OCEAN — Today more than 63,000 acres of shellfish and swimming waters in coastal North Carolina are legally impaired because of polluted stormwater runoff. It wasn’t always that way.

Supporter Spotlight

Changes to the landscape over the last 40 years to create fields for agriculture and highways, shopping centers and subdivisions for cities and towns have changed the way water moves across the surface of the ground, or what a scientist might call the natural hydrology. Unable to penetrate asphalt and concrete, rain water runs across these hard, impervious surfaces. Or it drains into ditches dug along farm fields. Either way, this stormwater collects bacteria before draining into surrounding bodies of water. The volume and rate of stormwater runoff have dramatically increased, bringing unacceptable levels of bacteria into coastal waters.

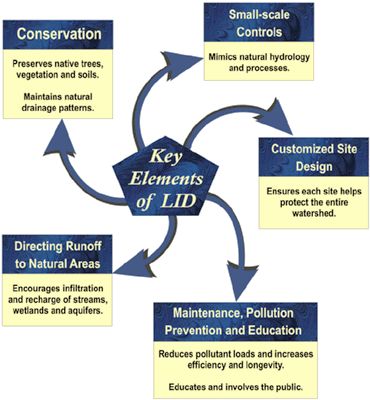

Source: National Institute of Building Sciences |

This is not a problem unique to North Carolina. Many coastal communities throughout the United States are facing the same water-quality impairments. In response, the N.C. Coastal Federation has been working over the last year on an online Watershed Restoration Planning Guidebook.

Soon to be released, the guidebook is the first of its kind to provide clear, detailed guidance to local governments on how to develop a watershed restoration plan that improves water quality by reducing the volume of stormwater runoff. The concept is relatively new and may expedite restoration efforts at a lower cost.

While it presents a method and philosophy that could be adapted to coastal watersheds throughout the country, the guidebook provides resources specific to North Carolina. Also, it targets those smaller portions of watersheds that flow directly into shellfish or swimming waters. By focusing on smaller drainage areas, local and state governments can make smaller changes for lower costs. The result can have significant benefits, including the reopening of closed shellfish waters and a decrease in swimming advisories.

Supporter Spotlight

A group of nine graduate students interning with the federation’s Coastal Advocacy Institute put together the first draft last summer under the direction of Ana Zivanovic-Nenadovic, the federation’s program and policy analyst.

“This is one of the first efforts to put numerical value to the volume of stormwater reduction needed for the improvement of water quality,” she said.

Traditionally, methods for reducing the amount of pollutants in impaired waters have been to either eliminate the sources of bacteria—a feat that is nearly impossible given that most of it comes from wildlife and pet waste—or expensive stormwater treatments at the end of pipes that remove contaminants before water is released into water bodies.

The federal Clean Water Act requires that states set goals to reduce pollutants to impaired waters. States attempt to do that by calculating what the law calls the “total maximum daily load,” or TMDL, which is simply the maximum amount of a pollutant that a water body can receive and still safely meet water quality standards.

Ana Zivanovic-Nenadovic |

Under the law, states are also required to develop a plan for each impaired water body that lays out how the TMDL will be reached. However, a TMDL study and restoration plan can cost thousands of dollars and take several years to complete.

Rather than treating or removing bacteria from stormwater runoff or focusing on the sources of contamination, the method outlined in the federation’s guidebook aims to reduce the transport of bacteria by cutting the volume of stormwater runoff. If polluted stormwater runoff stays on land, the bacteria never reach coastal waters.

Coastal communities can do this by mimicking the natural surface water hydrology; or in other words, keeping stormwater on land where it does not cause a problem for water quality. Very little storm runoff drains into surface waters on a natural coastal landscape. Much of it soaks into the sandy soil instead. Depending on the type of development and soil composition, there are different methods that can be used to mimic this natural process.

“In the case of residential developments, low-impact development is the best solution,” said Zivanovic-Nenadovic.

These types of techniques are simple and cost-efficient—from redirecting a downspout from facing the driveway to facing the lawn, to installing rain barrels and cisterns that collect rainwater. (You can learn more about these methods in the federation’s Smart Yards booklet.)

The federation initially developed and implemented this method in three watershed restoration plans: White Oak River in Onslow and Carteret counties, Lockwoods Folly River in Brunswick County, and Bradley and Hewlett’s creeks in New Hanover County. These projects confirmed that one of the best ways to restore water quality was to reduce the volume of stormwater runoff. The method was further tested and refined in three other watersheds: Howe Creek in Wilmington, Williston Creek near Beaufort, and Mattamuskeet Drainage Association in Hyde County. In fact, the guidebook is an outgrowth of the EPA grants the federation received to implement the watershed restoration plans.

Rain barrels can be inexpensive ways to control stormwater at home. Photo: Rain Solutions |

The basis of the watershed restoration plan is the volume reduction goal—the number of gallons of stormwater runoff that needs to be reduced in order to restore water quality. “We look back at when the hydrologic changes started and whether they are caused by residential development, agricultural conversion or something else; and they are different for each case,” said Zivanovic-Nenadovic.

Using aerial photography and information about soils, development history and water quality, engineers can determine a quantifiable goal by creating a hydrograph, which shows the flow rate of water over time.

“This is a long-term management approach and it will take years for the water quality to be restored, just as it took years for it to be degraded. We are still working on the case studies, but some preliminary assessments of the stormwater volume reductions show that projected volume reductions will not only be achieved but also surpassed with the restoration efforts we have in one of the three case study sites,” said Zivanovic-Nenadovic.

The volume reduction goal can be used instead of a TMDL. In fact, the guidebook frequently references the nine elements of a plan required by the EPA so that the plan can serve in place of a TMDL and qualify for federal grants.

Even if a TMDL has already been completed, the guidebook can complement restoration efforts by presenting strategies to control non-point source pollution, such as runoff from driveways. Also, the guidebook can be effective for those who want to take proactive steps in maintaining water quality for water bodies that were not considered legally impaired when the Clean Water Act was established in 1975.

The guidebook is in its final revisions and will soon appear publicly on the federation’s web site. It will be presented at various conferences including the N.C. Low-Impact Development Conference in Raleigh in March.