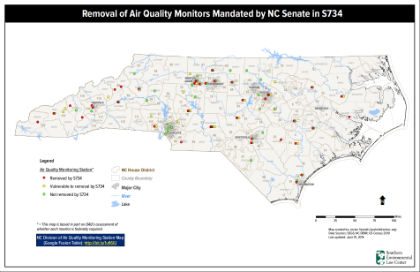

The red dots represent the 77 state air quality monitors that would be removed if the new Senate bill passes. Graphic: Southern Environmental Law Center |

RALEIGH – The short session in the N.C. General Assembly takes another twist. The Senate rewrote omnibus legislation yesterday — stopping just short of passing — that includes several controversial environmental provisions previously seen and rejected by the House. The new bill drew immediate criticism.

The new bill, the 62-page Regulatory Reform Act of 2014, was added with little notice to the Senate Rules Committee agenda yesterday morning. After approval by the committee, the bill was sent to the full Senate. Instead of voting on the new bill, however, the Senate took up a different regulatory reform bill to send to the rules committee for review this morning as a likely alternative should the new bill not pass.

Supporter Spotlight

Among the new omnibus bill are provisions that would drastically weaken state protection of certain wetlands, make it harder for people to challenge coastal development permits and eliminate an estimated 77 of the state’s 133 air quality monitors.

“It’s end of session shenanigans,” said the state director of N.C. Sierra Club, Molly Diggins, of the Senate’s moves. “The House had already removed these provisions. There’s been a lot of bad stuff this year, but these are the most egregious of the group.”

House members were quick to signal their consternation with the Senate’s move. The House had taken a similar regulatory omnibus and divided it into three bills. One of them, the Amend Environmental Laws 2014, passed 97-13 in the House but has sat untouched in the Senate Clerk’s Office since.

Rep. Chuck McGrady |

Rep. Chuck McGrady, R-Henderson, who worked on the House version, said he does not think the House will sign on to the new bill.

“We passed an environmental amends bill, and the Senate is holding that in the Clerk’s Office,” McGrady said. “If they want to add back environmental provisions of whatever sort, they ought to vote not to concur and we can have a conference on that bill. I oppose their now adding back the environmental provisions that we’ve already considered and struck.”

Supporter Spotlight

McGrady said he remains against the plan to eliminate air quality monitors that are not required to enforce federal rules. DENR announced its opposition to the elimination of the monitors earlier this month.

Earlier this year the Department of Environment and Natural Resources identified several monitors in the coastal region that would be eliminated under the plan, including mercury monitors at Lake Waccamaw and air toxins monitors in Martin, Beaufort and New Hanover Counties.

Diggins said there’s been little reason given for the move, aside from the description of streamlining the fleet of monitors to only what’s needed under federal rules.

“The simple reason is that if you don’t know you’re polluting, you don’t have to do anything about it,” Diggins said. But in the long run, she said, that could come back to hurt industries. “Having the monitors lets you get ahead of the curve.”

Molly Diggins |

Cassie Gavin |

The monitors have helped the state make great strides in cleaning up its air, she said. “This is a recipe for going backwards.”

Isolated Wetlands

The Senate bill also loosens the standards in place to protect isolated wetlands, which are small tracts of wetlands that aren’t directly connected to a waterway. The state currently requires a permit for any development activity in isolated wetlands that is larger than a third of an acre east of Interstate 95 and a tenth of an acre west of the highway. The new provision would raise the threshold to one acre anywhere in the state before a developer would be required to obtain a permit.

That high of a threshold would probably cover most of the state’s isolated wetlands, according to Cassie Gavin, the director of governmental relations for the N.C. Sierra Club. The bill also doesn’t take into account the differences in eastern and western North Carolina.

“It leaves in place a system of protection,” Gavin said, “but the threshold takes it away.”

CAMA Permits

The bill also alters a long-standing rule on challenges to permits issued under the Coastal Area Management Act. Currently, if someone challenges such a permit, the permit is automatically suspended until a decision is reached at the hearing. Under the new provision, the permit would remain in effect and work would continue as usual while the challenge is under review.

The review process entails convincing the chairman of the Coastal Resources Commission that the permit challenge has merit. The case would then be heard by an administrative law judge. The entire commission would have to approve the challenge under the bill.