This weekend is the traditional start of the tourist season along the N.C. coast. Millions of people will flock to the state’s beaches this summer. The first tourists of the 19th century sought the ocean shore for a different reason. They went to escape death.

Down here, we have an overabundance of three things: sweet tea, sunshine and mosquitoes. Each one has played no small part in shaping our culture and communities – for better and for worse. From the lines etched into our skin that map out the stories of lives lived in the out of doors, to the too sweet iced tea that seems to define the boundaries of the diabetes belt, this is the South and all that that means. But sweet tea and too much sunshine are, to a degree, lifestyle choices that come with the culture. Vampires however, are inescapable.

Supporter Spotlight

It was a full day’s sail across the Albemarle for Francis Nixon and his family. Even with the southwesterly blow that filled his sails, traveling this inland sea was often times little more than a gamble with one’s life. Pocked with shoals, oyster beds and remnants of a long ago drowned forest, the Albemarle was a saline gauntlet, and the weather here was notoriously unpredictable. This stretch of water was very much an extension of the Graveyard of the Atlantic — though such a name would wait another 120 years to be coined.

Stepping out onto the amber colored sand of the barrier islands at a little village called Nags Head, Francis drank of the salt infused air that rushed in from the ocean. This was why he was here, the first of his kind really – a well to do Carolina planter on the barren barrier islands in search of refuge for himself and family, in search of the salt air.

As author Karen Blixen would one day write, “The cure for anything is salt water: sweat, tears or the sea.”

Season of Sickness

And for early 19thcentury planters such as Francis Nixon, he was desperate for a cure, for relief, for an escape from the “fever and agues” that plagued the mainland this time of year. The sea air, Francis Nixon hoped, would pick up where prayers left off.

Summer was the season of sickness, an annual event that swept through the towns and plantations all across the South. People spoke of the “seasoning,” that first summer in the Carolinas that would determine if you would live or die. Those that survived their first round of fevers would push on, most likely suffering again in the future but not fully on their death bed. In his journal, Johann Schoepf wrote in 1784 that, “Carolina in the spring is a paradise, in the summer a hell, and in the autumn a hospital.”

Supporter Spotlight

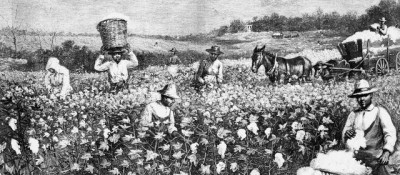

Across the Albemarle, back on the mainland, the heat of summer mixed with the oppressive humidity as slaves, servants and those of lower castes toiled in fields of rice, cotton and tobacco. By day, sounds of cicadas could be almost deafening, and eyes burned from sweat in temperatures that could reach triple digits. Most often, only night fall brought relief to the land. But as the sun began to set, and temperatures subside, the dark brought with it another type of hell – the incessant onslaught of mosquitoes.

The year was 1830. Air conditioning was not yet invented. Screens were nonexistent at this time, as was the understanding of mosquitoes as vectors of disease.

The Age of Disease

The age of exploration and imperialism had ushered in a different age, as they always seem to do in the pendulum swing of action and reaction. This one, historian Alfred Crosby christened the Columbian Exchange. As ships hailed from ports from all sides of the Atlantic, animals, crops, insects and diseases jumped oceans and continents. Within a few hundred years a new Pangea was underway as species mixed across the globe in ways that had not been possible for roughly 175 million years. When it came to many of these species, their forced relocation came at the whims of commerce and trade. But others, such as pestilence and disease, stowed away in the blood of passengers and cargo.

Slavery, that most nefarious of institutions, brought with it countless horrors. But of all these horrors, the one that was least expected and goes generally unacknowledged today was the presence of a unique and distinctly African strain of pathogen coursing through the veins of many would be slaves that survived the voyage to the new world; a pathogen that had grown up alongside of humans in Africa, and one that was locked in a deadly race with human evolution. Those unfortunate souls who found themselves in shackles and stuffed deep into the bowels of the hell that was a slave ship, had either survived the seasonings as a child in Africa or had one of several unique genetic mutations found in the genes of their region that imparted immunity to the effects of this disease. But for those of European and Native American ancestry, their blood and livers were virgin territories unequipped for handling the likes of Plasmodium falciparum – the most deadly and virulent strain of malaria on the planet, and a disease that even to this day continues to kill one million people worldwide on an annual basis.

Parasites like malaria tend to coevolve with specific host species for different stages of their life cycle. Basically, this particular strain of malaria needs both female Anopheles mosquitoes and humans to survive. Upon arriving to the shores of the colonial South in the blood of slaves, the Plasmodium parasite found both uninfected humans, and a species of mosquito that fit the criteria. In short order, the disease would spread like a wildfire from Virginia to Florida and west to encompass the Gulf States.

Carolina planters like Francis Nixon had no way of knowing that there was a connection between mosquitoes and the sickness and death that they watched sweep over their communities each summer. They could only make generalizations, associating the sickness with a season and understanding that it was worse around the swamps that so defined this landscape.

The leading theory at the time was that the sickness was caused by “miasma,” a sexy sounding word that has long since fallen out of use. Miasma is basically a stench or smell considered to be negative and potentially unhealthy. And this notion that these seasonal fevers were caused by bad smells coming from lowlands has a very long history that dates back all the way to the early days of Rome, which suffered the burden of its own unique strain of malaria – Plasmodium vivax.

It was from Rome that we inherited the name malaria. Originally this was not one, but two separate words: mal aria, or quite literally, “bad air.” And it was this “bad air” or miasma down in the lowlands around what would one day become Rome that allegedly prompted Romulus, the city’s founding father, to build atop seven hills so as to escape the pestilence associated with the low country.

The Scourge of Malaria

Malaria has been shaping our existence, patterns of settlement and cultures since the very origin of our species. So when Francis Nixon set foot upon the Outer Banks that summer of 1830 in search of respite from the miasma and ensuing fevers of summer on mainland North Carolina, he was doing exactly what western civilization had always done, he was searching for clean air to breathe.

Nixon and his family are believed to be the first of the Carolina planters to look east towards the Outer Banks to escape the malarial fevers that plagued the mainland. With the knowledge that the area known as Nags Head was generally free of sickness, he procured a 200-acre plot for his family’s summer time retreat near the base of Jockey’s Ridge. Word spread quickly to the other Perquimans plantations of the healthy climate and disease-free respite that he had discovered on the ribbon of sand off the coast. And by 1838 the first official hotel was opened in Nags Head to accommodate those well-to-do families that could afford to step away for a few months each year to escape the sickness that had come to define the South and its people.

It is difficult for us to truly wrap our minds around the effect that malaria had upon the Southern states. This is a disease that was officially eradicated from American soil in the 1950s. Generation after generation has been born into a world where such a disease is one that only inflicts the tropical Third World – certainly not the affluent “West.” But before the discovery of the connection with mosquitoes in the 1890s, death tolls in the South were identical to what we see today in sub-Saharan Africa.

Actual statistics are tough to come by for this time period unfortunately. Many deaths are directly attributed to malaria. Others simply to the symptoms. And then there are those that went unreported all together. In all though, probably one out of ten people succumbed to this disease every year.

During the Civil War, for which meticulous numbers were kept, an average of 10,000 Union soldiers died each year from the malarial fevers they contracted while fighting in the South. Even into the next century, Henry R. Carter, senior surgeon for the United States Public Health Services, in 1913 wrote in his report, Malaria in North Carolina, that people in tidewater North Carolina could not survive to the age of 30 here unless they were able to acquire significant immunity to the disease. The plague of malaria was so pervasive that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was established for the sole purpose of controlling and eradicating this disease from the South, which is why it is based in Atlanta instead of Washington.

A Resort Is Born

The trend that Francis Nixon and his family began would steadily pick up steam and momentum as the century wore on. From an unknown and practically non-existent hamlet tucked in behind towering sand dunes, Nags Head grew into the premier summertime resort community of North Carolina – rivaled only by Asheville, which also traces its rise in prominence to wealthy planters escaping malaria down below. Boardwalks were built, and grand hotels were erected. Horse races were organized and all manners of entertainment were brought in, built or planned to keep North Carolina’s landed gentry occupied and happy while on the island, laying the groundwork for the type of resort destination that Nags Head would come to be known for into the 21st century.

Today, the Outer Banks is one of the United States most sought after vacation destinations. Each year millions of visitors flock to the coast of North Carolina making tourism here a multi-billion dollar industry. Much like the aristocracy of the antebellum South that Nags Head began catering to 185 years ago, these people come for the rejuvenating effects that days spent with toes in sand and lungs filled with salty air has upon a person. Though the fever and sickness of malaria may no longer be the driving force of this need for escape, the debilitating effects of corporate-wasting syndrome and DNA-mutating impacts of a life spent overworked, over tech’ed and overstressed have proven to be just as powerful motivators.

Driving along N.C. 12 past Jockey’s Ridge and Kitty Hawk Kites, you can see the remnants of this time long since passed in the architecture of the ocean front homes. Here, you will see a line of houses quite unlike mansions that have come to typify ocean front property of the Outer Banks. Weathered, bleached from the sun and seasoned by salt, many of these houses date back over 100 years. The unpainted aristocracy, they are called. And they stand as a window into a history long ago forgotten.