Last of two parts

WILMINGTON — Unlined, decades-old ponds holding more than two million tons of coal ash at Duke Energy’s plant outside Wilmington are some of the first in the state that the utility plans to close.

Supporter Spotlight

Duke will submit to the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources a conceptual closure plan for the coal ash ponds at the L.V. Sutton Steam Electric Plant off U.S. 421 by mid-September, Paul Newton, president of Duke’s utility operations in North Carolina, said during an April 22 meeting of the state Environmental Review Commission hearing.

Paul Newton |

“Once the appropriate permits are received, removing water from the ash basins will be completed in the next 18 to 24 months,” he said, according to a transcript of the hearing.

Closing all 33 ash ponds at Duke’s 14 North Carolina sites could cost billions and take upwards of three decades, he said.

Environmental groups that want Duke to act now say that’s too long given the threat these lagoons, which store 106 million tons of ash in the state, pose to nearby waterways and groundwater.

Earlier this year a Wake County Superior Court judge agreed. Judge Paul Ridgeway on March 6 ordered that Duke take “immediate” action.

Supporter Spotlight

His ruling was issued about a month after a Feb. 2 coal ash spill from a retired Duke plant in the Piedmont coated 75 miles of the Dan River.

Mary McClain Asbill |

The utility and the Environmental Management Commission have appealed. They argue the state does not have the authority to order an immediate cleanup.

In the meantime, federal prosecutors are conducting a criminal investigation into the Dan River spill. Duke and DENR have received more than 20 subpoenas demanding documents and ordering state employees to testify before a grand jury.

The investigation began after questions were raised about a proposed deal between state regulators and Duke to settle groundwater contamination violations at the company’s plants near Asheville and Charlotte by fining the utility a $99,111. The state and utility were also negotiating a settlement for the contamination at Sutton.

Open-Ended Timeline

Duke’s legal troubles do not appear to impede its plans to expedite closing the ponds at the Sutton plant.

Sen. Phil Berger |

Sen. Tom Apodaca |

“We are working now on engineering studies to help determine the most appropriate way to permanently close the basins,” Erin Culbert, a Duke spokeswoman, wrote in an email responding to questions. “This engineering work ensures we select a method or combination of methods that will protect groundwater long-term. The timeline for removal of ash at Sutton, if that option is selected and approved by DENR, would depend on its destination (lined landfill or lined structural fill) and how soon that destination can be prepared and ready to receive the material.”

Closure plans for the basins at Sutton and three other plants are in a bill introduced in the N.C. General Assembly last week by Sens. Phil Berger, R-Rockingham, and Tom Apodaca, R-Henderson.

Senate Bill 729 is similar to an earlier one proposed last month by Gov. Pat McCrory, who retired from Duke after nearly 30 years with the company.

The bill requires closure plans for Sutton to be submitted within 90 days of the bill’s passage. Those plans must include detailed provisions to ensure all ash in the impoundments will be moved to a lined structural fill or to a lined landfill, but the bill allows an “alternative disposition” approved by DENR.

The bill calls for DENR to “establish the priority for closure of all active and inactive” ash basins, but it stops short of specifying how the department should set those priorities. Included in the bill is $1.4 million to fund 19 permanent positions in DENR “to implement this act.”

Grassroots Effort

Environmental groups are taking advantage of mounting public interest in the aftermath of the Dan River spill by encouraging residents and local leaders to pressure the state to do more on the coal ash front.

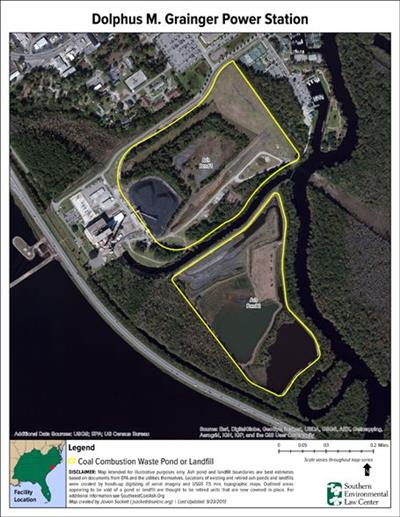

Outlined in yellow are two coal ash ponds at the Dolphus M. Grainger power plant near Conway, S.C., where locals lead a successful case against their utility company, Santee Cooper, to remove all ash waste. Source: Southern Environmental Law Center |

“While we work in the courts the state can and should act,” Mary Maclean Asbill, a senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center, said during an April 28 forum hosted by the Cape Fear Group of the N.C. Chapter of Sierra Club.

More than 50 people attended the meeting at a local radio station in downtown Wilmington, where they were encouraged to write Wilmington’s mayor, city council and New Hanover County commissioners.

Zachary Keith, the N.C. Sierra Club lead organizer, told the audience that Duke cannot be allowed “to kick the can down the road.”

He and Kemp Burdette, the Cape Fear Riverkeeper, earlier this year asked the Wilmington City Council to adopt a resolution urging the state to enforce the cleanup of ash basins.

Council members, most of whom toured the Sutton plant earlier this year, took no action.

“We can learn from this and say look, we need to not let this happen again here,” Burdette said. “We want these things moved away from waterways.”

Keith talked about how residents in Conway, S.C., a town about 90 minutes south of Wilmington, got involved in a fight to stop river and groundwater pollution from ash basins at a local power plant. The utility, Santee Cooper, agreed in a settlement to remove all ash waste from its Dolphus M. Grainger Power Station away from the Waccamaw River. The company also committed to removing ash at two other stations over the next 10 to 15 years.

South Carolina Electric and Gas made a similar commitment in 2012, agreeing to remove all 2.4 million gallons of ash from its plan on the Wateree River near Columbia.

Wilmington resident Robert Miller said after the forum that he wasn’t ready to write his local leaders just yet.

“I don’t know what I’ll do, if anything,” he said. “I’m not a big environmentalist, but every now and then I get fired up. I certainly support the idea of the state putting a timeline on clean-up efforts. I thought this is the kind of stuff that happens in the western part of the state. I didn’t realize that the problem was so severe and it was so close.”