s largest river basin, extends from near Greensboro and High Point in the Piedmont to the Wilmington area on the coast. The area includes all or part of 27 counties. More than 21 percent of the state’s population lives in the more than 9,000-square-mile basin area.

A state law passed in 2015 authorized the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality to study all uses of ground and surface water in the Cape Fear River Basin, including public water systems, industrial facilities and agricultural operations.

The study is supposed to identify potential conflicts among the various users and offer recommendations for developing and enhancing coordination in order to avoid or minimize those conflicts. An interim report is expected this year with the final report due in 2017.

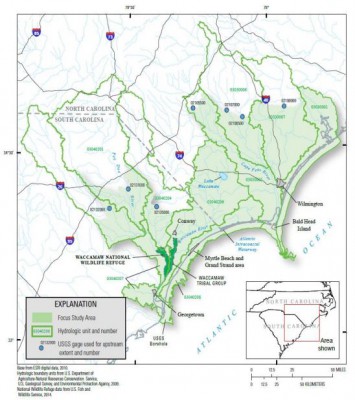

A separate but related study is underway at the federal level. The USGS Coastal Carolinas Water Availability Study is a step toward assembling a national water census. Chad Wagner, USGS associate director for investigations at the N.C. office of the South Atlantic Water Science Center in Raleigh, is heading up the work, which began in October

The study is different from the state’s work in that it’s a three-year project due for completion in late 2018 or early 2019, and it’s wider in scope, including coastal basins in southeastern North Carolina and northeastern South Carolina, but there is collaboration.

“We’ve definitely been in communication with the state and we let them know what we’re doing,” Wagner said.

The goal is to use the results to develop and refine water-use estimates for agriculture, public supply and industrial sectors. The water-use data will be site-specific to allow tracking of water from its source to the ultimate users and its disposal, both within and beyond the study area.

For surface water, models will be used to evaluate potential changes in water availability and salinity in response to various water uses and climate-change scenarios. Ecology, including fish and plant life, will also be examined in terms of responses to changes in flow.

Groundwater flow models of water-supply aquifers will be used to simulate the effects of various usage scenarios and gauge the problem of saltwater intrusion from pumping.

The coastal region was selected for study because of current and projected population increases and the effects on fresh and saltwater ecosystems. The recent history of frequent coastal storms and droughts here was also a factor. The area is also deemed a groundwater capacity-use area, or an area where demands on water resources have reached a point where coordination and regulation may be needed to avoid threatening or impairing those resources. The region is also considered vulnerable to sea-level rise, land-use changes and climate change, in terms of effects on aquifer water levels and saltwater intrusion.

Local Planning

New Hanover County is working toward completing a comprehensive planning document for future growth with goals for preserving and protecting water quality and supply. The plan recommends establishing a groundwater- and aquifer-protection ordinance.

“There’s an increased awareness of the protection of our drinking-water supply,” said Chris O’Keefe, New Hanover County’s planning director.

Dylan McDonnell , a long-range planner with New Hanover County’s planning department, said the county expects to have the planning document completed by early spring. The effort, which began more than a year ago, includes input from a 12-member advisory committee made up of local residents and approval by the county planning board and board of commissioners.

The advisory committee raised the issue of water resources, McDonnell said.

“There was not a concern as far as quantity,” he said of the county’s water supply. “We just want to make sure we have sustainable sources for the future and to make sure we’re not degrading them to the point where we can’t use those sources. We weren’t singling out certain industries or looking at industry in general, we were looking at creation of our land-use map, an overall, general vision that the county has for the future.”

The plan is also not a zoning ordinance, McDonnell said. “That’s the next component after we finish with the comprehensive plan, revising our zoning ordinance, which was written in 1969.”

Meanwhile, officials in charge of the county’s public water system are putting in place new technology also meant to ensure there’s enough water for future demand. This includes a new process of pumping treated water back down into the aquifer for storage until it’s needed. The process, known as aquifer storage and recovery, or ASR, is set to become operational this year at a plant near Wrightsville Beach in the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority’s system.

The system is expected to provide cost-effective, seasonal storage of treated water, said Mike Richardson, water resource manager with the authority. Part of the cost savings is having no physical tank to maintain. The ASR system may also allow the water treatment plant to operate more efficiently during lower-demand periods while being available to meet the need during periods of peak demand. The system can also provide an emergency supply and could slow or reverse the effects of saltwater intrusion in the aquifer.

Economics and Race

There are more than 6,000 regulated public water systems in the state, according to the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality. About 75 percent of the state’s population lives in areas served by community water systems, and many others and visitors to the state are served by other types of public water systems, such as workplaces, schools, parks or restaurants.

Homeowners in communities without access to public water rely on domestic wells. North Carolina has the fourth-highest number of private well users in the country. The high rate of dependence upon wells and septic systems is partly because of the rural nature of the state with its many unincorporated communities. Economics and race are also factors.

A study in 2015 by the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill found that 26 percent of North Carolinians rely on private wells, as compared with 14 percent nationally and 49 percent use septic systems, compared with 24 percent nationwide.

Septic system failures can lead to contamination of well water, and the high density of septic systems in rural communities is a public health risk associated with increased incidences of bacterial and viral diarrheal diseases, according to the report by Julia Marie Naman, a 2014 Gillings School alumna, and Jacqueline MacDonald Gibson, associate professor of environmental sciences and engineering at the school.

“Unequal access to water and sewer services can have considerable health effects,” they write, “and disproportionately burdens the politically vulnerable.”

Naman conducted interviews during 2013 with 25 elected officials, health officials, utility providers and community members in North Carolina’s New Hanover, Hoke and Transylvania counties. She found that economics was the primary factor determining whether access was granted to municipal services. Improved public health was described as a minor reason.

Problems with septic systems tend to be underreported, according to the study, because local health departments rely mainly on homeowners or their neighbors to report failed systems and repairs can be costly.

The Gillings research team has also found statistical evidence that race plays a factor in who does and does not have access to municipal water services in North Carolina. This lack of access also increases people’s health risks.

The research concluded that better understanding the health costs and benefits of water and sewer extension and considering these factors in the local decision-making process may help address disparities in access to municipal services.

Part I: Drinking Water: An Imperiled Resource

Part III: Groundwater: Gauging the Titan Effect

Learn More

- USGS and Cape Fear Public Utility Authority Report

- Groundwater Protection: Underground Injection Program

- Disparities in Water and Sewer Services in North Carolina