They’re often bowl-like bodies, depressions in the landscape usually smaller than an acre that, on the surface, can easily be overlooked.

They’re called “isolated wetlands,” because they’re not directly connected to any body of water, and to a large degree, they remain a mystery.

Supporter Spotlight

John Dorney |

These small, freshwater wetlands are thought to pepper North Carolina’s coastal plain by the thousands, though no one knows how many isolated wetlands are in the state.

What environmental experts who’ve studied these pockets of land say is certain is that isolated wetlands are an invaluable part of the ecosystem and must remain protected.

Two competing bills in the N.C. General Assembly, however, would virtually eliminate any state protection of isolated wetlands along the coast and could weaken them elsewhere.

These often are perched above groundwater, giving some the appearance of nothing more than a mud puddle, a term at which experts bristle because it’s not only an inaccurate depiction, it downplays their hydrological and ecological value.

“In terms of water quality they don’t do very much except in their absence,” said John Dorney, the former head of the Program Development Unit in the N.C. Division of Water Resources who spent much of his career studying wetlands in the state. “If they get wiped out that will cause a problem. With few exceptions they’re connected to downstream. These things are intimately connected to the groundwater.”

Supporter Spotlight

These wetlands ability to recharge groundwater is one of their valuable functions, Dorney explained. “Most of the people in the coastal plain drink groundwater,” he said. “If you fill these isolated wetlands in with parking lots you’re not going to recharge the groundwater. This is particularly important now as it relates to climate change and streams drying out.”

The state’s isolated wetlands are regulated under state N.C. Environmental Management Commission rules that require an individual or general permit.

The EMC in 1996 established the current rules following two U.S. Supreme Court decisions more than a decade ago that effectively removed isolated wetlands from the Army Corps of Engineers permit requirements.

Over the years the state’s rules have been challenged by developers, but ultimately upheld by the N.C. Court of Appeals in 2002. The legislature is now considering changing the regulations, the results of which could all but diminish current isolated wetlands protections.

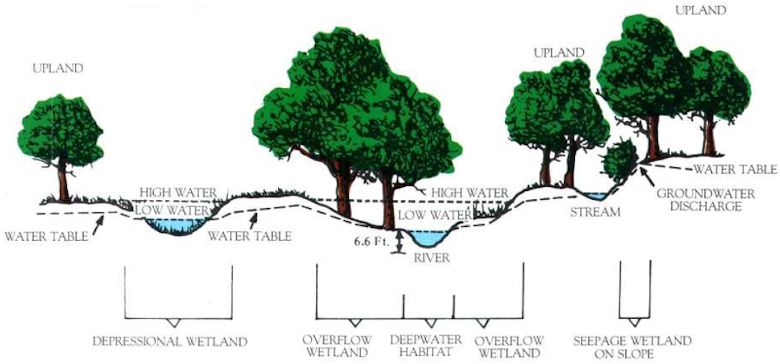

The depression on the left would be considered an “isolated wetland” because it isn’t directly connected to the river in the center yet sits on a low spot on the water table. Illustration: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Since the state developed the isolated wetlands program the number of permit requests pertaining to these wetlands has steadily risen, according to a 2012 report.

The report, published by the N.C. Coastal Resources Law, Planning and Policy Center, examined records from the state Department of Environment and Natural Resources and found that about four percent of permits issued from October 2001 through 2011 pertained to isolated wetlands.

During that time frame, the state issued 259 permits to “alter approximately 71 total acres of isolated wetlands statewide.”

“Of the 71 acres statewide, approximately 30 acres were located in the coastal counties,” according to the report. “The authorized isolated impacts in the coastal counties ranged from a low 0.0007 acres to a high of 1.58 acres.”

Since 2007, DENR has issued 15 isolated wetlands permits totaling about 5.47 acres of permitted fill in the state’s coastal counties.

Two bills in the legislature could weaken state protections of isolated wetlands, particularly on the coast. Currently, the rules require a permit for any project larger than a third of an acre east of Interstate 95 and a tenth of an acre elsewhere in the state.

The state Senate, in the broad environmental rules bill it passed a couple of weeks ago, would increase the permitting threshold to an acre anywhere in the state. The N.C. House’s version, passed last week, would triple the threshold in the Piedmont and mountain to a third of an acre but, like the Senate, exempt all projects under an acre along the coast.

Such proposals would exempt every coastal project permitted since 2007.

Source: Wetlands Professional Services |

Wetlands Professional Services |

Isolated wetlands come in many forms, from top:a palmetto forest on poorly drained soils, a small depression by the side of a road and a bottomland hardwood forest. Source of bottom photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

“The proposal of the legislature to increase the threshold to one acre makes the rules meaningless,” Dorney said. “Just get rid of the rules period. Why play that game?”

Dorney, a senior environmental scientist for a private company, took part in a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency-funded study a few years ago assessing isolated wetlands in an eight-county area of southeastern North Carolina and northeastern South Carolina.

Isolated wetlands in Brunswick, Pender, Columbus and Robeson counties were mapped and documented. The research concluded there are about 50,000 isolated wetlands across the coastal plain averaging about 2/3 of an acre each.

“They’re all fairly small,” Dorney said. “If they get big enough they’ll find a way to get out in which case they would not be isolated. Probably a majority of the state’s isolated wetlands are east of I-95, but nobody really knows. It’s largely a coastal plain thing. My best guess is there are hundreds of thousands of these wetlands in North Carolina that occupy tens of thousands of acres. We just don’t have good data.”

What researchers do know is that, in addition to recharging groundwater, isolated wetlands can store a lot of water. This is important particularly during a tropical storm or hurricane, Dorney said.

University of South Carolina professor Dan Tufford has participated in two EPA-funded studies examining isolated wetlands, including the one with Dorney conducted from 2008-2010.

Tufford has for years been urging South Carolina’s legislators to establish isolated wetlands regulations.

“I have argued in South Carolina until I’m blue in the face,” he said. “If a half an acre is all I can get I’ll take it. If you couple the water quality trends with the biological information and hydrological information and the size assessment we did in the first study it is clear that, although they cover a small area, they appear to have several fairly important functions on the landscape.”

Without a large-scale study, researchers say it’s tough to know with absolute certainty how the depletion of isolated wetlands will impact the environment.

Still, they’re convinced the outcome would not be good.

“There are many critters that depend on these isolated wetlands and they’re going to go away,” Tufford said. “Those environmental functions are going to go away. Getting rid of them all, which is probably what’s going to happen, will be detrimental. It seems pretty clear that isolated wetlands do improve the quality of water that ultimately makes it into a nearby stream. By all means, the connection is there.”

Rather than change the acreage in the current regulations, Dorney suggests changing the rules to reflect the wetland’s quality. The state can assess isolated wetlands and those deemed low quality would have fewer regulations.

“The EMC unanimously passed the isolated wetlands rules in 1996,” Dorney said. “Some of the same people are on the commission today. It’s very concerning because the only mechanism to protect these areas is the state rules. If the state’s not protecting them, nobody will.”