MANTEO — Artifacts uncovered recently at a western Albemarle archaeological site suggest that settlers may have lived in the area around the time the Lost Colony disappeared.

In a report to donors, the First Colony Foundation reported that in only a few months, researchers have found more Elizabethan artifacts related to domestic activities than they have on Roanoke Island since the earliest English settlers vanished four centuries ago.

Supporter Spotlight

Foundation President Phil Evans called the findings an “extraordinary discovery.”

“At the site at western Albemarle, we have found evidence of the sorts of ceramics that would be most likely found in food preparation,” Evans wrote in an e-mail. “Where people cook, eat, and do so long enough to break some of their kitchen wares, we believe they may also be dwelling.”

Most of the artifacts from Fort Raleigh on Roanole Island are related to trade or a science center excavated in past decades — beads and copper aglets, as well as crucibles, bricks and tiles for a metallurgist’s furnace.

While the finds at the site on the western side of the Albemarle Sound may offer clues to where members of the Lost Colony ended up, they could be evidence of something else.

“We are encouraged to report that excavation at that site has revealed both Algonkian and English artifacts, including several noteworthy finds unlikely to have come from any source other than the Raleigh colonists,” Evans said.

Supporter Spotlight

He added, however, that “they could have come from the activities of any one of the colonial efforts between 1584 and 1590, or on an outside chance from some source presently undocumented.

“While what we have found is not large in numbers, we feel it is of high diagnostic value.”

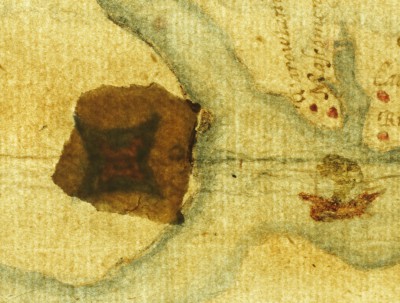

Called Site X, the dig is located where the Chowan and Roanoke Rivers meet in the western Albemarle Sound. It is in the area of an intriguing “breadcrumb” recently discovered on Raleigh Colonist John White’s map of the area, which he painted in the mid-1580s

The breadcrumb is a paper patch affixed over the area on the map.

When researchers at the British Museum undertook imaging and spectroscopic tests of the map a couple of years ago, they noted a four-pointed, star-shaped symbol with a cross in it, near the rivers, under the patch.

The symbol resembles a fort. But Evans has now disclosed, “We have no evidence of a fort. Whatever the site is, there is no evidence of a fort. A fort at this specific site does not seem likely. What is it? We don’t yet know.”

Evans said that John White fully expected at least some of the colonists would move farther inland at some point. But after White returned to England for supplies, then came back to America, a storm prevented him from exploring. He returned to Europe without a trace of his family and friends.

Evans said the foundation’s brief and limited survey of the surrounding area may also reveal an associated Algonkian village “almost adjacent to it.”

“There are high hopes that more good news will come in 2015,” he said. He said the foundation will make an official and more detailed announcement in the coming weeks.

He also said that archaeological excavation is only one early component of the study. In addition, the foundation must process and catalog artifacts, analyze samples and chart stratigraphy. “Specialists must extract conclusions from complex data and reconcile discoveries to their historical context.

“This is all very costly and important work, and it would not be possible without the loyal support of our generous donors.” He appealed to the general public to consider an investment in “this important next phase of our efforts to discover the discoverers.

“Our findings will write this missing chapter in American history,” he said concluded.

The First Colony Foundation is a non-profit organization made up solely of volunteers. It receives funds for research through donations and grants. Anyone wishing to help fund First Colony Foundation research may send a tax-deductible gift to 1501 Cole Mill Rd., Durham, 27705.