I’m sitting on wet sand inside of Cape Lookout Bight. A pair of 10×42 binoculars rest upon my knee, and the sun has just dipped below the horizon. An artist’s palette of pastel color unfurls across the sky with perfect symmetry reflected in the waters below. This is the kind of idyllic postcard moment that marketing wizards conjure up for would-be tourists across the Northeast. Serenity. Romance. Beauty. They would probably have a couple glasses of red wine strategically placed in the composition. But there is one small detail from this scene they would certainly leave out of the story: the fact that I’m watching the dorsal fin of a shark ply the waters just feet in front of me.

Sharks dominated the national news throughout the month of July thanks to a slew of attacks along the coast of North Carolina this summer. Speculation has run wild, of course, and stories ranging from perfect storm scenarios to exploding populations have made it into the media. As one researcher from UNC’s Institute of Marine Science explained to me, however, “most of those reporting on these events are unburdened by actual facts.” Whatever those facts may be, the bombardment of all things sharks in the media has culminated in this moment for me right here, right now, on a secluded beach at dusk hanging out with predators.

Supporter Spotlight

In all honesty, I have no idea what species of shark it is cruising these shallows at dusk. I just know that compared to the three others I see, this is the largest. Judging from the distance between its dorsal fin and tail, I estimate its length at about 5 feet. For the uninitiated, this may seem large, but in reality, it’s not.

Along our coast, big sharks, or what researchers call the great sharks, can range from 6 to 20 feet in length. These are the top dogs if you will, the apex predators of our corner of the blue wilderness we call the oceans. Most have names that you know: names like hammerhead, tiger and bull, to list a few. These are the sharks that make headlines, the ones kids go crazy about at aquariums, and the sharks that now face the immediate possibility of extinction – an inconvenient fact that was largely absent from the media feeding frenzy.

For more than four decades now, the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City has been engaged in the longest-running study of sharks in the United States. From spring to fall, every two weeks, a small team of researchers travel off the coast of Shackleford Banks to catch sharks. Soaking longlines like commercial fisherman, the biologists are able to capture a multitude of different species that are feeding at various depths in the water column. This location is ideal for getting a snapshot of what is going on along the coast as it sits within something of a bottleneck along the sharks’ migratory range. In other words, the data collected here can give us an understanding of shark populations from Cape Cod to Cape Canaveral. And there are 43 years’ worth of data to back it all up.

The results? Harrowing. Populations of great sharks across the board have collapsed: sandbar sharks, 87 percent decline; blacktip sharks, 93 percent decline; tiger sharks, 97 percent decline; scalloped hammerheads, 98 percent decline; and bull, dusky and smooth hammerhead, 99 percent declines. Another long-term study out of Virginia concludes that sand tigers have also declined by 99 percent.

Keystone Species

This a problem for us – let alone the sharks. You see, the great sharks are keystone species. Their presence impacts entire marine ecosystems through a process that conservation biologists call trophic cascades. It’s kind of like Ronald Reagan’s trickle-down economics – only this actually works.

Supporter Spotlight

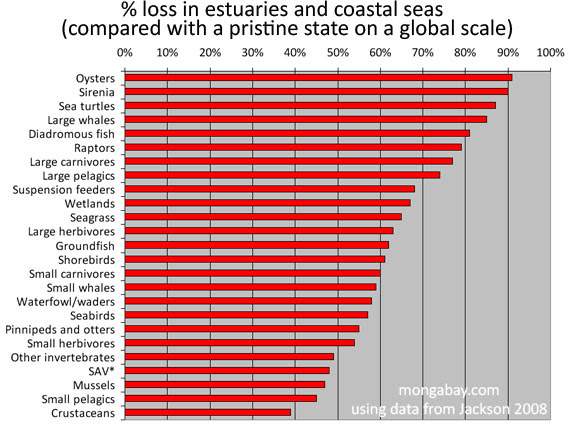

Researchers in 2008 studied the widespread decline of sharks in the northwest Atlantic Ocean, which led to what is called a “trophic cascade.” The loss of top predators causes population changes down through the food chain. The loss of sharks triggered a rapid rise of cownose rays, which feed on oysters and clams. The clam fishery collapsed as a result. A trophic cascade can run all the way down a food chain, leading to drops in zooplankton and rises in phytoplankton, changing the ecosystem entirely. Chart: Mongabay.com

Picture a pyramid. At the top sits the shark, the apex predator. Below that on the next trophic level sits the shark’s main prey species. In this case, along this coast, that would be species including the cownose rays. These are what we call mesopredators. The next level down hosts the prey species of the rays. This keeps going until you make it to the very bottom of the food chain and you reach those species that obtain their energy directly from the sun. This is a trophic pyramid, a simplified depiction of the ecological pecking order. Big sharks eat rays, rays eat scallops, clams and oysters, and the bivalves in turn filter water in our estuaries.

So, what happens when you chop off the top of the pyramid?

Some 2,500 miles northwest of here is the greater Yellowstone ecosystem, and a landscape that has quite famously answered this very question. The national park that makes up the heart and soul of this place has been something of a test tube for scientists to observe and study for well over a century now. Shortly after the inception of the world’s first national park, its new managers waged a full-scale war against the apex predator of that ecosystem – the wolf. And within a few short years, the big canines were effectively wiped off the map.

For the next century, park officials watched as elk populations began to explode. This was seen as beneficial at first. People liked the elk. More elk therefore meant more of what people wanted. Hunters in the surrounding national forests were elated. But then aspen stands began to die. Willow stands that ringed the wetlands disappeared. Beaver disappeared. And the temperature of some streams and creeks began reaching levels that could not support fish in the summertime. In essence, the very fabric of an entire ecosystem began to slowly fray and unravel.

No wolves in Yellowstone equated to an unchecked population of antlered eating machines on the landscape. Favorite meals for this species are aspens and willows which predictably began to disappear. All of those grassy meadows that you see today with lazy creeks running through them are the result of overgrazing by elk. There should be willows in there. There should be beaver ponds, stands of aspens. As these critical species of trees and shrubs began to disappear, so too did the species that depended upon them such as the beaver. And beavers, more so than any other animal in the northern Rockies, create home and habitat for a multitude of other animals ranging from waterfowl to moose.

Sharks are the apex predators of our coastal ecosystem. They are the wolves of the sea. Eliminate these animals from the trophic pyramid and you release the mesopredators like cownose rays from the checks and balances that sharks once placed on their population through predation and fear. As a result, much like the increase in elk populations across Yellowstone, we have witnessed an explosion in the cownose ray population along the eastern seaboard. That population is now estimated at around 40 million. And it takes a whole lot of bay scallops to feed all of these rays.

In 2006, after 100 years, North Carolina’s commercial scallop fishery – the second largest in the nation – was shut down. The reason? There were simply not enough scallops in the estuaries to support it. When the cownose rays migrated through the area, they were consuming almost every adult scallop that they could find. The rays’ effect on the scallops was confirmed by setting up palisades made from PVC pipe around certain scallop beds designed specifically for excluding cownose rays from the area. After a two-year hiatus on harvesting scallops, the fisheries reopened, but barely. And even today, this fishery remains precarious at best.

This is quite possibly just the tip of the iceberg. The population collapse of great sharks in the western Atlantic has occurred primarily within the last 20 years due to commercial longline fishing and the rising demand for shark fin soup. It takes time however, even in a terrestrial ecosystem, for the effects of these sorts of system-wide changes to take shape.

And this is a marine ecosystem we are talking about, one that’s hidden beneath the surface of the water, where we cannot so easily see such changes as they begin to take place. In Yellowstone, anyone could look out across the Lamar Valley and see the lack of willows and aspens. In the ocean and estuaries, it takes teams of specialized researchers working in the water and scores of number crunchers to mine through fisheries data. And the data does not always point to the same thing.

I had the opportunity to chat with Dr. Stephen Fegley, a marine ecologist from the Institute of Marine Sciences about the data that is currently available. Fegley has been pivotal in analyzing all the numbers from the university’s study on sharks, and if anyone could help explain the discrepancies between fisheries’ and researchers’ data that I was seeing, he was the guy.

“The most important thing that you have to understand about the institute’s study is that it is 43 years old. This is the longest-running study of sharks in the United Sates,” said Dr. Fegley. “Populations fluctuate naturally, and with so many variables, it’s impossible to determine a trend in a population without years of data. This is why UNC’s work is unique. It is looking at specific species over a long period of time.”

The N.C. Department of Marine Fisheries recently released its statistics for the 2014 commercial fishing season. Shark catches were up, way up. In 2013, commercial fishermen brought in an estimated 500,000 pounds of shark from N.C. waters. In 2014, it was double that – tipping the scales at over a million pounds. Such information can be read different ways. For some, this 2014 data could indicate that shark populations were getting healthier and species were rebounding along our coast. But when it comes to statistics, the devil is always in the details.

You see, NCDMF published data doesn’t actually differentiate between species of shark except for the two species of dogfish that are caught commercially. That 1 million pounds of shark says just that: shark. What kind of sharks? Black tip? Tiger? Great White? The prehistoric Megalodon? There is no mention.

Much of the shark fishery tends to take place out near the continental shelf – except for those who are targeting sandbar sharks for their fins, which is only illegal in the United States if they don’t bring the entire shark back to the dock. The shelf is the realm of pelagic sharks such as blue and mako (a species found in many fish tacos). These species are open-ocean sharks. They are not the ones that fall under the coastal complex of species that the Institute of Marine Sciences is ultimately targeting. And they are not the species that function as apex predators in our coastal waters.

Commercial fisherman know the species of sharks that are in question quite well. They have to. Their licenses depend upon it. There is a complete ban on fishing for most of these big sharks. For example, sand tiger sharks (down 99 percent) have been banned since 1997. Dusky sharks (down 99 percent) have been banned since 2000. And the scalloped hammerhead (98 percent) is on the endangered species list.

The majority of the great sharks are all now on a commercial “do not touch” list. But longlines are just that – very long lines. Some stretch for miles and contain many hundreds of hooks. This method of industrial fishing catches fish indiscriminately. Though a commercial longliner may be targeting mahi-mahi or tuna, everything from sharks to sea turtles are caught incidentally and then labeled as by-catch. Some species of sharks can be kept and sold on the market. Others, such as the ones above, are tossed overboard. And by the time these sharks have been landed, they are typically already dead. So regardless of federal bans and even the Endangered Species Act, these species of sharks continue to slip over the edge of oblivion.

Back in the estuaries, as scallops become scarce, cownose rays turn to oysters and hard clams — the stuff in your clam chowder. Our estuaries are already in a state of recovery from the over harvesting of oysters, and millions of dollars are being spent on restoration here. What happens when cownose rays begin focusing on these oyster beds? It is this very question that has sparked the “Save the bay, eat a ray” campaign in Virginia.

And the cownose ray is just one species, the one that we know about simply because it has had an immediate and direct financial effect upon the livelihoods of watermen across our coastal plain. What other ripple effects will the disappearance of these great sharks have across our marine and estuarine systems? We simply don’t know yet.

Those of us who live at the edge of the sea, teeter upon the precipice of the greatest wilderness on our planet. Right here, beneath the waves, is the Serengeti. Apex predators stalk the shadows. Food webs here have a 400-million-year-old history. New species are still being discovered on a regular basis and not just strange microscopic stuff. New species of megafauna are still turning up – such as the Carolina hammerhead, which was announced in 2013.

Our world is inextricably linked to the health and wealth of these oceans. From the oxygen we breathe, the climate we live in and the food that we eat. Yet, we know more about the dark side of the moon than we do this blue wilderness.

Sometimes, it’s all too easy to lose ourselves in the argument of conservation based solely upon anthropocentric desires. What is good for us? What do we want? How do collapsing populations of sharks affect us? And all of this without consideration for what may simply be best for the other members of this planetary community we call life on Earth. We are a species that stumbled upon godlike powers, but never learned how to responsibly wield those powers. We make decisions as to which species shall live, and which shall be slated for extinction with only our own self interests in mind.

For most of us, the question of whether or not great sharks will go extinct seems to be beyond our control. With ethics and morality considered, we wrinkle our brows at the notion and feel frustration, maybe even anger, toward those that we assume are the ones that wield such control and yet allow for this to happen. But if we peel back the layers of excuses and look at the issue for what it really is, we find ourselves staring into a mirror. We are the ones who wield that power. Only, we do so with our wallets and how we chose to spend our money. As long as we create the demand, industry will continue to supply. And that demand currently kills 100 million sharks a year.

As Walt Kelly, the creator of the “Pogo” comic strip, so poignantly revealed to us all, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”