ORIENTAL – Allen Propst, a Pamlico County Realtor and occasional developer, didn’t just roll out of bed one morning and decide swampy forestland was worth protecting.

In fact, if you get to know him a bit, you might conclude that Propst had been rehearsing most of life for his role in the ongoing fight to stop possible illegal ditching and draining of wetlands in the 4,700-acre forested “Atlas Tract” tract near his home in Oriental.

Supporter Spotlight

It’s a role that earlier this month won him a Pelican Award from the N.C. Coastal Federation, and while it might seem an odd one for a Realtor who grew up in Concord, near Charlotte, it really isn’t.

Propst, after all, fell in love with rural, watery and beautiful Pamlico more than four decades ago, in 1973, when he visited as a junior studying for a wildlife biology degree at N.C. State University. “I loved hunting and fishing, and it was just a perfect place for that,” he said recently. “I loved the small town atmosphere, the beauty, the wildlife.”

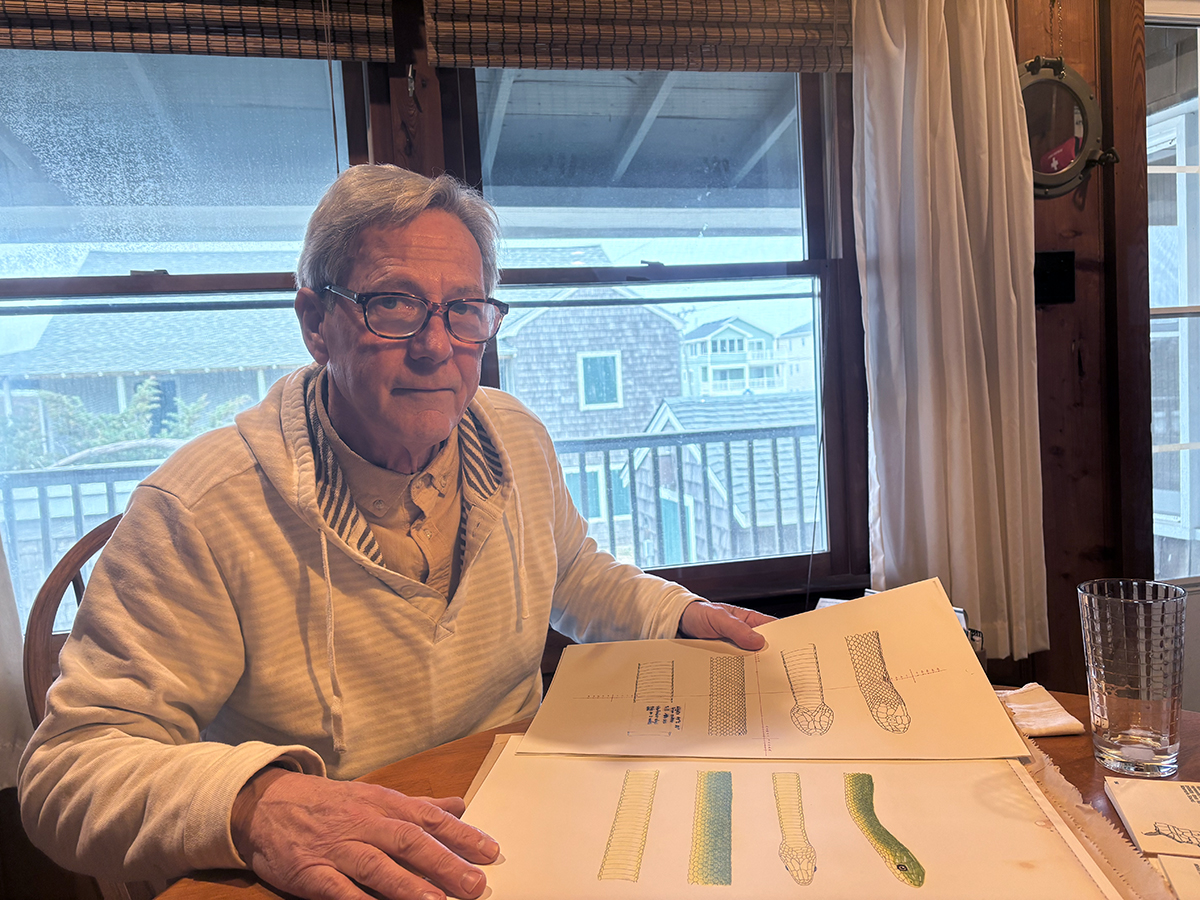

Allen Propst, center, accepts his award from Todd Miller and Lauren Hermley. Photo: Sam Bland |

He knew he eventually would make it his home, and four years later, he was back as a full-time resident. Ten years after that, he opened Mariner Realty in Oriental. He calls his role in the ongoing Atlas Tract saga a “perfect storm.”

He graduated N.C. State University in 1974 with a wildlife biology degree. There wasn’t much you could do with such a degree except work for the state or federal governments, but there was a recession going on and a federal and state hiring freeze. Some kids went back to college for advances degrees; others like Propst drifted from one unsatisfying job to another.

One day while sitting around trying to decide what to do with the rest of his life, Propst decided to go duck hunting in Canada for a while. “So I packed up my two dogs and pretty much everything I owned in a Chevy Blazer and took off,” he remembered.

Supporter Spotlight

He ended up in northern Manitoba, which was pretty remote. After several weeks of killing countless ducks – “You can only eat so many and you couldn’t even give ‘em away there were so many,” he said – Propst visited a Ducks Unlimited office to look for work.

The folks there referred him to their office in Saskatchewan, which was farther west and even more remote. Propst called the manager and got a job. He stayed until 1977, getting a civil engineering degree at a technical college along the way. Moving back to the United States, Propst settled in Pamlico County, near his good friend and fellow State graduate Buck Jones, who was farming near what would later become known as the Atlas Tract. Propst brought with him a great appreciation and love for wetlands, not to mention extensive knowledge of what they are and how valuable they were to Pamlico County and similar places.

“When I was working with Ducks Unlimited, I spent a lot of two summers in the wetlands,” he remembered. “They were looking at how to improve duck habitat, and examined what happened to wetlands when you ditched or drained them.”

He and his wife, Angie, opened a real estate office in 1987.

They did well, to say the least. He became a consistent “million-dollar producer,” a president of the Pamlico County Board of Realtors and president of the Oriental Rotary Club. He put down roots. Life was good; he still loved hunting and fishing, though he admits he eventually became more of a golfer than an outdoorsman. But he didn’t forget what he knew about wetlands.

And at one point, about three years ago, he was hired, by its then-owner, Copper Station, to try to sell the Atlas Tract as hunting tracts.

“I had the key to the property and a four-wheeler, and I spent about a week learning the lay of the land, trying to find where all the deer and turkeys were so I could show the potential buyers where the good stuff was,” he said. “That’s how I knew, when Buck called, that this whole tract or the vast majority of it anyway, was wetlands, and that draining and clearing it to convert it to agriculture was going to be illegal.”

The 4,658-acre tract it was later sold, through a different real-estate agent, to Spring Creek Farms LLC, which is registered in Illinois, according to Pamlico County tax records. About 250 acres on the south side of State Road 1324 had been cleared, a fact acknowledged at the time by Abel Harmon of Hydeland Construction & Consulting in Swanquarter, which was working on the project. Farming, Harmon said last September, “could begin any time” after the land clearing was completed.

Propst started sounding alarm bells on social media, online news outlets and letters to those in a position to do something about what appeared to be the first massive forest-to-farmland conversion effort along the N.C. coast in decades.

One who heard the alarms was Todd Miller, the federation’s executive director. He contacted federal and state regulators about the project in early August, inquiring about the history of ditching and contesting the regulators’ assessment that wetlands hadn’t been illegally drained. Propst, meanwhile, urged resident to write and call their county commissioners and attend commission meetings.

Hundreds did. They wrote those letters and emails and attended those meetings. The commissioners fired off official letters to the Army Corps of Engineer, demanding further investigation. Finally, the matter landed in the hands of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which is reportedly still considering exactly what kind of “enforcement action” should be taken. Not much has happened on the land since then.

Propst said at the time he had never seen an issue so galvanize residents of rural Pamlico County; it was bigger than the tussle a few years ago over a Walmart.

“Everyone I talked to, or just about everyone, is against this,” he said last fall in an article for Coastal Review Online, which broke what became a big story. “On other big issues, things are usually about half and half, but not this. People are very concerned and upset. There is a lot of land where this could happen, not just this tract, and the impacts would be devastating on our water quality, our fishing, our environment, just from this one conversion, if it’s allowed.”

Clear-cutting small tracts, if done periodically, can be beneficial to wildlife by creating an edge-effect of new forage without dramatically destroying entire ecosystems, Propst said. But converting wetland forest to farmland would permanently and forever destroy vital habitat not only for the hundreds of deer, bear and wild turkey but for the thousands of birds and smaller mammals that will be permanently displaced.

The tract, he said, as well as other large wetland forest tracts in eastern North Carolina, serves as a vital winter habitat for migratory songbirds for several months during the winter. And there are other vital functions, not least among them the fact that the tract serves as a sponge, soaking up rain that otherwise would wash pollutants – bacteria, pesticides, herbicides and other toxins – into the creeks and eventually into Pamlico Sound, North Carolina’s vast and productive inland sea.

Conversion of the tract to farmland, as a farming outfit surely would do, would hasten and worsen all of those, Propst believes.

“The county is concerned that clearing, drainage and conversion of this tract from forest to agricultural land will increase the risk of flooding in low lying areas, destroy wildlife habitat and degrade coastal water quality and fisheries,” the commissioners said in their letter.

Beyond that, Propst and the commissioners said, there’s a basic fairness factor. It’s important, the commissioners wrote, that all landowners and farmers engaged in forestry and agricultural practices be held to the same standards.

Asked if he’s glad he sounded the alarm, Propst didn’t hesitate. “I feel great about what I did,” he said. “I’ve gotten tremendous support from the environmental community and from the people of Pamlico County. But the proof will be in the outcome. Will it help stop wetlands conversions?”

And, while Realtors and even small-scale developers, Propst knows, often suffer a reputation not altogether different from used cars salesmen – anything for a buck – he sees no contradiction between the way he makes his living and the way he has fought for the flora and fauna living along the coast. It’s all, he said, about “highest and best use,” one of the most important but sometimes least understood concepts in real estate.

Some land, simply put, is most valuable and important in its natural state, doing the things land in its natural state does: protecting water quality and habitat and providing a place for hunting and fishing.

“I’ve got nothing against farming,” Propst said. “Buck Jones, my best friend, is a farmer. But there needs to be a balance, and that’s what I have tried to do: make sure we keep a balance.”