Reprinted from the Island Free Press

Blanche Howard Jolliff at her 93rd birthday party. Photo: Ocracoke Current |

OCRACOKE — Blanche Howard Jolliff is 94 years old and she recalls many things from her childhood on Ocracoke Island: Riding in a horse-drawn cart across the beach to see a shipwreck; dining on sea turtle hash; going out in her daddy’s fishing boat that he named for her; and eating her mother’s delicious sweet potato pie.

Supporter Spotlight

Blanche is the daughter of Elizabeth Ballance Howard and Stacy Howard, both native Ocracokers. Born in 1919, she was delivered at home by Ocracoke’s renowned midwife, Charlotte “Miss Lot” O’Neal. She grew up on Ocracoke, living in her parents’ house on Howard Street until the early 1950s, when she met a young man who was looking into building a highway on the island.

The newlyweds moved to the mainland, but Jolliff came back about once a month to see her family. After her husband’s death in 1994, she moved back for good, and she lives once more in the home on Howard Street where she grew up.

Blanche’s father, Stacy Howard, was an island fisherman. He came from an old island family that’s been here since the early 1700s. His father, P.C. Howard, had a home on what is now known as Howard Street, across from his father’s home. P.C. raised Stacy and the rest of his family in the traditions of the Southern Methodist Church, also on Howard Street. In the early 1900s, Stacy had a house built near his father’s and grandfather’s homes.

Jolliff’s mother, Elizabeth Ballance Howard, was the daughter of Aaron and Lois Anne Williams Ballance, whose “old home place” was Down Point, nearer to the lighthouse. The Ballances, according to Jolliff, were originally from Hatteras. Elizabeth and Stacy married in the early 1900s.

Supporter SpotlightElizabeth Howard made the best sweet potato pies on Ocracoke. |

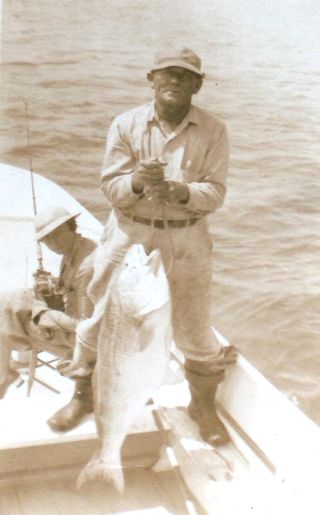

Stacy Howard came from an old line of island fishermen. Photo: Ocracoke Preservation Society |

Stacy Howard often talked about shipwrecks on the islands. He told about a time in 1899, when he was about 5 years old, when the ship, the Pioneer, came into the inlet with cargo and wrecked on the beach. Clothes, shoes, fruits and vegetables were everywhere, and people would find one shoe, then search for its match. Stacy’s father, P.C., came home with a big cheese.

Jolliff recalls hearing about another occasion when a ship came ashore near Nags Head, and top hats were all over the beaches. Someone auctioned them off, and island boys bought them and wore them.

Things got tough on Ocracoke that after the Civil War, Jolliff said. Railroads replaced schooners as the primary way of moving goods. The jobs that those schooners had provided jobs for many Ocracoke became scarce, she said. Like many Ocracokers, Jolliff’s father often went north to work on dredges in Pennsylvania and Delaware. When the rivers froze, he and the others would come home. Back at Ocracoke for the winter, Stacy took out hunting parties in his boat, especially before the Depression in the 1930s.

Looking back over the years, Jolliff describes what life was like back then for her and her three sisters — Leila, Etta, and Lois — as they were growing up. “Papa had a big garden out back, and Momma kept chickens,” she said. “Everybody did back then. They hatched them out at first, and later ordered them in the mail, and they came in boxes. My mother took care of them, feeding them twice a day. They ran around free and sometimes they’d get into trouble–scratch up someone’s garden.”

There were all kinds–dominiques and red ones and buff ones — raised for the eggs and meat.

“Sometimes when we were young Etta and I would chase them around and get them squawking,” Jolliff remembered. “It was the best fun, but then we’d get in trouble.”

She also remembers the ponies that wandered around freely in the village. “Sometimes folks would ride them to the store, tying them outside while they shopped,” she said.

As for cows, she says there were four places where they were raised and where milk was sold. Blanche’s family went out to a place on the Back Road to buy their milk.

When Jolliff was very young, her mother made all their bread. By the time she turned, Will Willis was bringing bread from the mainland on the daily mail boat. Her mother continued making rolls—hot and very fluffy—nearly every day. Her family ate fish, clams, turtle, chicken and vegetables. Without refrigeration, fresh meat was a rarity. Everyone had a vegetable garden, with cabbage, string beans, collards and sweet potatoes.

“My mother made the best sweet potato pie,” Jolliff said.

She also made pineapple cakes, and Blanche’s sister Leila loved to make chocolate cakes.

One of Jolliff’s favorite foods was turtle. She recalls that before they were protected by federal law, fishermen caught sea turtles in their nets and brought them back to the fish house at the Community Store. They would quarter them and give each quarter to a family.

The turtle was parboiled for “a good while” to make it tender, Jolliff said. “Then you cut the meat off the bone. You cooked it with onion, potatoes, and a little bit of salt pork,” she said. “We called it turtle hash, and you had to have baked cornbread with it. You never tasted anything so good.”

The foods they did not grow came mostly from Mace Fulcher’s Community Store, but there were other stores on the island too. Jolliff remembers that Uncle Ike had one at the old post office building, and Albert Styron had one Down Point. Clarence Scarborough ran a store at what is now the beauty parlor, and Walter O’Neal had a store and dock on The Creek. Travis Williams ran a store near what is now the Harborside, and James and Charlie Williams had one across from Della Gaskill’s house.

The house on Howard Street where Blanche grew up and lives still. Photo: Pat Garber |

Back then there were two or three fish houses. There was no refrigeration in those early days, but big blocks of ice, used for keeping food cold, could be bought at the fish houses. When Ocracoke got electricity in 1938, the Ice Plant opened down on the docks, but it didn’t last long, just a few years at most, as Jolliff recalled.

Most people back then heated with fireplaces, and Jolliff remembers a visit to her father’s first cousin’s house when, at age 8 or 9, she “froze on one side and burnt up on the other.” Jolliff’s family had a coal stove and chromium stove which burned wood in the early years, pellets later on. Her mother ironed clothes with a flat iron, which was heated on the wood stove.

While growing up, Jolliff played hopscotch with neighboring children, and they played in make-believe houses and kitchens, using broken dishes and making pretend desserts with red sand. She recalls pretending a piece of cedar was chicken. They also filled the tops of coffee cans with mud, let them dry, and put them together to make make-believe layer cakes. They played with dolls, which they usually got for Christmas, often bought at Fulcher’s store but sometimes ordered from Montgomery Ward, Sears & Roebuck, Charles Williams and, later, J.C. Penney.

In Jolliff’s early years almost all transportation was by water. She remembered that “when I was young there were only two or three vehicles on the island. There were two freight boats, which went to Little Washington or Morehead. There were two mail boats, and one went one day, one the next. The first one came out of Beaufort, and after that from Atlantic.”

Jolliff’s uncle had a horse and cart, and he’d give the girls rides. “Once, when I was about 5, I went out across the beach with my uncle and aunt to see where the ship, the Victoria S, had fetched up on a shoal,” she said. “The ship was still in the water, loaded with lumber, but it could not get off the shoal.” Blanche thinks that they eventually dynamited it to get rid of it.

That shipwreck Jolliff said, led to the first road and vehicle wreck on Ocracoke. “The owner of the lumber had it unloaded and stacked on the beach,” she said. “He wanted to get the lumber shipped to the mainland. Two of the island men got the idea that they would each buy a flatbed truck and haul the lumber from the beach to the docks where it could be shipped.

Ocracoke Islanders salvage the wreck of the three-masted schooner Nomis, which ran aground on the island in 1935. Photo: Ocracoke Preservation Society |

“But there wasn’t a road the whole way, so they got permission to cut through the oak and myrtle in front of Blanche’s house and make one. It wasn’t very wide, and there was deep sand. In order to get through the sand they had to gun their engines and try to plow through it fast. One day the two trucks met head-on at the sandy stretch, and this was the first wreck on the island.”

No one, fortunately, was hurt.

As more cars were brought to the island, people would drive down the lane in front of her house, now Howard Street. There was a big oak there, she recalls, and sometimes the cars would run into the tree. Because it was still sandy, on more than one occasion, she remembered people knocking on the door and wanting to borrow a shovel to dig out their cars.

As a teenager, Jolliff would sometimes go to Washington, N.C., on the freight boat. She was friends with Capt. David William’s daughter, Virginia, and they would go together. Virginia had a friend who lived there, and she would meet them at the dock. Then they would spend the night at her house.

During World War II, there was a naval base at Ocracoke, and “lots of men were stationed here doing work so that the boats could get in and out of the harbor,” Jolliff said.

“The men brought their wives, and people rented them rooms,” she explained. “I wasn’t really afraid during the war, but it was sad—they found so many bodies, and the torpedoes sounded awful, so loud…The sky would turn a deep pink—it was that close—and then we heard them afterwards. We had black-out curtains so that the lights wouldn’t be seen on the beach.”

Many of Jolliff’s cousins and friends went off to fight in World War II. Thurston Gaskill’s youngest brother, Jim Baum Gaskill, was on a freighter that was torpedoed within sight of Ocracoke. Most of the men died, including Jim Baum, she recalled.

When she was 22 years old, Jolliff took a job working at the Post Office. One day an interesting man came in to get his mail. Guthrie Jolliff had come to Ocracoke with an engineer and a planner to look into building a new road—N.C. 12—down the island. He continued going to the Post Office, and before long he and Blanche were seeing a lot of each other.

They got married and moved to Hertford County, and later to Belvidere. They tried to come back once a month, so that Jolliff could see her family. In 1994 Guthrie died of a heart attack. Blanche made plans to move back to her family home, but she “had to wait two years after a hurricane shook it up and it had to be repaired.”

Looking back, Jolliff remembers that “Ocracoke was a good place to live.”

“Parents didn’t have to worry about their children then. There have been a lot of changes, but it’s nice to recall it. Childhood was a happy time.”