MANTEO – Sen. Richard Burr sent some of his people to the N.C. coast a few weeks ago to get a feel for what locals think about the prospect of offshore drilling. In Dare County, they got an earful.

Lee Nettles, the executive director of the county’s Visitors’ Bureau, was among the 20 or so local people invited to meet with Burr’s aides. He sat at a long conference table along with county commissioners, mayors, tourism and chamber of commerce officials and members of environmental groups. No one supported drilling.

Supporter Spotlight

Why? Nettles brought up the specter of an oil spill, like the one then ongoing off the California coast. “If that were to happen here, we’d become a wasteland,” Nettles told the visitors from Washington. “We don’t think offshore drilling is a smart risk.”

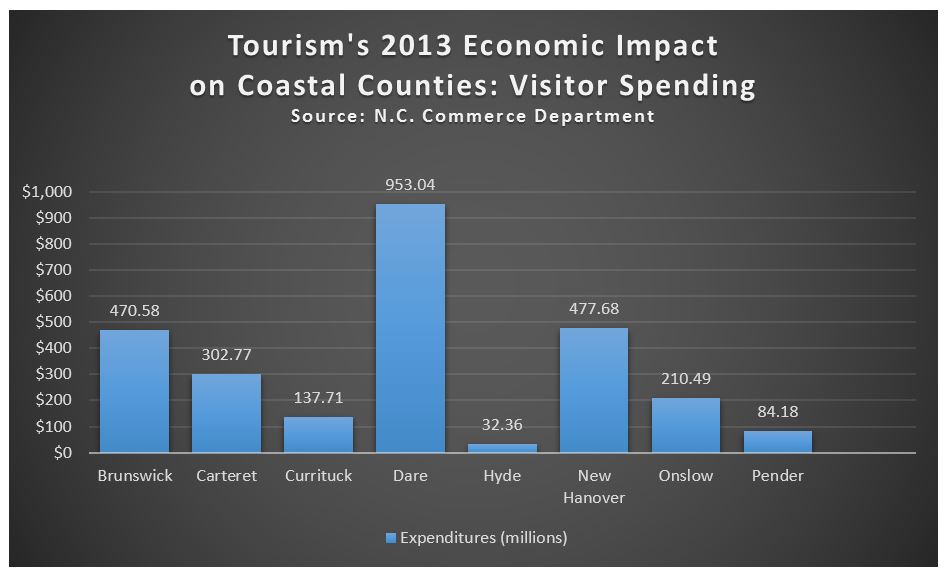

The fear of what an oil spill might do to the coast’s tourism industry is at the center of much of the opposition among local governments. In North Carolina, from the Outer Banks in the north to Sunset Beach in the south, beaches and coastal towns draw more than 11 million visitors each year. In 2013 alone, visitors spent just shy of $3 billion in the eight oceanfront counties, according to the state Department of Commerce.

Almost 20 cities, towns, counties and tourism agencies along the coast have passed resolutions against drilling or it’s kissing cousin, seismic testing.

Include the Dare County commissioners and every town in the county on that list. “The tourism board passed five resolutions opposed to drilling,” Nettles said. “It’s no secret where we stand.”

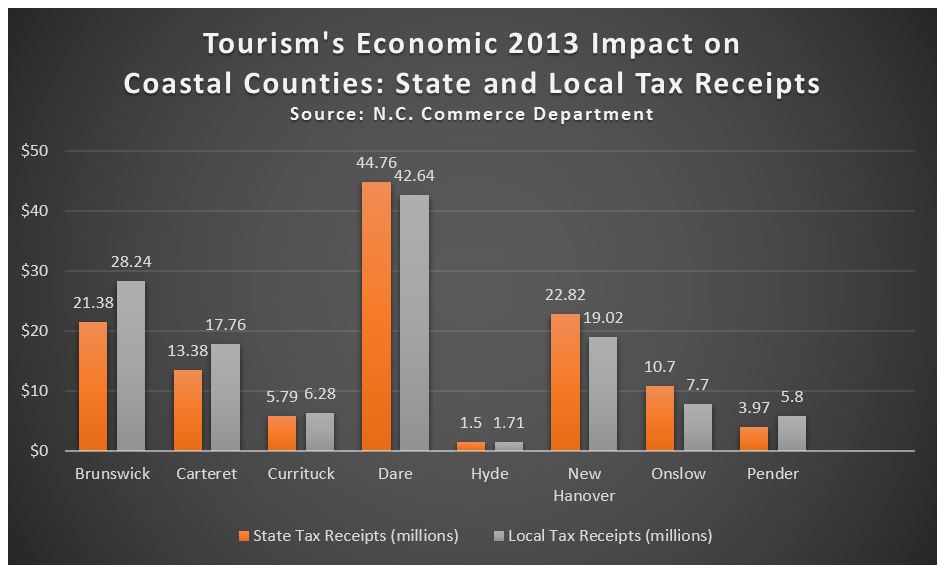

And it’s not hard to figure out why. If coastal tourism were the Internet business, Dare would be the Google of the coast. Tourists spent almost a billion dollars in the county in 2013, according to state figures. That’s more than double what was spent in Dare’s closest coastal competitors, New Hanover and Brunswick counties. Local governments in Dare received almost $45 million in sales taxes that year, again far outdistancing other coastal counties.

And it’s not hard to figure out why. If coastal tourism were the Internet business, Dare would be the Google of the coast. Tourists spent almost a billion dollars in the county in 2013, according to state figures. That’s more than double what was spent in Dare’s closest coastal competitors, New Hanover and Brunswick counties. Local governments in Dare received almost $45 million in sales taxes that year, again far outdistancing other coastal counties.

Supporter Spotlight

That’s real money, Nettles told the Burr people, not the estimates that the oil industry and its supporters like to use. If drilling were allowed off the coast, an industry study done in 2013 estimates that oil and natural gas production would have a statewide economic effect of $1 billion to about $5 billion annually by 2035, depending on how much is produced and the prices it sells for. The median estimate is just shy of $3 billion.

The economic impact of tourism in those eight ocean counties will be worth almost $4.5 billion a year by 2035, Nettles noted at the meeting.

Tom Bennett, the mayor of Southern Shores, spoke for everyone around the table. “It would be a tragedy to throw all that aside for the interests of offshore drilling,” he said. “I don’t think any of us support this.”

Warren Judge, a Dare County commissioner, agreed. “The risk-reward just isn’t there,” he said. “You can’t look down the path and see at any point an amount of revenue that would compare to what tourism will provide over the next decades.”

In Carteret County, municipalities including Beaufort and Emerald Isle have passed resolutions opposing offshore oil exploration. Other towns and agencies here have shied away from stating a position, due in part to the prickly politics involved.

Visitors to Carteret County spent nearly $303 million in 2013, according to the N.C. Commerce Department. Those expenditures generated $13.38 million and $ 17.76 in state and local sales taxes, respectively.

Visitors to Carteret County spent nearly $303 million in 2013, according to the N.C. Commerce Department. Those expenditures generated $13.38 million and $ 17.76 in state and local sales taxes, respectively.

The Carteret County Tourism Development Authority has yet to formally oppose offshore exploration. The authority discussed taking a position as early as 2008, but members of the board at the time chose not to vote to approve a resolution proposed by then-chairman Art Schools stating that offshore oil exploration and drilling would be acceptable as long as it doesn’t impact tourism. Board members said at the time the oil industry would not be in the best interest of coastal tourism.

More recently, the TDA has been asked again to consider a resolution, this time firmly opposed to exploration and drilling, but Director Carol Lohr said Thursday TDA board members have expressed concerns that it’s too early to take a firm stance and more information is needed. That said, there is consensus that tourism must be protected.

“From the comments I’ve heard, we would never support anything that would harm the tourism industry in any way shape or form,” Lohr said, adding that, based on past accidents such as the Exxon Valdez and the Deepwater Horizon, N.C. beaches would take years to recover from a spill of that magnitude. “This county is so dependent on tourism that we can’t afford to risk that, even if it’s a minimal risk and I don’t think anyone can guarantee that.”

At the statewide level, North Carolina broke its tourism records last year, Gov. Pat McCrory announced earlier this month, with domestic travelers spending a record $21.3 billion in 2014, a 5 percent increase over 2013. State figures show that tourism in 2013 supported more than 3,000 jobs, with a payroll of $52.9 million in Carteret County, home of Morehead City’s state port. In New Hanover County, home to the state port in Wilmington, comparable figures the same year were more than 5,000 jobs and more than $105 million in pay.

Although some in the immediate aftermath of Deepwater Horizon predicted as much as a 33 percent decline in tourism along the Gulf for an extended period, and 2010 was filled with reports of nearly empty hotels and motels and heavily impacted restaurants and retail businesses, it was by no means uniform. New Orleans, for example, received $5 million of $15 million in tourism-marketing money BP gave Louisiana to counteract negative publicity from the spill, and the city used that money to advertise that it was 100 miles from the spill. And 2010, according to Louisiana figures, turned out to be New Orleans’ best year since Hurricane Katrina five years earlier, with 8.3 million visitors in the second half of the year alone.

By 2011, by most accounts, the visitors were back, with Florida’s Panhandle beaches reporting numbers up 61 percent over 2010, and Alabama up 51 percent and Mississippi 7 percent. Some attribute the rebound to ramped-up tourism marketing in the months following the BP spill.

One town councilman in Kure Beach, Emily Swearingen, was so concerned about the potential impact of an oil spill that she went to Congress on April 15 and testified to the U.S. House Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources during the same session that McCrory appeared and pushed to move the 50-mile buffer in to 30 miles, and for the feds to share oil revenue with the state. McCrory noted that Kure Beach Mayor Dean Lamberth had supported, by letter, offshore energy development, but Swearingen said that letter didn’t reflect the feelings of the townspeople.

She said in early May that on Jan. 27, 2014, more than 300 residents turned out for a town meeting in protest of the mayor’s letter.

Any significant decline, even short-term, in tourism revenue, she said, would severely impact the town.

Sales tax and occupancy tax receipts, she said, help pay for street maintenance, police and fire service, among other things, in Kure Beach. The municipality shares Pleasure Island with another town, Carolina Beach, and together, they generate more than $120 million a year in income. Another $11 million comes from charter and head boats and seafood processing and packing, which also would be impacted if oil were found in the area offshore and an accident occurred.

“People would lose jobs and homes and businesses,” she said. “We can’t afford that. It just isn’t worth the risk.”

A relatively small accident – like the four-mile-long oil strip on the beaches of Santa Barbara, Calif., after an onshore pipeline burst two days before the Memorial Day Weekend – would cause significant hardships, and a Deepwater-scale disaster would cause incalculable harm.

There’s also historical basis for this concern. The red tide in 1987, some say, might be an instructive case. The dinoflagellate algae bloom came in on Halloween day that year, swept north from the Gulf off Florida, where red tides are common.

The algae, first spotted in Emerald Isle on the central coast, eventually forced the closing of more than 350,000 acres of shellfishing waters from Hatteras Island to Calabash, near the South Carolina border. The problem persisted for more than six months, to varying degrees in varying locations. An estimated 9,000 commercial fishermen were out of work, and figures prepared by the state for disaster relief estimated $4.5 million in losses by December.

In addition, official estimated hotels and motels, big and small, during this peak fall fishing season, lost $200 to $2,500 a day; restaurants, $200 to $1,800 a day.

Brad Rich, Frank Tursi and Mark Hibbs contributed to this report.