No one really how many clams Elmer Willis shipped out of this now ramshackle building in Williston, but it was an economic force and a proud symbol of the region known as Down East. Photo: Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center No one really how many clams Elmer Willis shipped out of this now ramshackle building in Williston, but it was an economic force and a proud symbol of the region known as Down East. Photo: Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center |

WILLISTON – There’s really no telling how many clams and scallops Elmer Willis shipped out of the now derelict cinder block building that sits on the bulge of a sharp curve along U.S. 70 in eastern Carteret County.

“Millions, maybe?” speculates his daughter Nancy Lewis.

Supporter Spotlight

Enough, notes Jonathan Robinson, to make Willis Brothers Seafood for decades one of the main employers in this end of the county. “My aunt and uncle worked there,” says Robinson, the chairman of the county commissioners and a former commercial fisherman from down the road in Atlantic. “A lot of people did. Man, you had to see those ladies’ hands a-flyin’ shucking those clams.”

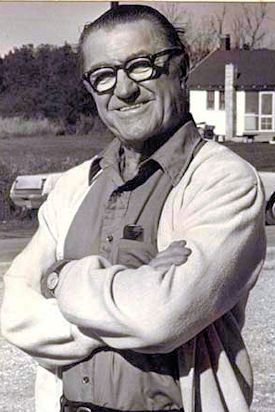

Elmer Willis, The Clam King. Photo: Nancy Lewis Collection, Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center Elmer Willis, The Clam King. Photo: Nancy Lewis Collection, Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center |

There’s a picture of Willis on the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center web site. He’s fit and smiling and dapper. Arms folded across his chest and dark hair slicked back, Willis looks almost regal. It’s the pose of The Clam King, which is what they called him back in the day.

It’s all gone now, of course. Willis died in a car wreck in 1977. The clam house died with him. The thriving fishing industry that supported them both is now a shadow of itself. All that’s left of that glorious time is the sad hulk of an abandoned building – its roof rotting, its windows gone, its walls obscured by weeds and trees. What was once a proud symbol of a region they call Down East and of the fishing folks who live there is now, frankly, an eyesore.

Karen Willis Amspacher thinks The Clam King and the heritage he represents deserve better. A native of the Down East community of Harkers Island, she is the director of the museum and a fierce protector of local culture.

“This place was an institution,” Amspacher says as we walk to the back of the old building, through the weeds and across the decades of discarded clam shells that cover the ground. “My hope is that the people of Down East can hold on to it. It may never be a clam house again but we may be able to adapt it to another use.”

Supporter Spotlight

A move is afoot to do just that. In the end, it will likely take the Marines and a bunch of ding-batters – local parlance for people who ain’t from around here – to make it happen, but so be it.

The Conservation Fund, which has saved more than seven million acres of land and water all across the country, is trying to buy the old clam house and the 90 or so acres – marsh mostly – that come with it. The fund is working with the Down East Council, a group of volunteers who are involved in an initiative coordinated by Amspacher called Saltwater Connections. The four-year-old effort aims to protect cultural heritage and sustain livelihoods and natural resources Down East and on Hatteras Island on the Outer Banks.

The fund last week submitted a request for $130,000 to the N.C. Clean Water Management Trust Fund, a state agency that provides grants to preserve ecologically sensitive land. The Marine Corps, explains Justin Boner, may pay the remainder of the $185,000 purchase price for the clam house from a program to prevent development from encroaching on its bases and training areas.

“The Marines are always concerned about tall structures, such as cell towers,” says Boner, the fund’s director of North Carolina real estate.

Fisherman unload bushels of clams onto Willis Brothers dock in the 1940s. Photo: Nancy Lewis Collection, Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center Fisherman unload bushels of clams onto Willis Brothers dock in the 1940s. Photo: Nancy Lewis Collection, Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center |

The clam house property, he says, sits under the convergence of three flight paths used by aircraft from the Corps’ air station in Havelock.

If all the pieces fall into place, the fund could own the property by the end of the year. It would then donate it to the county for public use.

No one knows just yet exactly what to do with it. There’s talk of picnic tables and a kayak launch, maybe even a public restroom. There’s not one on U.S. 70 along its 40 or so miles through Down East. The old clam house itself, though, would likely have to come down.

“Hopefully, we’ll be able to develop some public access there,” Robinson says. “It’s the most picturesque spot in the eastern end of the county.”

Right across Williston Creek, the waterfront site commands a sweeping view of Jarrett’s Bay. Historic Davis Island sits on the horizon, where the bay empties into Core Sound. A good pair of young eyes can see the roof of the old hunting lodge above the tree line. The rest of us need binoculars.

Lewis hopes something is done with her Daddy’s old place. She’s 77 now and it pains her to drive by it. She sits a few miles away, on the back porch of her house in Davis. Spread out on the table in front of her or piled in a box at her feet are old family photographs, newspaper articles and other bits and pieces she has collected that tell of a happier time for the old clam house.

In 1960s the clam house was in its prime, selling thousands of clams a week. Photo: Nancy Lewis Collection, Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center In 1960s the clam house was in its prime, selling thousands of clams a week. Photo: Nancy Lewis Collection, Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center |

“Here, take a look at this,” Lewis says as she hands me a page from a Willis Brothers receipt book from the mid-1940s. The handwritten numbers tell the story: 22,000 clams, 50,000 clams, 78,000 clams, 100,000 clams. That’s for one week.

“There were a lot of clams that went out of that building,” she says. “People just don’t realize it.”

A native of Williston, Willis quit school after the eighth grade to help his father fish commercially. He left for Norfolk where he worked for a time as an engineer on boats, but he came home to stay in 1939, bringing with him a wife – Pearl Smith of Atlantic – and a 2-year-old daughter, Nancy. Another daughter, Beverly, would be born later.

Willis opened a general story on the big curve just past the bridge crossing the creek. It housed the post office, where Pearl was the postmistress for many years. He also opened a boat-building shop near the store and then in the early 1940s, Lewis says, started the seafood business with his brother Wesley, who Willis later bought out.

Clams became the company’s main product after Heinz Soup came a calling. For years, Willis provided every clam that Heinz put in its cans of chowder. Again, to the receipt books: 5,000 gallons of clams were shipped to Heinz’s plant in Pittsburg every week in the mid-1940s. Willis got about $2.20 a gallon.

Gov. Kerr Scott, center, attends one of Elmer Willis’ clambakes. Photo: Nancy Lewis Collection, Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center Gov. Kerr Scott, center, attends one of Elmer Willis’ clambakes. Photo: Nancy Lewis Collection, Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center |

Soon after Willis signed the Heinz contract, Pearl bought a can of the company’s chowder and served it to Willis one night without telling him what it was.

“Do you know what you’re eating, Elmer?” she finally asked.

“I sure do,” he responded. “It’s vegetable soup.”

“I will always remember that,” Lewis says, still chuckling at the memory. “There were so few clams in that chowder that Daddy thought it was vegetable soup.”

But he kept sending clams to Pittsburg.

He also shipped them to Cleveland, Ohio, which for some odd reason is known as the Clambake Capital of America. Every three days each fall, 100,000 little necks arrived in Cleveland from Williston.

Some of the clams stayed closer to home. Willis sponsored a clambake one fall to raise money for a cafeteria at his daughters’ public school in Smyrna. They became yearly fundraising events for the local schools.

“They were a big deal,” Lewis remembers. “A thousand people would come. I’ve got pictures of governors at the clambakes.”

Nancy Lewis, the daughter of Elmer Willis, is surrounded by memorabilia of her father’s seafood business. Photo: Frank Tursi Nancy Lewis, the daughter of Elmer Willis, is surrounded by memorabilia of her father’s seafood business. Photo: Frank Tursi |

Willis also perfected a scallop-shucking machine that he later patented, against Lewis’ advice. It would be too expensive and too difficult to defend, she thought. “But he just had to have that patent,” she says.

Willis had a heart attack in the 1960s. Lewis visited her father one day in the hospital in Chapel Hill. On a table beside him was a huge, gorgeous flower arrangement from the patent attorneys. “That’s a $65,000 bouquet,” Willis cracked.

After the car accident, Pearl sold the clam house, but the new owners couldn’t keep it going for long.

“A business is sort of in a man’s head,” Lewis explains. “It’s not the buildings. Daddy had a vision in his mind. If the clams were dwindling around here, he’d jump in a car and drive all over to get clams. That’s the way he was.”

The clam house closed, and a fire in the 1990s destroyed the old store and boat works.

All that’s left is a ramshackle building probably beyond saving, but Amspacher will try. “I have to try and save it,” she says. “I’d be happy with one wall that we can paint Elmer’s picture on. But even if it all ends up as a pile of rubble, we have to keep it as a memorial to Elmer.”