COLUMBIA — Just a few miles off U.S 64 in Tyrrell County, nature lovers can venture into the dense thickets of the Palmetto-Peartree Preserve, a haven for a community of protected woodpeckers with arduous housing needs and fascinating social habits.

It won’t be easy, however. The former timberland-turned-endangered species mitigation site and nature preserve has changed hands recently, and in the process nature is taking its course.

Supporter Spotlight

Established in 1999 by the nonprofit The Conservation Fund, with funding provided by the state Department of Transportation, the 10,000-acre preserve was created as a mitigation bank for the red-cockaded woodpecker, an endangered species. Protection of the bird at the preserve is intended to offset its habitat loss at DOT construction sites throughout the state.

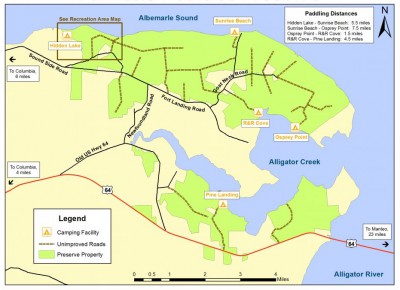

The preserve, situated along the banks of the Albemarle Sound and Alligator River, has turned out to be a surprisingly good habitat for the woodpeckers. Despite their historic preference for a fire-maintained open pine forest, the birds are thriving in the heavily vegetated mix of hardwood and pine forest.

It’s not unusual for the woodpeckers, listed as endangered in 1970, to spend about nine years excavating a cavity in a 100-year-old or older live loblolly pine tree, and as long as 13 years in an old longleaf pine.

Reluctant Owner

In July, The Conservation Fund transferred ownership of the preserve to DOT, which is looking for another agency or nonprofit group to take it over.

“That was kind of the plan for a very long time,” said Justin Boner, The Conservation Fund’s director of real estate in North Carolina. “The Conservation Fund has always considered itself a temporary owner.”

Supporter Spotlight

The preserve is named after two land forms along the shoreline known as Palmetto Point and Peartree Point.

Boner said the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which manages several refuges in the region, lacks the staff or resources to also manage P3, the preserve’s shortened name. But the agency, which oversees management of endangered species, maintains a partnership with the preserve.

“The initial deadline was five years,” he said. “I think it just became clear that we didn’t have an easy agency identified. So DOT stepped up and took charge.”

But the state transportation department is a reluctant owner.

“DOT is not interested in the business of managing these large areas of property,” said Phil Harris, manager of the department’s Project Development and Environmental Analysis Branch. “We don’t intend to hold it for a long time.”

Despite its lovely alliterative and Southern-sweet name, the preserve is a rugged, remote and somewhat neglected example of unfettered wilderness. Prolific undergrowth in the habitat, a mix of bottomland swamp, hardwood and pine forest, has nearly concealed walking paths to public viewing areas and boardwalks.

Logging roads are rutted and vehicles often must straddle a thick mound of tall grasses growing between tire tracks. Even the signage is faded and outdated. And not to mention the unrelenting assault from various biting and buzzing bugs, energized at the scent of a rare human.

Harris said there had been some recent road maintenance in the preserve to improve access for their consultants, but “we kind of want it to stay in its natural state.”

For those who prepare properly for a trek into the Triple P – its alternate nickname – they will be treated to the unusual sight of the red-cockaded woodpecker. That is, if they are there at dawn or dusk, when the birds leave and return to their cavity.

“The one unique thing about that species,” Boner said, “is there’s a lot birders who want to see those birds. They are incredibly reliable. As long as you are there at those times, you are pretty much guaranteed to see them.”

In 2002, there were 25 active clusters in P3, and the long-term population goal was 33. Today there are about 32 clusters, the term used to describe the aggregation of cavity trees used by a family group.

As interim owners, the DOT will continue to maintain the habitat, which is designated as an Important Bird Area by Audubon North Carolina. A 2002 management plan is in the process of being updated.

More Than Woodpeckers

Although the preserve was created to protect the red-cockaded woodpecker, it also provides habitat to the bald eagle, peregrine falcon, and more than 100 migratory bird species, in addition to the red wolf, American alligator, bobcat and black bear.

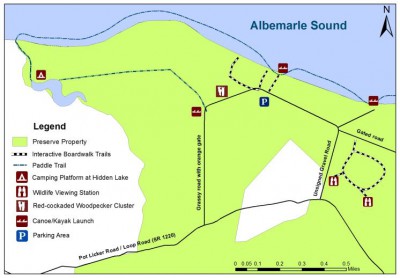

The now-overgrown boardwalk trails and numerous dirt logging roads provide public access to the preserve, and there is interpretive signage on the designated Shoreline Trail that goes to the Albemarle Sound. The ¾-mile Woodland Trail has two wildlife viewing stations, and there is a paddling trail for kayakers.

For campers looking for something a little different, there is a camping platform in the middle of Hidden Lake available to rent.

But by far, it is dedicated birders who make the most use of the preserve.

John Hammond, endangered species biologist in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Raleigh field office, said that for the last 15 years, he has taken between six and 15 birders at a time out to the site as part of the annual, fall Wings Over Water event.

“You get to see the birds right when they wake up,” he said. “Probably at 6:30, we’re out there. It’s really fun to see.”

One bird will open its eyes and chirp – their call sounds like “sklit.” Then another chirps, and soon they’re all chirping. Birders equipped with binoculars can readily find the cavities by looking about 6 feet up live pines for the painted white bands that mark cavity trees.

“I think most people are pretty excited,” Hammond said. “They’ll be some high-fives and oohhs and awws, and ‘isn’t that cute?’ ”

Social Birds

Red-cockaded woodpeckers – or RCWs, as U.S. Fish and Wildlife refers to them – are very social and live in family groups that typically consist of a mated pair and about three to six male “helpers” – usually mature offspring. Each group exists in clusters of cavity trees and a large defined home range. Once females mature, they will usually leave the group to seek a mate, but most males stay behind.

“The male is very tenacious,” said Hammond. “He’ll stay on that territory until the very end.”The females, on the other hand, are “kicked out by their mothers,” he said, and bounce around through the 100- to 300-acre territory looking for a single male, or a free cavity.

The black and white birds are about eight inches long and adult males have small patches of red feathers, or cockades, on both sides of their heads.

The birds work intensely not only building cavities for roosting and nesting, but also maintaining them and defending their homes from interlopers, anything from squirrels to screech owls to bats to honey bees. The cavities get passed down from father to son. If woodpeckers don’t inherit a cavity, they’ll look for one that’s been abandoned or one that’s unguarded.

Habitat Challenges

Historically, RCWs ranged in old-growth pine forests from southern Maryland and southeastern Virginia, through the North Carolina Coastal Plain and the Piedmont to southern Florida, to eastern Texas and southeastern Missouri. Today, the populations have been reduced to small, isolated populations in Florida and the Carolinas.

It’s remarkable that the very particular red-cockaded woodpecker, a highland species, has done as well as it has at the preserve, said J.H. Carter, owner of Dr. J.H. Carter III & Associates Inc, an environmental consulting company based in Southern Pines that has managed the woodpeckers at P3 since 1995 at an annual cost of about $124,000.

“The fact that the birds can survive there, and even increase their species, is highly unusual,” he said. “A lot of that habitat is so wet you can’t log it well.”

Although the pine forests in the region have been heavily logged, there are apparently enough centuries-old pines remaining for the woodpeckers in which to build their all-important cavities – and not just in P3. Carter estimates that there are as many as 60 groups of the birds scattered across the peninsula.

But a shortage of old pines to build cavities, losses to squatters and tree mortality from storms and pine beetles has been a serious problem at P3.

Carter’s company, which is updating the RCW management plan, has captured and marked the resident woodpeckers with leg bands. By looking through a spotting scope, the bird’s sex, age and movements can be determined by the colors on the band.

Over 15 years, Carter said, the consultants have surveyed the property and installed more than 100 artificial cavities to help the population grow or to replace those lost in storms. The cavities are created by using a chainsaw to make a hole for a bird box, or by using a special drill to make a cavity in the pine tree.

Carter said he and his staff of about eight go out in the summer months with machetes and chainsaws to clear paths to cavity trees. Sometimes, the spots are so wet, they have to wear chest waders. Each cavity is checked and surveyed and new birds are netted and banded. A population census of the groups is conducted. Sometimes the consultants work alongside the forestry service to do controlled burns.

“It’s a wild piece of land,” Carter said.

Although the Palmetto-Peartree Preserve’s population of RCWs, he said, is small compared with other sites in the state – Fort Bragg has 400 groups, for instance – P3 is important to the recovery of the species.

“In the northeastern North Carolina area,” Carter said, “they have the most of any property.”

Hammond, with Fish and Wildlife, said he has noticed in recent years that P3 has been looking increasingly unkempt, and he realizes public access there is not a priority right now for the DOT. But he has high hopes for the site.

“There’s potential for it to be a really keen eco-tourism destination,” he said. “It is a neat place to visit.”