First part of three parts

EAST LAKE — While the ocean is knocking at the front door of some beachfront homes and hotels in North Carolina, the forests across the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds are retreating from the shoreline.

Supporter Spotlight

They’re being driven back by saltwater. It’s seeping into the soil and surface waters of the coastal plain. What scientists call “saltwater intrusion” has been going on since the oceans began rising when great ice sheets started melting 20,000 years ago. But salt’s slow movement inland has accelerated in recent years, those scientists say.

They also say it has the ability to transform freshwater landscapes long before they are permanently drowned by the rising sea. The locals know this intuitively.

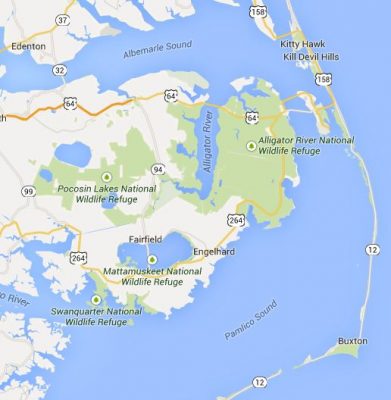

Just ask Scott Lanier, manager of Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge – the refuge sits on the eastern tip of the Albemarle-Pamlico peninsula, which juts into the two sounds like a bottom jawbone. “I can just tell you,” he says, “places where I used to walk in the marsh off of Point Peter Road and hunt here early in my career, now I could take a boat and fish in them.”

Lanier started working at the refuge when it was established in 1985 and has spent about 15 years there. He’s noticed some significant changes to the landscape.

“On Alligator River refuge we’re losing actual land base,” Lanier says. “We’re losing forest, especially on the areas that are adjacent to the sound. We’re seeing these areas be converted from forest to shrub.”

Supporter Spotlight

The signs of saltwater intrusion are subtle ones. Plant growth slows to a halt. There are fewer seeds, or the seeds that are dropped on the ground have a harder time germinating. High salt concentrations can draw water out of plants cells, stressing them out. The vegetation’s struggle to survive the salt, however, is not the only thing changing.

Saltwater intrusion eats away at the peninsula’s peat soil, lowering an elevation that is, on average, only two feet or less above sea level. Peat is a soil rich with organic plant litter that’s common in wet, acidic areas, and saltwater breaks it down faster. “When the soil decomposes, the elevation of the ground literally drops,” says Christine Pickens, coastal restoration and adaptation specialist of The Nature Conservancy’s N.C. chapter. “It’s called subsidence.”

“On top of that,” Pickens says, “the whole peninsula, well most of it, has been ditched and drained. These ditches allow the saltwater to work its way into the interior parts of the peninsula and chew away at that soil.”

Most of the eastern seaboard’s coastal plain has a similarly low elevation. What makes this region particularly prone to saltwater intrusion, Pickens says, is its extensive network of ditches and canals used for farming. What farmers use to drain excess water from their crop fields to the nearby sounds and creeks is precisely the conduit for saltwater to reach them.

This is farm country in the coastal plain of North Carolina between the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds. It’s some of the most productive agricultural land in the state and it’s surrounded by the second-largest estuary in the nation.

Driving down U.S. 264, through Hyde County, the first thing you’ll notice are ditches filled with water that run like a narrow moat parallel to the road. Then, you notice how most all the houses in the countryside sit three or four feet above the ground on gray concrete blocks. The crop rows, waiting to be planted after the winter, are saturated with water.

But, it’s the dead standing pine trees you see that give you the most pause. They’ve shed their needles, branches and dark brown bark. The trunks, pale as ghosts, loom in the marsh and green shrubbery like phantoms. These “ghost forests,” as they’re sometimes called, are all that remain of tress that can’t handle the encroaching saltwater.

It’s something the farmers are already dealing with every year, says Mac Gibbs, the former director for the Hyde County Center of the N.C. Cooperative Extension Service for 25 years. He’s worked locally as a farmer and commercial fisherman, too.

Gibbs was born and raised in Engelhard, a small fishing community in Hyde County, and lives on a property that his grandfather owned and farmed that backs up to the Pamlico Sound.

“We’re losing land all the time,” he says. “There are areas that used to be farmed in the late 1800s that are pure marsh now, and I’m talking about bulrush.”

As for the crops, Gibbs says today the saltwater only affects crops that are within a half mile of the creeks or, worst case, within a mile.

“They call it ‘saltwater intrusion,’ and I guess that’s the first sign of sea-level rise,” Gibbs says. “At first it starts affecting the yield, but then there’s sections of land, once it gets salt enough you can’t grow anything.”

Cotton puts up the best fight, he notes. And some farmers have tried introducing a more salt-tolerant soybean, though the yields aren’t up to par.

“Is it in their (the farmers) daily lives? Yes. Do they talk about it every day at the store? No,” Gibbs says.

“You can get the land back,” he adds, by pumping and diking or building tide gates to keep the saltwater off, but it can be expensive. Farmers are constantly comparing the tradeoff.

In the county next door though, the evidence is clear that the land is changing rapidly, says Dennis Stewart, the refuge’s wildlife biologist. Refuge scientists several years ago compared photos from the 1990s to 2012, he explained, and did some crude calculations. “Eight to 10 thousand acres had transitioned from forested wetlands to marsh,” he said.

These forested wetlands made up of bald cypress and pine trees, which are home to deer, bear, pileated woodpeckers and other critters, are gradually retreating and transforming into salt marsh. And while there’s always been a fringe of marsh between the sound and the forests on the refuge, Stewart says, in the past they were relatively narrow compared to today.

“When you look at it over successional time, it’s happening pretty fast,” Stewart says. “Within a three- to five-year period you can go from a forested wetland to a shrub-dominated wetland with a lot of tree snags (standing dead or dying tree). And then from a five- to 10-year period, you go from a shrub-dominate wetland to predominately marsh, still with some snags.”

The changes, he adds, will affect wildlife. “Those forest-dwelling species are not going to use the marsh so they’re going to have to move to other forested areas. And then the marsh species are going to love it because they’re going to get more marsh.”

The land managers are taking a more proactive approach, Lanier and Stewart both say, by starting to think about how they can adaptively manage the land to buy just a little more time for wildlife to move “up-gradient.”

“Yeah, it’s humbling to know things may not be here forever,” says Lanier. But, at least, he says, they’re trying to do something about it: “I get a lot of satisfaction out of the fact that we’re not just sitting back and watching things happen.”

“I think the hardest part about it,” he says, “is knowing we can only do as much as we can afford.”

Wednesday: Five researchers across several disciplines are joining forces to investigate the future risks of saltwater intrusion in this region and how its locals will ultimately play a role in conserving the land, or not.