First of two parts

The breakers looked like droves of a thousand white horses of Neptune, rushing to the shore, with their white manes streaming far behind; and when, at length, the sun shone for a moment, their manes were rainbow-tinted. — Henry David Thoreau

Supporter Spotlight

Sitting on a dune near the north end of Ocracoke Island, I studied Thoreau’s words, written more than 150 years ago, about the coastline of Cape Cod. I could have written the same today about the view that stretched before me.

I used to walk Ocracoke Island’s ocean beach each winter, having someone drop me off near the Hatteras ferry on the north end of the island. I’d walk all day, alone, and then bum a ride back to the village on the other end of the island. There is something primeval about seeing the ocean and shoreline expand before you without the refuge of a truck waiting nearby. I would make mental notes and later record them in my journal.

A 1908 edition of Thoreau’s book “Cape Cod.” Photo: University of Rochester |

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862), American author and poet. |

It was after I began reading Thoreau’s classic account, “Cape Cod,” and realized that he had done exactly the same thing, walking the length of the Massachusetts cape, that I thought of walking the length of Ocracoke again. This time I decided to carry Thoreau’s book with me and compare his experiences with my own.

Cape Cod is much longer than Ocracoke Island, so Thoreau broke his walk into several segments, taking his first walk in 1849, his last in 1857. I decided to break up my walk similarly to have more time to sit down along the way and reflect on his and my experiences.

Thoreau wrote, as his reason for walking, that, Wishing to get a better view than I had yet had of the ocean […] I have spent, in all, about three weeks on the Cape; walked from Eastham to Provincetown twice on the Atlantic side, and once on the Bay side also, excepting four or five miles, and crossed the Cape half a dozen times on my way; but having come so fresh to the sea, I have got but little salted.

Supporter Spotlight

It was on a brisk day in January that I set out to walk, having asked my friend Rita to join me for the first part. We rode to the north end of the island, leaving my truck at the Pony Pens; she parked near the ferry station. We started out along a path through the sand dunes. With heavy cloud cover and a brisk wind rushing down the beach, it was ferociously cold.

On Thoreau’s first day of walking, along the Plains of Nauset, he and a companion met a storm. We walked with our umbrellas behind us, since it blowed hard as well as rained, with driving mists. Having seen plenty of storms at Ocracoke, I had no desire to encounter one today. I hoped the weatherman had been right when he said the rain would hold off until night.

“Are you sure you want to do this, Pat?” Rita asked me. I wondered myself, but told her that I would kick myself if I gave up.

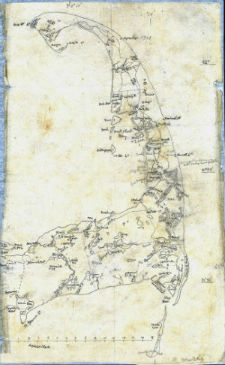

This map of Cape Cod was one of the many maps of the cape that Thoreau drew. Drawing: Cape Cod Free Library This map of Cape Cod was one of the many maps of the cape that Thoreau drew. Drawing: Cape Cod Free Library |

I gazed at the body of water separating us from Cape Hatteras. This inlet has opened and closed several times through the centuries, the last time being in 1846, when a storm breached the island. Now the Hatteras Inlet provides access for boats heading from Pamlico Sound to the Atlantic Ocean, and is a corridor for ferries traversing the short distance between the islands. We caught sight of an Ocracoke-bound ferry wending through the channel and also a fishing trawler heading through the Inlet and out into the ocean.

Fishing was one of the topics Thoreau wrote about, saying that it had replaced the production of salt, which once provided livelihoods for Cape Cod residents. Soon after passing the Highland Lighthouse, he described how he saw countless sails of mackerel fishers abroad on the deep, one fleet in the north just pouring round the Cape, another standing down toward Chatham.

Across the inlet we could see the water tower of Hatteras Village as well as that long stretch of sand known as the Point that extends from Cape Hatteras almost to Ocracoke. Thoreau said, referring to the name Cape Cod, that, I suppose that the word Cape is from the French cap; which is from the Latin caput, a head. My dictionary says that a cape is “a piece of land projecting into water.” I guessed that the strip of sand we stood on was technically a cape.

Rita and I walked along a scraggly shoreline where small, twisted and lifeless trees protruded from banks, and Sargassum weed, blackened by its tumultuous journey to land, draped the sand. We hopped across a stream of flowing water that gushed from a small pond where several species of ducks dabbled. We wandered across salt flats, picking up shells and bits of jetsam, and came across the remains of several jellyfish, what locals here call “jellyballs.” Even in death their bell shape and lovely translucence drew my attention.

Thoreau wrote of coming across similar forms on Cape Cod, saying that The beach was also strewn with beautiful sea-jellies; which the wreckers called sun-squall, one of the lowest forms of animal life, some white, some wine-colored, and a foot in diameter. I at first thought that they were a tender part of some marine monster, which the storm or some other foe had mangled. What right has the sea to bear in its bosom such tender things as sea-jellies? Strange that it should undertake to dangle such delicate children in its arm.

Finally Rita and I arrived at the sea. The elevation at Cape Cod is higher than Ocracoke’s, but otherwise Thoreau’s description could have been ours: […] crossing over a belt of sand on which nothing grew […] we suddenly stood on the edge of a bluff overlooking the Atlantic […] The waves broke on the bars at some distance from the shore, and curving green or yellow as if o […] so many unseen dams, ten or twelve feet high, like a thousand waterfalls, rolled in foam to the sand. There was nothing but that savage ocean between us and Europe.

Pat Garber walked the beach of Ocracoke Island (above) and said, “I studied Thoreau’s words, written more than 150 years ago, about the coastline of Cape Cod. I could have written the same today about the view that stretched before me.” Photo: Sam Bland |

It was nearing time for Rita and me to part ways, so we found a protective dune to shield us as we ate our tuna fish sandwiches. She returned to her car and I, clutching my jacket tightly around me, set out in earnest, following this majestic ribbon of sand where, in Thoreau’s words, everything told of the sea.

The wind was at my back, not a hard wind but one that sent fine grains of sand scattering ahead of me, low to the ground, and produced the illusion that the land itself was in motion.

Thoreau described the wind as he and his companion trekked across what he called the Cape’s wrist; a migrating sand-bar in the air, which has picked up its duds and is off, to be whipped with a cat, not o’nine-tails, but of a myriad of tails, and each with a sting to it […] The sound of the breaking waves was like music, a very inspiriting sound to walk by, filling the whole air, that of the sea dashing against the land.

Brown pelicans are often seen “surfing” the air current above waves along North Carolina’s coast. Photo: Sam Bland |

Before long I noticed that a pod of bottlenose dolphins was making its way along the shore, their graceful forms rising and falling just on the other side of the breakers. The ocean was a busy place here with brown pelicans riding air currents above the waves, herring gulls splashing into the waves and gannets — big, elegant white birds with black wing tips — diving a little farther out. The fishing must be good here, I decided. I set my pace to keep up with the dolphins, slowing down when they ran into better fishing, hurrying up when they moved ahead of me. I stayed beside them for about a mile, at which time they and the feasting birds disappeared. I think my traveling pals must have turned around and returned to the richer fishing grounds.

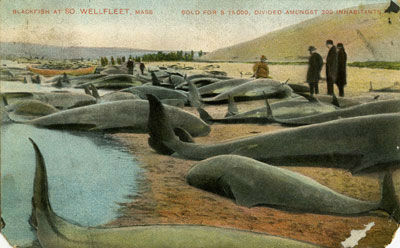

Thoreau’s encounter with cetaceans was not so pleasant to read about. Whaling was legal in 1849 and an important source of income on the Cape. Thoreau described the harvest of “blackfish” (probably similar to what we call pilot whales, a kind of dolphin) which he came across near Provincetown: In the summer and fall sometimes, hundreds of blackfish, fifteen feet or more in length, are driven ashore in a single school here. I witnessed such a scene in July, 1855 […] I counted about thirty blackfish, just killed, with many lance wounds, and the water was more or less bloody around […] The fisherman slashed one with his jackknife, to show me how thick the blubber was,–about three inches; and as I passed my finger through the cut it was covered thick with oil. The blubber looked like pork, and this man said that when they were trying it the boys would come sometimes round with a piece of bread in one hand, and take a piece of blubber in the other to eat with it.

“Trying” the blubber meant, I knew, heating it to render the oil. Here on Ocracoke, dolphins had been harvested in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and their blubber “tried” for lamp oil. Try Yard Creek, one of the saltwater creeks that partially bisects the island, which I would be passing today, received its name from this practice.

Wildlife is abundant on Ocracoke Island. Garber writes about the animals she sees along her beach walk, such as a pod of bottlenose dolphins fishing in the breakers. Photo: Sam Bland |

Other than Rita, I saw no other humans since leaving the village. Having the beach to myself was wonderful, and I found my thoughts reflected in Thoreau’s description of his1857 walk: […] that solitude was sweet to me as a flower. I sat down on the boundless level and enjoyed the solitude, drank it in, the medicine for which I had pined.

The shore I walked now was barely recognizable compared to the one I traversed before, but that came as no surprise. Ocracoke’s shoreline changes shape with every storm that churns her sands. Barrier islands are always on the move, migrating westward toward the mainland and sharing sand up and down the beaches. It is not a new phenomenon, as reflected in the following observation made by Thoreau: As I looked over the water, I saw the isles rapidly wasting away, the sea nibbling voraciously at the continent. Later in the book he remarked, Perhaps what the Ocean takes from one part of the Cape, it gives to another,–robs Peter to pay Paul.

There were not as many birds along the stretch of beach I approached now. I saw a great black-backed gull sitting near the dune line, and swooping across the water, too far away to identify, a few gulls searching for fish. Thoreau wrote about gulls he saw on the beach at Cape Cod in October, 1849, saying Mackerel-gulls were all the while flying over our heads and amid the breakers, sometimes two white ones pursuing a black one […] and we saw that they were adapted to their circumstances rather by their spirits than their bodies. Theirs must be an essentially wilder, that is less human nature, than that of larks and robins.

As I followed the shoreline, I became intrigued by a proliferation of what looked like artistic drawings in the sand in varying shapes and colors. They were somewhat circular but very irregular, sometimes connected, with two or three rings composed of differing colors of sand. I had seen them before and knew that their formation was due to interactions of wind, water and slope with sands of differing weights and textures. With such variety and somewhat ghoulish shapes, it was easy to imagine an artistic sense of humor behind their design.

This 1901 postcard shows pilot whales, a type of dolphin, stranded or driven onto a beach at Cape Cod, similar to what Thoreau saw at Provincetown. Photo: American Antiquarian Society This 1901 postcard shows pilot whales, a type of dolphin, stranded or driven onto a beach at Cape Cod, similar to what Thoreau saw at Provincetown. Photo: American Antiquarian Society |

Thoreau did not describe the same sand art I saw, but a similar phenomenon which I have often noted in my beach explorations. Talking about beach grass, he wrote: As it is blown about by the wind, while it is held fast by its roots, it describes myriad circles in the sand as accurately as if they were made by compasses.

Farther down the beach, I came upon the timbers of an old shipwreck, its bones laid open to view by recent wind and water. I turned to Thoreau’s words, written in 1849: The sea, vast and wild as it is, bears thus the waste and wrecks of human art to its remotest shore. There is no telling what it may not vomit up […] perhaps a piece of some old pirate’s ship, wrecked more than a hundred years ago, comes ashore to-day.

As I neared the place where I had left my truck, I noticed that the sky had grown darker. My brisk walk and heavy jacket had kept me warm, but now I felt raindrops patter against my jacket. So much for the weatherman’s prediction of a dry day! Oh well, as Thoreau had begun his day walking in the rain, it seemed fitting that I end mine the same way. He had written: The reader will imagine us, all the while, steadily traversing that extensive plain […] and reading under our umbrellas as we sailed, while it blowed hard and mingled mist and rain.

I was anxious to reach shelter, but I took a moment more to stand and gaze out across the water. The tide was coming in, and each wave, as it thrashed its way toward land, seemed intent on out-racing the last. Beyond this stretched the unwearied and illimitable ocean.

Wednesday: “The foam ran up the sand… as regularly as the master of a choir beats time with his white wand.”