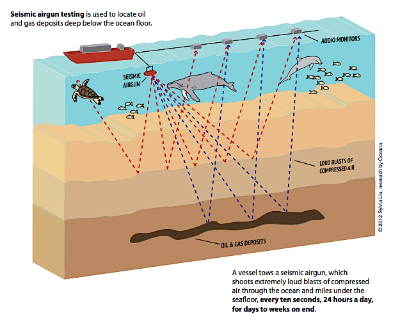

Seismic surveying will begin as early as next spring off the N.C. Coast. Seismic airgun testing is used to locate oil and gas deposits deep below the ocean floor. A vessel tows a seismic airgun, which shoots extremely loud blasts of compressed air through the ocean and miles under the seafloor, every 10 seconds, 24 hours a day, for days to weeks on end. Graphic: Oceana |

While the debate over drilling for oil and natural gas off the N.C. coast rages on, one thing appears certain: Next year, the first step in that process will begin, most likely in the spring.

Nine companies have applied for permits to use seismic air guns to look for likely deposits of oil and gas off the Eastern Seaboard, including North Carolina, according to David McGowan, executive director of the N.C. Petroleum Council. That work, he said, could involve multiple vessels in the same region at the same time, though he doesn’t expect tremendous overlap in a gigantic area that stretches down the East Coast from New England to the middle of Florida.

Supporter Spotlight

Still, when the nine companies are finished, some people fear that the ball will be set irrevocably in motion for drilling off North Carolina.

“If people in North Carolina don’t want to see drilling off their coast, and the impacts on the tourism and fishing industries, now is the time to stand up, often and loud, and make their feelings known,” said Claire Douglass, climate and energy campaign director for Oceana, an international ocean conservation group. “These oil and gas companies don’t spend this kind of money — $85,000 to blast one square mile — if they don’t fully expect to drill if they find something.”

The Obama Administration brought to the forefront again a debate that started in the 1980s when the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, or BOEM, announced in July that it would reopen the East Coast to offshore oil and gas exploration with sonic cannons. The announcement stirred deep concerns among local environmentalists, some beach towns and those involved in protecting and studying fish and marine mammals, including whales and dolphins.

Scientific and government estimates in the past pointed to a relatively small reserve of mainly natural gas off the East Coast. Reflecting that opinion, a report by a N.C. advisory panel on offshore energy a few years ago concluded that recoverable oil and gas deposits off the state’s coast might amount to as much as 690 million barrels of oil and 16.25 trillion cubic feet of gas, enough to supply 36 days of our country’s daily demands for oil and 246 days for natural gas. The federal government, in a more recent report, has estimated that the entire mid-Atlantic coast might contain 1.42 billion barrels of oil and 19.36 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, based on decade-old seismic surveys. Drilling proponents recently have been touting an estimate by ICF International, a Virginia-based management, technology and policy consulting firm, that this area could actually produce more than 5.8 billion barrels of oil and more than 29 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

As a comparison, the Gulf of Mexico — America’s largest known oil reserve — has almost 45 billion barrels of recoverable oil and Alaska has close to 38 billion barrels.

Supporter Spotlight

David McGowan |

McGowan noted that it’s been decades since any exploration took place in the Atlantic. Past efforts, he said, used equipment and methods that are antiquated compared to today’s standards. No one will know what’s really out there, he said, until someone goes out and looks.

“It’s by no means a certainty that no matter what is found, any drilling will be allowed,” he said. “That hasn’t been decided by the federal government yet. But given the energy situation in the country, we feel that we owe it to ourselves to use the best technology available and the best analysis available so that we have the best information possible to use in deciding whether to move forward.”

That’s what the nine companies intend to do. They will dispatch ships towing air guns about 50 to 60 miles out to sea. The guns will shoot loud blasts of compressed air through the water and miles into the seabed, which reflect back information about buried oil and gas deposits. While the federal government disputes that the guns are “100,000 times louder than a jet” – a commonly stated comparison – a fact sheet issued recently by William Y. Brown, chief environmental officer for BOEM, concedes that “measured comparably in decibels, an air gun is about as loud as one jet taking off.”

The noise and what it might do to animals within hearing distance is the biggest arguments against seismic testing.

William Y. Brown |

BOEM, Douglass said, allows the seismic boats to shoot the pulses of compressed air through the water every 10 seconds, sometimes for weeks or months on end.

To lessen the potential effect on whales and other animals, the agency’s environmental study of the East Coast testing includes areas that must be closed to testing at certain times and requires observers on the vessels to watch for right whales, dolphins and other marine mammals.

Those steps aren’t enough, Douglass said. “These sounds can travel tremendous distances and can still cause pain and damage and disrupt behavior at great distances,” she said. “And it does not really consider cumulative impacts, the repeated exposure. In the ocean, the mammals and fish are dependent upon sound, both to migrate and to communicate. These seismic guns pose tremendous problems.”

Although experts vary on the range of the danger, some say the pulses of sound can harm whales and other marine life with blasts of 230 to 250 decibels, so loud that they that can sometimes be detected up to 2,500 miles away.

Even if mammals are not within damage range, Douglass said, the sounds “are loud enough to kill small organisms like fish eggs and larvae.”

BOEM estimates that more than 138,000 sea creatures could be harmed, including nine of the world’s remaining 500 North Atlantic right whales. These whales give birth and breed off the coast of Florida, Georgia and the Carolinas before migrating north each year.

Brown’s fact sheet, however, states that, “To date, there has been no documented scientific evidence of noise from air guns used in geological and geophysical seismic activities adversely affecting marine animal populations.”

The technology, he said, “has been used for more than 30 years around the world. It is still used in U.S. waters off of the Gulf of Mexico with no known detrimental impact to marine animal populations or to commercial fishing.”

Areas along the East Coast that would be opened to seismic testing for oil and gas deposits off the Atlantic coast. Map: Bureau of Ocean Energy Management |

He also said it’s up for debate about the impacts on movement of marine species near the guns.

“We do not know what a whale, dolphin or turtle actually experiences when it hears an air gun,” he wrote. “Many marine mammal species but not the baleen whales, including North Atlantic right whales, have reduced sensitivity to sound signals that are in the same frequency range as airplanes and air gun arrays. Some whales appear to move away from surveys, indicating that they probably don’t like the noise, but bottlenose dolphins have often been observed swimming toward surveying vessels and ride [next to the] bow.”

He also disputed the figure of 138,000 injuries or deaths, or at least qualified it. “This statement misrepresents the facts,” he wrote. BOEM scientists studied what injuries marine mammals might sustain if nothing were done to lessen the effects of air guns. They then looked at ways to reduce the effects, such as such avoiding migration routes and stopping surveys if vessels get close enough to marine mammals to possibly injure their hearing.

“After a thorough, public process, the department selected a preferred alternative that included the most restrictive mitigation measures that would allow surveys to take place,” Brown wrote. “We expect survey operators to comply with our requirements and, if they do, seismic surveys should not cause any deaths or injuries to the hearing of marine mammal or sea turtles.”

Still, marine mammal experts, such as Keith Rittmaster, the natural science curator at the N.C. Maritime Museum in Beaufort, are worried about potential effects exploration might have on the animals.

Rittmaster has studied marine mammals extensively for more than two decades and has worked as a federally mandated observer on one of the sonic cannon vessels operating off Alaska.

“I can tell you it’s very loud,” he said. “I can tell you that while in my bunk on the ship, with ear plugs in and ear protectors over the ears, it was still loud.” And, he added, marine mammals depend on hearing underwater for almost all that they do, including navigation.

Keith Rittmaster |

Rittmaster said he doesn’t know of any case in which the sonic cannons have been proven directly responsible for the death of a marine mammal. But he added that any positive causal link would require quick access to a dead mammal, whether in the water or stranded on a beach, and that’s often a problem. There is clearly the potential for damage or destruction of tissue in the mammals and for, at the very least, changes in the mammals’ behavior, Rittmaster added.

“I saw, or at least think I saw – and it’s pretty well documented – such things as changes in travel direction, changes in diving patterns and even in the sounds they make in response to anthropogenic sounds,” Rittmaster said.

Rittmaster also conceded that there are known instances of some animals co-existing with sonic oil and gas exploration activities in the Gulf of Mexico.

Doug Nowacek, an associate professor of conservation technology at the Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort, has studied whale behavior in many areas, including the Gulf of Mexico, where seismic cannons have been used extensively for seabed mapping and oil and gas exploration for many years, and he’s worried, for a number of reasons.

Migratory marine mammals will be, at best, severely stressed, and at worst, will simply leave, he said. Other, more local whales, like pilot whales, might want to leave but might not do so because they really don’t know where else to go.

“This is their home,” he said. “It’s like if it was happening in your neighborhood. Where are you going to go? It’s all you know.”

North American right whales, a federally recognized endangered species, migrate along the East Coast. Opponents of seismic survey are worried they will be adversely harmed by the airgun blasts. Photo: Sea to Shore Alliance |

Nowacek noted that the companies usually do pay attention to the observers on the vessels. But, he said, the blasts are basically continuous, day and night, and during inclement weather. It’s not at all clear, he said, whether observers would even see the whales and other marine mammals in the dark or under inclement weather conditions. And there’s also no way to know which direction the animals might go if they dive.

While it’s unlikely that that a whale or other marine mammal will get close enough to the blasts to have its eardrums blown out, Nowacek said, the cumulative effects are important. It’s like a human being in an area where a jackhammer is being used, constantly, for months on end. Stress increases dramatically, he said, and we know from studies on rats and humans that there are almost sure to be negative impacts on all kinds of things, including feeding and mating. And there’s no doubt that the sounds mask the animals own sounds, making it difficult if not impossible for them to hear each other. Essentially, in a world where sound is the key to communication, the seismic blasts can render an animal “blind.”

It’s important to note, Nowacek said, that the seismic blasts won’t be just a one-time thing. If the initial effort finds areas that are promising in terms of oil and gas production, multiple companies will come back to do more and more powerful blasts in order to fine-tune where to drill. And even after drilling, there will be periodic seismic activity to determine how much has been removed and what might remain. In other words, Nowacek said, once this whole thing starts, it is likely to become the new normal in at least some areas.

Interestingly, he said, humans might also have to get used to it: surfers and swimmers, he said, can hear the pulses underwater — the sounds travel that far.

Claire Douglass |

Oceana’s chief goal, Douglass said, is to try to persuade the federal government not to include the Atlantic Coast in the five-year energy plan that will begin in 2017 and end in 2022.

“It’s just not worth the risk,” she said, “and not just because of the impact on marine life. Do people on North Carolina’s Outer Banks want to see tar balls washing up? Does anyone want another Deepwater Horizon?

“We recently started a campaign in Myrtle Beach,” she added. “These areas are so dependent upon clean water for tourism and for fishing. People might think that now, 2014, is too far in advance to fight, but it isn’t. It’s just around the corner.”

Nowacek said the whole testing-and-drilling issue poses basic questions that we need to ponder and answer.

“If we don’t want this [seismic tests and offshore drilling], what then?” he asked. “We can’t just continually say, ‘Go drill somewhere else.’ At some point, we either have to accept this or get serious about alternative energy.”

McGowan thinks there’s relatively little risk and great potential for the state in oil and gas exploration and production.

“I grew up in Wilmington and still have family there and along the northeastern part of the state’s coast,” he said. “I’m convinced this [seismic testing] is safe, and more importantly, so does BOEM. This has been done for many years and in many areas, and with a good track record, and the protective measures are pretty robust.”

Seismic Survey to Study Formation of Atlantic OceanBy Brad RichThose looking for oil and gas won’t be the only ones bombarding the ocean floor with sound waves. Scientist may use air guns off Cape Hatteras as early as next week to study the creation of the Atlantic Ocean. As part of a collaborative research project with Columbia University, the National Science Foundation plans to send a ship from Monday to Oct. 22 towing 18-36 air guns to investigate how the continental crust stretched and separated during the opening of the Atlantic Ocean more than 100 million years ago. The project site is between 10 to 262 miles off Cape Hatteras. Donna Shillington, an associate research professor at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, said the work is important and the results could change what we know and think about the formation of the Atlantic Ocean and the breakup of Pangea, the “supercontinent” that included what is now North America, Eurasia, South America, Antarctica, Africa and India. The supercontinent, geologists believed, formed around 300 million years ago in the late Paleozoic Era and began to break up 100 million years later, during the early Mesozoic. It was the last of a number of supercontinents that existed, the result of constantly moving, colliding and separating plates of the earth.

“This project is designed to help us understand how these continents broke apart to form the ocean,” Shillington said. “It happened all the time. But we don’t really understand why. We do know that it’s very hard for 100-mile thick piles of rock to break apart.” There are, she said, a number of possible reasons for the breakup, including magma that heated up and weakened the boundaries. The rocks under the sea off North Carolina and Virginia, as well as some of the formations on land, are thought by scientists to hold a lot of clues about those ancient areas of weakness and separation. “This is one of the fundamental processes that made the earth what we know today,” Shillington said. “It will increase our knowledge of that process, and it will also give us new information about some more recent things, such as submarine landslides that have occurred all along the East Coast.” The study isn’t related to oil and natural gas exploration or development. But the scientific survey is similar in methodology to the testing for oil and gas. It stirred some of the same fears about effects on marine mammals and on fish, especially since the fall fishing season is nearly underway in the state. The latter concern was important, according to Michelle Walker, spokesperson for N.C. Division of Coastal Management. “The time they want to do this is during fall fishing and there are a lot of productive fishing areas where the survey will be,” she said when the proposal first came to light. The division is responsible for determining whether projects like this one are consistent with the state’s coastal-management law. If it finds a proposal inconsistent, the federal government couldn’t issue the necessary permits. The scientific study was consistent with state laws, the division notified the National Science Foundation in a letter Monday, as long as the scientists followed the same mitigation measures – placing observers on the ship and using acoustic monitors – as are expected to be required when private companies begin testing for oil and gas surveys. If such steps aren’t taken, the state would object to the project, the letter says. Foundation officials late Monday acknowledged receipt of the letter, but as of Wednesday afternoon had not responded officially. Maria Zacharias, a foundation spokeswoman, said late Monday afternoon that the state’s letter was “under review” and the goal was to reply in a timely fashion. She said information on the foundation’s response to the state should be forthcoming in the next few days on its website. The scientific work also has raised concerns among the state’s commercial fishermen. Jerry Schill heads the New Bern-based N.C. Fisheries Association, a trade and lobbying group for some commercial watermen. He had submitted a letter to the state about the project, urging it to object. “Due to all the uncertainty about the project and how it would affect many aspects of our coastal life including but not limited to commercial and recreational fishing, the North Carolina Fisheries Association urges you to reject the NSF’s consistency determination for this project,” Schill wrote. Town commissioners in Nags Head also formally opposed the project’s application, and other local governments have expressed concerns. There are also concerns about the impacts the seismic blasts will have on marine mammals, especially whales. Doug Nowacek, an associate professor of conservation technology at the Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort, has studied whale behavior in the Gulf of Mexico, where seismic cannons have been used extensively for seabed mapping and oil and gas exploration for many years. He said he’s not overly concerned about the science project, since it’s of relatively short duration and is a “one-time thing.” Nevertheless, he said, there are likely to be some at least temporary movements of fish and marine mammals away from the area. That could be a problem off Hatteras, where there are high concentrations of marine mammals, he said, and in Onslow Bay, off Carteret and Onslow counties, at a time that is important to both fish and fishermen. Likewise, Claire Douglass, of the Washington, D.C.-based environmental organization Oceana, is concerned, but not alarmed. Oceana, she said, believes this project is small enough in scope, and the duration is short enough, that few significant impacts, if any, are likely. “It doesn’t mean it’s good for marine life, but we’re not really objecting to it,” she said. According NSF’s environmental impact statement for the project, the potential impacts of the seismic survey would primarily be increased underwater noise, which could result in avoidance behavior by marine mammals, sea turtles, seabirds and fish that temporary leave or stay away from an area due to the noise. “An integral part of the planned survey is a monitoring and mitigation program designed to minimize potential impacts of the proposed activities on marine animals present during the proposed research and to document as much as possible the nature and extent of any effects,” the foundation says in the study. |