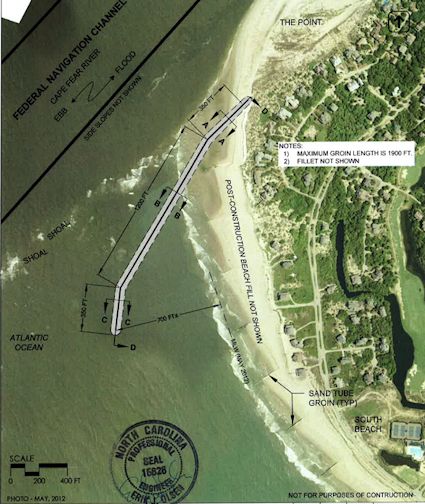

Bald Head Island property owners want to build a terminal groin almost 2,000 feet long to go along with the 16 smaller groins that they built along the South Beach to control erosion. Photo: Village of Bald Head Island |

BALD HEAD ISLAND — A small jetty almost 2,000 feet long is the only viable option Village of Bald Head Island officials say will slow chronic, sometimes dramatic, erosion on the island’s western shore.

Later this year the village will likely know whether the Army Corps of Engineers Wilmington District agrees.

Supporter Spotlight

The Corps had planned to hold a public hearing today on its draft environmental impact statement on the so-called terminal groin, but that hearing was cancelled last night because of the weather. A new hearing date has not been set.

The meeting would be the next step in the Brunswick County island’s pursuit to obtain a Coastal Area Management Act major permit to build a groin, which is a small jetty meant to control erosion.

Such structures were once banned on N.C. beaches because they tend to increase erosion on nearby beaches, but the N.C. General Assembly passed a bill in 2011 to allow them at four inlets. Figure Eight Island, Ocean Isle Beach and Holden Beach have joined Bald Head in applying for the groins. All the projects are in various stages of Corps’ environmental review. None has yet applied for a state permit.

The 740-page page draft EIS for Bald Head examines six alternatives to reduce beach erosion on South Beach, the Point and West Beach, all areas that have experienced persistent sand loss over the last 18 years.

In the alternative favored by the village, a wall of large granite armor rock of different sizes would extend 1,300 feet into the water perpendicular to the shore to trap drifting sand. The village wants to continue maintaining 16 smaller groins made from fabric tubes filled with sand along the westernmost portion of South Beach.

Supporter Spotlight

The tubes, spanning anywhere from 250 feet to 350 feet long, were initially built in 1995, then entirely replaced a decade later and again in 2010.

This so-called groin field is one of a variety of erosion-control tools the village has used over the years to fend off accelerated erosion that village officials say is a result of the beach’s proximity to the Wilmington Harbor Channel.

“Because the island sits adjacent to the shipping channel, it experiences constant erosion,” village spokeswoman Karen Ellison wrote in an email. “The terminal groin slows that process and so should ease the burden on the Corps and should keep the beaches more stable, longer. But it is not a panacea … we will still need dredging and erosion will continue; just at a slower rate.”

The corps of engineers routinely dredges the shipping channel, a vital economic waterway used by ships heading to and from the state port in Wilmington.

The village, along with other area beaches, including Caswell Beach, began getting sand from the dredging beginning in 2000 with the implementation of the Wilmington Harbor Sand Management Plan.

The Corps has periodically pumped beach-quality sand from the channel along those beaches at the federal government’s expense. It’s a process that has benefited those towns with, perhaps, the exception of Bald Head, which sued the Corps in 2011 and where some argue the corps is responsible for creating the erosion problem.

Suzanne Dorsey |

Mike Giles |

“We have an artificial, non-natural engineered problem with the channel,” said Suzanne Dorsey, executive director of the Bald Head Island Conservancy. “We have no control over that channel. The sand on Bald Head collapses into that channel. It’s not sea-level rise causing this. It’s erosion caused by a deep- level channel cut by the Army Corps of Engineers. A terminal groin will help the island slow down the rate of sand loss a little bit more.”

Mike Giles, a coastal advocate in the N.C. Coastal Federation’s Wilmington office, questions just how effective a terminal groin will be in reducing the rate of erosion on the island.

“Our concern about these terminal groins is they say they’re permeable. At what rate? How will that happen? Will the terminal groin become clogged?” he asked. “A lot of inlets are dredged along our coast. We haven’t seen the science that says these terminal groins will work along our coast at these dynamic inlets.”

The federation opposes the construction of hardened erosion structures on the beach. Giles said the federation will submit a statement reiterating its opposition before the corps of engineers’ written comment period ends Feb. 24.

Dorsey, who is also a member of the N.C. Coastal Resources Commission, said that while she understands objections to terminal groins, it is the best alternative for the island.

“I think it makes sense to oppose it,” Dorsey said. “We hate it. We all hate the groins. But what is the alternative to a community that is being impacted by an engineered problem? It’s a risky solution, but the groin is the only option for Bald Head. It acts as a dam, which is what the village of Bald Head needs. They’ve explored every option. This is their last option. If there was a way out of it I promise you they’d take it.”

Dorsey has been with the conservancy for nine years, during which environmentally conscious property owners and village leaders have asked her what natural alternatives the island has in protecting its shore.

“The only answer I can give them is this is an artificial situation,” she said. “You’re working with a group of people who have sacrificed, invested and made really good environmental choices for decades. If you’re going to live on a barrier island this is the best place to live.”

Property owners whose homes were built where the worst of the erosion is occurring built 300 yards back from wet sand behind 100-year-old dunes with established vegetation, Dorsey said.

Those dunes were destroyed in 2009 after a dredge sucked sand from the channel, she said. That sand was later pumped onto Oak Island.

The village filed a lawsuit against the corps of engineers in late 2011, arguing the corps failed to honor its commitment to protect beaches adjacent to the channel from adverse effects of dredging and restore sand to those beaches.

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in Richmond last year upheld an earlier dismissal of the suit, saying the village’s complaint lacked “subject-matter jurisdiction.”

“The village is at this point because the Army Corps won’t stick to their agreement,” Dorsey said.

The village has paid for expensive monitoring that examines possible unintended consequences associated with the construction of a terminal groin, such as how waves bounce off of these structures, she said.

The island’s property owners will be assessed fees in order to pay for the construction and maintenance of the terminal groin if it’s approved.

Caswell Beach Mayor Harry Simmons said he supports the village’s plans to build the terminal groin.

Simmons said he believes Caswell Beach will continue to get its fair share of sand from harbor maintenance projects regardless of the existence of a terminal groin.

“We don’t have any concern about the terminal groin itself,” he said. “It is the only solution. We’re very much in favor of Bald Head moving forward with this project.”