MOREHEAD CITY – Some people spend their entire careers punching a clock, leaving work behind at 5 p.m. on Friday and not thinking about it again until 9 a.m. Monday. Patti Fowler was never one of them.

Fowler, who will be 60 in November, plans to retire this year as chief of the N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries’ Shellfish Sanitation and Recreational Water Quality Section. During her 30-year career protecting the public from the dangers of pollution, Fowler has earned the respect of her colleagues and helped direct and develop not only North Carolina’s shellfish regulations and procedures but also the federal rules that apply nationwide. She’s been a member of the Interstate Shellfish Sanitation Conference since 1986 and now serves as vice chair of the organization, which formed in 1982 to promote shellfish sanitation through the cooperation of state and federal agencies, the industry and the academic community. The N.C. Coastal Federation recently recognized Fowler with a Lifetime Achievement Award for her efforts to protect and restore coastal and shellfish water quality.

Supporter Spotlight

A native of Stratford, Conn., Fowler began her state job here on Jan. 1, 1983. Since then, she’s overcome personal challenges, including the death of her husband, George, in 1995, her own near-fatal heart attack five years ago and some of the struggles a single mother can face in a male-dominated profession. To Fowler, adversity has been a motivator.

“I’ve always wanted to do things the right way and that’s what drives me,” Fowler said. “Everybody has lumps in the roads they go through. It was tough but it makes you a stronger person. There’s always somebody who has it worse than you. I always tried to not bring personal things to work but just to be here today is to celebrate that and to try to be the best at everything. I have a strong belief in what we do and I always wanted to make North Carolina’s shellfish sanitation program one of the best in the country.”

Members of Fowler’s staff know all about her commitment. J.D. Potts is the recreational water quality program director at the agency, working alongside Fowler since 1989.

“She’s very dedicated, she’s a workaholic and she has an incredible drive,” Potts said. “I’ve seen her car here on Sunday mornings when I’m leaving church. She’s always emailing people or calling them on weekends. She loves protecting public health and she’s always looking after the interests of North Carolina and the public.”

Fowler credits her mentors, Bill Kirby-Smith, a marine ecology professor, and Richard Barber, professor of biological oceanography, at Duke Marine Lab in Beaufort where she previously worked six years. Kirby-Smith said Fowler demonstrated her abilities early on, as an undergraduate student at the Duke lab.

Supporter Spotlight

“When she was working for me, it was that she was thinking about what she was doing when she was doing it. Not everybody was like that. It was as if I had somebody with a more advanced degree working for me. Her brain was on the topic and she would notice things that were out of whack. And she got along well with people,” he said.

Fowler said she’s simply concerned about public health and the coastal environment.

“I live here and I like it because I know I can go out in the middle of the river and jump off my boat and not have a concern and I’m sure a lot of other folks feel that way. I mean, why do the tourists come here? It’s the beautiful beaches,” she said.

Now, as Fowler looks ahead to retirement and spending more time with her daughter Mary, 23, and grandson Wayne, 4, along with her other passions – gardening, cooking and boating – she sees years of work to protect the public is in danger of being undone as state lawmakers chip away at waterway protections developed over the past 30 years.

Sources of Pollution

During the early 1980s, researchers were just beginning to understand the links between coastal development, stormwater runoff and pollution of shellfish waters.

“Back then is when we started noticing that after a significant rain event, when we would go out and do our routine sampling, we would see some higher bacteria counts,” said Fowler.

The resulting shellfish closures were necessary because the bacteria can be harmful to humans. The federal government mandated state shellfish sanitation programs in 1925 after a number of typhoid outbreaks in the Northeast from tainted oysters. The programs began as cooperative efforts of the federal government, the states and the shellfish industry. All coastal states have guidelines, from how to classify shellfish waters to how the product is harvested to temperature control during transport.

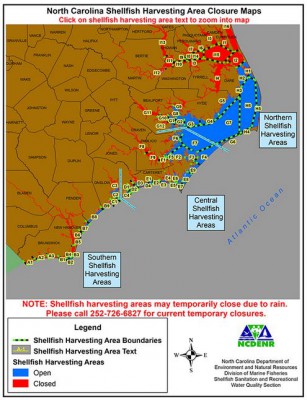

“Oysters, clams and mussels – molluscan shellfish – they’re filter feeders, so the waters that they come from have to be exceptionally clean. As far as water quality standards, shellfish harvesting is probably your highest standard,” Fowler said.

In the early 1980s, water quality problems were an emerging issue in North Carolina. Pollution of shellfish waters was affecting human health and the resulting closures of shellfish beds were hurting the coastal economy. That’s when state officials hesitantly began discussing ways to address coastal stormwater. Those efforts faced immediate opposition. Then in 1983 came the first statewide shellfish closure after a storm dumped large amounts of rainfall early that year. Fowler said the storm changed how her office operated.

“That’s when we started doing what we call our ‘conditionally approved’ classification – areas or waters that are good most of the time. Rather than close them we came up with a plan, when they are good, to allow harvest,” she said. “It gave us a way to be able to utilize the resource yet still protect public health.”

The General Assembly, also that year, approved funding to provide “intense monitoring” of polluted shellfish waters and open these areas, on a temporary basis, when the waters and shellfish conform to standards. The provision increased shoreline survey activities in order to eliminate sources of pollution with the goals of improving the plight of commercial fishermen and reducing the potential for poaching when the areas were closed.

The data collected showed coliforms in coastal waters were mainly from impervious surfaces on land, and stormwater was the main way for that pollution to reach shellfish waters. The results became predictable over time, down to the fairly precise amount of rainfall where levels of bacteria exceed standards.

“We know that an inch of rain, for instance, say in Newport River, is going to increase those bacteria counts above the standard so we close it on a temporary basis rather than permanently close it,” Fowler said.

Sharing Data

The fledgling N.C. Coastal Federation, and its founder Todd Miller, saw the data collected by Shellfish Sanitation surveys in the 1980s as useful in showing the connections between development and declining water quality. The federation fought business interests and government bureaucracy to push for improved stormwater management.

Fowler’s agency later partnered with the Coastal Federation on a wetlands-restoration project at North River Farms in Carteret County with federal funding.

“Our little part of that was to come up with a new shoreline-survey methodology that was easier to share with the agencies that might could use that data,” Fowler said.

Now, those surveys continue and with the aid of geographic information system, or GIS, and other computer technology. All potential pollution sources – marinas, point-source discharges, malfunctioning septic tanks, large concentrations of animals, dog pens on the shore – are now mapped and in digital form. In addition, Fowler said sanitary surveys of all growing areas include water sampling, a bacteriological survey, hydrographic studies and weather observations, especially related to rainfall and flooding. The entire N.C. coast is now mapped using the system and regular surveys keep the maps up to date. The data is now available online.

Emerging Regulation

Developers and others fought to keep stormwater regulations at bay, and it wasn’t until the late 1980s that rules began to take shape in North Carolina. Despite claims that the limits were too restrictive and would halt economic growth, coastal real estate development soared and the population in Eastern North Carolina far exceeded projections during the 1990s.

More development means more impervious coverage, but what can be gleaned from shellfish sanitation surveys?

“To make a determination on trends through the years, I see that we have more areas that we close after rain events now than we used to,” Fowler said. “They may be wider in range, they may be areas that we didn’t close in the past and the only thing I can attribute that to would be additional stormwater runoff.”

Still, the information collected and the closures of shellfish waters don’t always provide a clear picture of the pollution problem and that has fueled continued efforts to weaken stormwater regulation, including regulatory “reforms” debated in the 2015 legislative session.

“I remember the first stormwater rules that came up in 1989 and then it came up again in 2009. At that point the Division of Water Quality and DENR (Department of Environment and Natural Resources) were looking at a 12 percent impervious limit and, of course, the shellfish data, using it as a way to show that, yes, stormwater runoff does affect water quality,” Fowler said.

Fowler said the current fight is a replay of previous battles, and those working to undo existing rules are ignoring the science.

“Knowing that stormwater runoff is the biggest problem that we see with degradation of water quality, why increase the imperviousness along the shoreline to degrade our water quality? It just doesn’t make sense,” she said. “By implementing that 12 percent doesn’t mean we were going to get better, it means we were going to maintain.”

Brunswick County has been one of the fastest-growing counties in the state during the past 20 years and about 65 percent of its shellfish waters are now permanently closed. But the correlation between growth and closures isn’t always clear, Fowler said. Permanent closures aren’t increasing at the same pace as development, possibly because of proper management.

“Looking at our data you might think that everything has been copacetic forever because you’re not seeing these increases in the permanent closures, because if we can manage those waters on a temporary basis, and close them temporarily, we’re not losing the availability of the shellfish resource to the harvesters when it is good,” Fowler said.

Expanding Roles, Shifting Agencies

Up until the late 1990s, the state wasn’t doing any type of water testing for bodily contact or swimming. Then-Gov. Jim Hunt directed Shellfish Sanitation to sample for recreational swimming, with temporary funding in 1997. Two years later the funding was made permanent. Then, in 2000, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency required states to sample for swimming.

Until 2011, Shellfish Sanitation was in the state Division of Environmental Health in DENR. Then the division was abolished and all its sections were moved to different agencies.

“Our section was moved to the Division of Marine Fisheries – a really good fit,” Fowler said, adding that at that point, all shellfish dealer certifications, sampling, proclamations and enforcement were together under one department.

Until last year, Shellfish Sanitation operated three offices, Nags Head, Wilmington and Morehead City, to monitor coastal waters and a Greensboro office to monitor shellfish transport west of Interstate 95. In 2014, state budget cuts led to the closing of the Nags Head office. As a result, the department closed all waters in the upper Pungo, upper Pamlico and upper Neuse rivers, more than 300,000 acres, on a permanent basis.

“I didn’t have the lab up there or the staff,” Fowler said, adding that the northeast was not a productive, commercially harvested shellfish area. With no monitoring and no sanitary survey, shellfish areas must remain closed to harvesting.

“Personally, I think it’s a shame we don’t monitor them so we know what’s going on there, getting an overall idea of what our water quality is really like,” Fowler said.

The loss of Nags Head also meant the number of recreational swimming sites sampled had to be cut.

“As a manager working for state government, we have to give something up, but I always hate when we have to cut public health. That’s always been tough.”

Fowler credited her team, including Potts, Andrew Haines and Shannon Jenkins, in helping her successfully manage through the budget cuts.

“I have this incredible staff that will step up and just do it. Maybe it’s when you’re in public health you have a real desire and you see the good in what you do. You’re responding daily to a number of environmental things. They’re here. We’re all here. It doesn’t matter if it’s New Year’s Day, whether it’s a Sunday or a holiday, we’re in here to work on a proclamation to reopen an area so that guy can get out and work tomorrow. And they’re all that way, from my administrative assistant to the lab techs to the water samplers. We can’t just go home on Friday and forget that it rained Friday night. We still have to get up Saturday morning and close those waters.”