Polluted runoff is now the largest source of water impairment along the coast, but many think that the state’s evolving regulations are working to control it.

There are 2,219,032 acres of classified shellfish waters in the state, according to the N.C. Shellfish Sanitation Section office in Morehead City. Of those, 1,777,349 are considered open to harvest, either “permanently” or conditionally. Another 441,683 acres are closed, either permanently or conditionally. That condition, essentially, is rain. Moderate rains wash enough bacteria into the water to make the shellfish unsafe to eat.

Supporter Spotlight

The N.C. Coastal Federation and other groups in 2008 sponsored an oyster roast for legislators in Raleigh to support stronger stormwater rules, |

And although the state has generally been on the drought side of the scale in recent years, there’s enough variation that section Chief Patti Fowler has trouble saying whether closures are on the rise, holding steady or decreasing.

“What we try to do now is manage,” she said. “When it’s possible to open, we open. Our goal is to keep as much open as we can, as much of the time as we can. But we have to be able to prove to the FDA (Federal Food and Drugs Administration) that what we do is effective.”

The good news to Fowler is that the shell fishermen and the public seem to understand the effects of stormwater runoff and the need for closures far better than in the past. The agency doesn’t get nearly as many angry calls when closures occur.

“That used to be fairly common,” she said. “I think the public is aware of what we do and how we do it, or at least a lot more aware than in the past.”

But are state legislators? Do they understand?

Supporter Spotlight

One good sign might be that the current conservative N.C. General Assembly rolled back environmental rules, but hasn’t really made a serious effort to change the stormwater regulations.

Tom Reeder, director of the N.C. Division of Water Resources and who championed stronger runoff rules, believes that lawmakers get it when it comes to stormwater. “I do believe they understand, especially the coastal legislators,” he said. “They know very well the importance of good water quality to the economy along the coast: tourism and fishing. When I talk to coastal legislators, they’re very in tune to what we are trying to protect.

Charles Peterson |

But Charles “Pete” Peterson, a longtime member of the state’s Environmental Management Commission before the legislature fired the commission members this year, isn’t so confident, for a variety of reasons. A researcher at UNC’s Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City, Peterson has also been on the science advisory panel for the state Coastal Resources Commission and was integrally involved in formation of the original stormwater rules and in the 2008 update. He said he agrees it might be too early to gauge the success or failure of the 2008 rules, but isn’t sure the state is even capable of doing so.

“We don’t have nearly the resources available for monitoring that we had a relatively short time ago,” he said. “During this period of declining state revenues, there have been significant cutbacks in the staff at the Division of Water Quality (now a part of Reeder’s division).”

He’s also not sure that legislators really understand the importance of stormwater management. “From what I see and hear, I’m not convinced that on environmental issues, all the factors and implications of potential policies are being discussed,” he said.

Another problem, he said, is the state’s news media don’t devote as many resources as they once did to reporting on environmental issues, including water quality. “I get my news like everyone else these days … in bits and dribbles,” he said. “From what I do get, I don’t think there’s enough discussion. But at the same time, there’s not as much information about what is or isn’t being discussed. And because of the political climate, you can’t be assured that state agency folks are able to speak as candidly as they could.”

Fowler’s shellfish sanitation office also is responsible for the safety of another key to tourism industry that Reeder cited as a major justification for effective stormwater rules: recreational swimming waters. That program is headed by J.D. Potts.

A plume of pollution from a stream of stormwater spreads off the Outer Banks. |

According to Potts, the office tests 240 swimming areas along the coast. They are divided into three “tiers.” Tier 1 sites are along the ocean, and generally are thought to be used for swimming daily during warm weather months. Tier 2 sites are mostly in the sounds and rivers near relatively populated areas and are used three or so times a week for swimming. Tier 3 sites are generally in more remote, less populated areas, where swimming is estimated to occur about four times a month or less, but which may be used intensely for such events as the swimming portions of triathlons.

The 100 most popular swimming areas, including the ocean Tier 1 sites and the Tier 2 sites, are tested at least twice a week in spring and summer, while the Tier 3 sites are sampled at least twice each month.

There are 57 sites in Dare County and 56 in Carteret. Third on the list is Brunswick County, with 39 sites. There are 16 in Onslow County.

Samplers test for enterococcus, another bacterial organism commonly found in the intestinal tracts of warm-blooded animals. High levels of enterococci are considered an indicator of the possible presence of human waste – from sewer system spills or from stormwater runoff – which can cause serious human health problems. Swimming in polluted waters can lead to a variety of gastrointestinal ailments, as well as staph infections, ear infections and skin rashes.

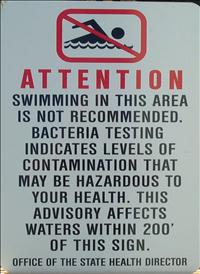

If samples show bacteria levels that exceed state safety standards, Potts and his staff post warning signs at and around the sample site and notify media. The signs stay in place until bacteria samples drop to safe levels. The state generally cannot force people to stay out of the water, but officials say most who see the signs heed the warnings.

|

Potts said that just like shellfish waters, the key to closures is rainfall and runoff. This year, he said, closures are occurring at about the same level as last year. Because of cutbacks, the office is operating this year without summer interns for the first time in years. And a bigger fear, he said, is federal funding.

North Carolina’s program began on a relatively small scale way back in 1996, but began to grow in 2000, after Congress passed a law authorizing the Environmental Protection Agency to make grants to states to help fund the effort. Since then, according to Potts, the program has received about $300,000 a year from EPA. That money pays for lab supplies and equipment, and also pays about one-fourth of Potts’s salary, plus portions of the salaries of three other staffers and the full salaries of another three.

Although the funds were threatened last year, the grant did come through. But so far, Potts said last week, the federal budget doesn’t show the grant funds. And if that were to become reality, the office might have to cut as many as half the testing sites next summer.

At any rate, while Reeder thinks North Carolina needs to stay focused on stormwater, he doesn’t think there is any need to toughen the rules.

“I don’t hear too much opposition to them any more, not like when they were first adopted, but I don’t think there is any reason to do any more right now,” he said. “It really hasn’t been that long since these went into effect. I certainly wouldn’t want to go any further until we know that what’s in place is working or not working. If it’s not working, you wouldn’t want to put new rules on top of ones that aren’t working. And if they are working, how much further do you go? I can’t see that anything more at this point is likely to be acceptable to society.”