First of two parts

An aerial view of the U.S. Fishery Laboratory on Pivers Island in the 1940s. Photo History of the Federal Fisheries Laboratory at Beaufort, North Carolina, 1902-1954` |

BEAUFORT — A collective shudder went through this seaside community when the news broke in March that the 115-year-old federal fisheries lab just across Gallants Channel on Pivers Island might eventually close the doors because of budget cuts.

Supporter Spotlight

After all, the venerable lab run by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Fisheries Service is not just the second-oldest of its kind in the nation, it’s also the cornerstone of what one of its former directors, Ford “Bud” Cross, calls a marine science “powerhouse,” the first outpost of what became a synergistic conglomeration of marine expertise in Beaufort and neighboring Morehead City that some think is unrivaled on the East Coast.

And, Cross said recently, it’s more than that: The lab is also – and has been for many years – a key contributor to the economy of the area and also a major contributor to its very culture.

Ford “Bud” Cross |

Many of the lab’s scientists retired here, Cross said. They wouldn’t leave if the lab shut down, he said, but the loss of the steady influx of new professional blood into the area would rob the county of a rich vein of well-educated men and women who volunteer their time and talents to things as disparate as youth soccer and other sports, wildlife advocacy and protection, community theater, education and countless social causes.

Those scientists serve on committees and commissions and are active in organizations like the N.C. Coastal Federation, the Sierra Club and Carteret County Crossroads. Some of its personnel and visitors also have been major contributors nationally and even internationally. The nearby Rachel Carson Estuarine Reserve, for instance, is named for the woman who visited the lab and decades later wrote Silent Spring, the 1962 book that launched the modern environmental movement by exposing the environmental dangers of pesticides, especially DDT, and its dramatic effect on birds.

The lab’s closure, in short, would leave gaping holes.

Supporter Spotlight

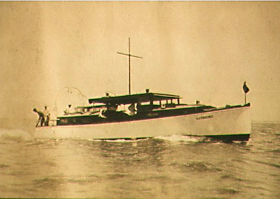

The Sandpiper, a 46-foot research cruiser, served the Beaufort lab from 1928 until the beginning of World War II. Photo Source: “A History of the Federal Biological Laboratory at Beaufort, North Carolina 1899-1999” |

“It’s always been a close-knit community,” Cross said, a home to dedicated scientists who enjoy each other’s company. But those people have never been insular, he added. Although the lab is on an island, between Morehead City and Beaufort proper, those who work there have never felt separated by water or anything else from the fishermen and business owners around them.

“People from the lab have always been involved,” said Cross, who was a key member of the Morehead City Planning Board during some of the 15 years he served as lab director. “Many of us have always felt we had something to give to the place we live, and we’ve tried to do that.”

Cross arrived at the lab in 1967, and some of those who arrived in the same period are also still around. The retirees get together semi-formally once a year for lunch, but they see each other everywhere. And most feel a sense of real pride, a bit of ownership in the marine science community, because without the NOAA lab, there might never have been counterparts, like the Duke University Marine Lab, also on Piver’s Island; the N.C. State Center for Marine Science and Technology, or CMAST, in Morehead City; and the UNC Institute of Marine Science, also in Morehead. NOAA, after all, was there first, by a wide margin, and so is partly responsible for the others.

First Lab on Front Street

The lab opened in 1899 in a house on Front Street in Beaufort and moved to its current location on Pivers Island, then just outside town, three years later. The roots go back even farther.

According to a history put together a decade ago by another now-retired lab employee, Charles Manooch, Beaufort became a field station for people interested in marine biology following the visits of zoologists Theodore Gill and William Stimpson in 1860. Elliott Coues and H. C. Yarrow, Army surgeons stationed at Fort Macon at the tip of nearby Atlantic Beach, compiled lists of mammals, birds, reptiles, fish and mollusks, which were published in a series of articles in the 1870s. In the 1880s, professors and students from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore maintained a station in a rented house and used the area as a summer teaching and research facility.

The Beaufort lab occupied the Gibbs House on Front Street from 1899-1901. Photo Source: “A History of the Federal Biological Laboratory at Beaufort, North Carolina 1899-1999” by Douglas Wolfe |

It’s easy to see why. As Cross noted, there’s no place on the East Coast like Beaufort. It has easy access to deep water and to estuaries and is near the confluence of all East Coast fisheries. It’s near the southern end of the range of many south Atlantic species and the northern end of the range of many other species. Marine mammals are plentiful, as are all kinds of seabirds.

According to the history by Manooch, the federal government became interested in local fisheries when Congress passed a joint resolution in 1871 creating the Office of Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries.

Spencer F. Baird was the first commissioner, Manooch wrote, and for the next 10 years he and other scientists at the new Bureau of Fisheries studied the fish species in the waters around Beaufort, mostly in the summer. It was not until 1899, however, that a permanent fisheries laboratory was established, thanks largely through the efforts of Henry Van Peters Wilson. A professor at the University of North Carolina, Wilson received $300 from the U.S. Fish Commission to rent the Duncan house on Front Street and to buy a couple of boats and hire some help in the summer. Congress a year later authorized the establishment of a year-round U.S. Fish Commission marine laboratory at Beaufort.

The Beaufort lab became the second federal fisheries laboratory in the country. Only the lab in Woods Hole, Mass., established in 1885, is older.

Move to Pivers Island

Congress didn’t appropriate any money to buy land for the new lab, but again Wilson came to the rescue, Manooch wrote. He raised $400 to buy three acres on Pivers Island. Among the donors were Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and the state universities in North Carolina, Virginia, Georgia and South Carolina.

Wilson became the first laboratory director and was responsible for planning the main building, which served scientists and investigators for more than 50 years.

The lab at the fishery station as it appeared about 1915. The building in the foreground is a turtle hatchery house. Photo source: “A History of the Federal Biological Laboratory at Beaufort, North Carolina 1899-1999” by Douglas Wolfe |

It was, Manooch wrote, “founded with a regional responsibility to learn the life histories of marine animals and plants, their relations to each other and the environment, their resource potential, the effects of man on their abundance, and methods for their scientific culture.”

The scientists moved in May 1902 while construction was still going on. The wooden, two-story building was 180 feet long and contained a laboratory, aquarium, office, twelve bedrooms, halls, bathroom and storerooms. There were also a mess hall, a power house, a boathouse, a fuel shed, minor outbuildings, and 80-foot-long pier.

Until 1908, the lab was open only from May to September. About 15 scientists came each summer, and their studies varied from the collection and identification of fish and invertebrates to microscopic examination of tissues and organs. Visiting scientists were allowed to follow whatever studies they wished, although the Bureau of Fisheries personnel were concerned principally with the fishes collected by the Research Vessel Fish Hawk and the artificial rearing of oysters, clams and sponges.

One of the earliest and most interesting of the lab’s s areas of focus was turtle propagation. From 1909 to the 1940s, according to Manooch’s work, nearly 250,000 terrapins were raised at the lab and released in the marshes of the Carolinas, Virginia and Georgia.

The Navy took the lab during World War I, using it to investigate the fouling of ships’ bottoms.

After that war, Manooch wrote, times were tough. “The Commissioner of Fisheries in his annual reports complained about the ‘impossibility of filling the vacant positions with competent men at the salaries available.’”

Rachel Carson Arrives

Rachel Carson visited the lab in 1938 to do research on the islands across from Beaufort. Today those islands are known as the Rachel Carson Estuarine Reserve. Photo source: Yale Collection |

The laboratory was severely damaged by a hurricane on Sept. 16, 1933, but repairs were made, thanks to funds provided by the Public Works Administration. Significantly, those funds also paid for the first bridge to the island, a one-lane wooden structure.

Carson, an aquatic biologist with the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, arrived soon after. A Pennsylvania native, she came to the fisheries station in Beaufort in 1938 and did research on the islands that make up the coastal reserve that bears her name. Her observations of shorebirds in the area inspired her 1941 book, Under the Sea-Wind, and she wrote about Beaufort’s estuarine region in 1955’s The Edge of the Sea. She died of cancer in 1964, but not before writing her seminal Silent Spring, which eventually led to a U.S. ban on DDT.

The lab is headquarters for staff of the N.C. Coastal Reserve and Natural Estuarine Research Reserve. Teacher training workshops take place there.

Doug Wolfe, who left the lab in 1975, went to work for NOAA in Colorado and Washington, D.C., and wrote a history book to commemorate the Beaufort lab’s 100th anniversary. He also retired in the county. In an interview, he said Carson, while not affiliated with the lab while she was in the area, did have a connection, through Elmer Higgins, who was there in 1924 while actually designated as director of the Key West lab of the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries.

Higgins rose through the ranks and was appointed chief of the Division of Scientific Inquiry in Washington. He hired Carson, who visited but didn’t work for the lab in Beaufort.

Wednesday: The lab comes of age