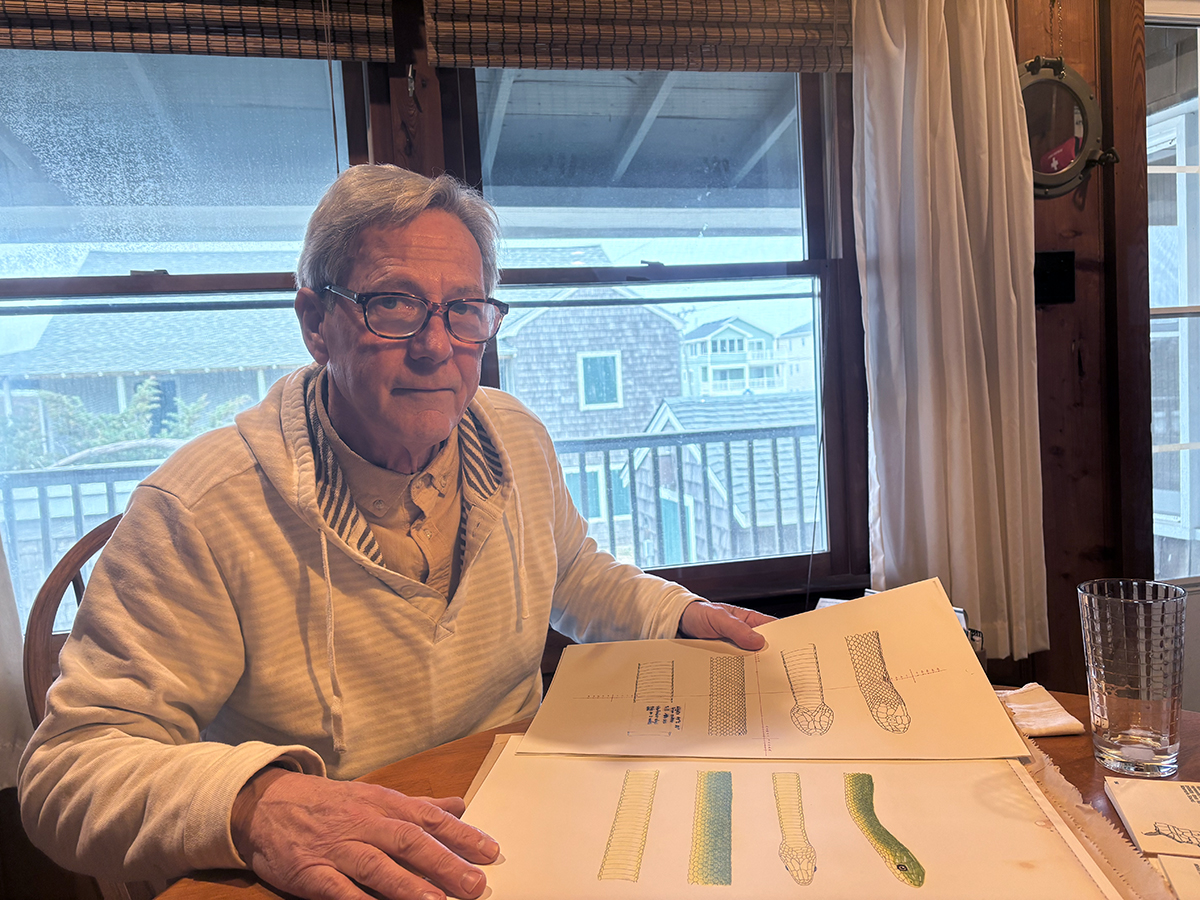

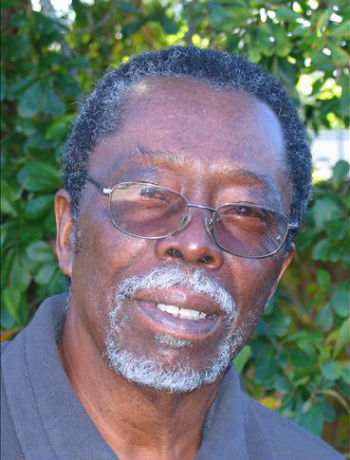

Don Ensley was the first board president of the environmental group, the N.C. Coastal Federation. He initially joined to help fight against proposed peat mining in Hyde County. Photo: staff |

GREENVILLE — Don Ensley was there at the beginning. When the N.C. Coastal Federation was formed in 1982, he was one of the founding members, the first president, in fact.

He hardly seems to be the typical leader of an organization working in environmental management. His background is in community activism, public health and academia, yet his philosophy of community engagement has become an integral reason for the success of the federation.

Supporter Spotlight

Growing up on a farm in Belhaven, a small town in Beaufort County, Ensley had no desire to inherit the family business. “That old concept of 40 acres and a mule,” is how he describes it, although he has modified his position. “I’ve learned some things about agriculture . . . Farming was black gold,” he adds.

He got off the farm, at least during the summers, when he stayed with an uncle who owned some property in New York City. “If that hadn’t happened I would still be in Belhaven,” he observes.

Looking back on that time and place, he has come to understand, although he wanted to leave as a young man, it has given him the strength to be who he is. “My growing up gave me a sense of place. It grounded me. It made me really identify with nature,” Ensley says.

His undergraduate studies took him to N.C. Central University in Durham, where he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in social biology and a minor in environmental health. He then started working in Chicago for one of the umbrella organizations of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Ensley was later accepted in Michigan State’s graduate program, but got drafted before he could begin.

He enrolled at Michigan State after his hitch two years later. “I got a discipline from the military that helped me to realize my goals,” he says. “I was more mature in my pursuit of what I wanted.”

Supporter Spotlight

He got his master’s degree in community health and a doctorate in higher education administration and served as an administrator in various programs — including a stint as associate administrator of the College of Osteopathic Medicine at Michigan State. “Can you imagine from a little boy from Belhaven who couldn’t even spell osteopathy, being asked to be the associate director?” he asks.

By the 1980s he was back in North Carolina with a master’s in public health from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a teaching position at East Carolina University, where today he is a professor emeritus in the university’s Division of Health Sciences.

He had just begun his career at ECU when a friend, Frank Adams, another founding member of the federation, told him about plans to strip mine peat in Hyde County and suggested he help the federation fight the proposal. “Well, I didn’t know what peat farming was even though I had been born and raised in eastern North Carolina,” Ensley said.

He learned that peat farming would strip the topsoil off hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland and change the ecology of the waters that were essential to the life of the communities along Pamlico Sound. As he learned about the effects the plan would have, his background in community activism came to the fore. “My interest is really about a community interest action model,” is his description.

Using that model, Ensley, the federation board and staff began talking to people in the small towns and villages and to farmers in the area. “We were able to get communities understanding what we were trying to convince the federal government not to engage in,” he says. “Through not just my leadership, but the board and other people in Raleigh we were able to convince the people in the fishing industry, crabbers how it was going to affect the estuaries.”

The battle to protect the farmland and estuaries took a number of years but was ultimately successful. The federation has continued its work in Hyde County and currently is working with local farmers to restore 2,750 acres of wetlands.

The original battle over the use of the land was, to Ensley, classic community organizing, going back to his first job after college. “We’re taught as a CAT (Community Activist Technician) you do not speak for the community. You assist,” he explains. “Your program may be the best program in the world, but if people have not been engaged in putting that proposal together and feel that they don’t feel they have ownership of it they’re not loyal to it.”

The community action model that the first battle the federation fought is a one that Ensley continues to champion. Although looking over the 30 plus years of the federation’s history, he sees a change in how the organization has come to be viewed.

“I think initially people saw us as a threatening entity,” he says. “But as we built strong relationships, not only in the community but in Raleigh, Chapel Hill and federal government, with nonprofits and others, we were able to convince people that we were not against progress. In fact we’re for progress . . . We weren’t just rhetorical. We weren’t just about stirring up people’s fears.”

As he looks to the future of the federation, Ensley sees both the hope and the concerns.

“Our communication with our leadership will have to continue to be to be encouraged, promoted,” he says. “We need to strengthen relationships with our communities to get their continued support. We’re going to have to continue to enhance our environmental programs and build strength with our younger generation. We’re going to have to be proactive in areas that have not necessarily been identified yet as environmental areas to be explored and looked at. We’re going to have to make sure that our pursuit of environmental changes are changes are that are going to benefit all citizens.”