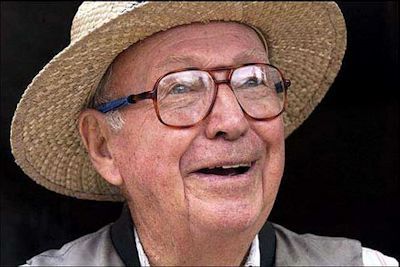

Who could refuse this face? Not many. Elmer Eddy recruited hundreds, maybe thousands, of people to join him on his crusade to pick up every last bit of trash in local waterways. Photo: AP |

Reprinted from the Tideland News

SWANSBORO — One day many years ago, when he was only 3 years old, John was in a boat with his dad on Crabtree Creek in Raleigh,

“We hit some rapids and the boat capsized,” John said Friday. “It’s one of my first memories. Somehow – they tell me I dog-paddled – I made it to this little rock. Dad got there, too, and gave me a sweater – it was December so I’m sure it was cold – and then he was gone, back down the creek to get the canoe.

Supporter Spotlight

“It was the early 1960s, so I’m sure there were no life preservers or anything like that. To dad, there was no problem. It was not anything unusual. It could easily have been a disaster, but to him it was nothing.

“I was an only child,” John continued. “My dad was my best friend. I loved him, but our relationship was always more ‘friend’ than father and son.”

With that, John choked up. Many others surely did the same Saturday, during a paddle trip down the White Oak River, because that man, that dad, was Elmer Eddy, The White Oak River Trashman, and he had died, at age 94, on July 23 in his home in Trenton.

Talk about leaving behind a legacy. Elmer Eddy had served in the Army Air Corps in Europe and had run a successful insurance agency in Raleigh in his younger days, and that’s enough for most folks.

But after following John and his family to Swansboro in 2000, Elmer began a new unpaid career and eventually left behind cleaner waters, more passable waters – from tiny creeks to wide rivers – and hundreds, if not thousands of people dedicated to following the quiet paths his oars left on many canoe trips made in those streams.

Supporter Spotlight

“He found adventure where others found adversity,” John said. “He was passionate. And he didn’t care about individual recognition, although he certainly got some along the way. What he cared about, all he really cared about was inspiring people.”

All of this, the cleaning up and the inspiring started from a small seed planted long before Elmer’s insurance career in Raleigh.

“He told me this story,” John said. “Apparently he was canoeing in a river in Providence, R.I. It was a nice, pretty river. But all of a sudden he passed through an area where there was a pipe, an open town sewer pipe. It was just raw human waste. He was disgusted. And he had an idea that maybe he could make a difference.”

That’s Elmer standing amid the trash that he and Frank Tursi of the N.C. Coastal Federation collected from Deer Creek in Bogue Sound. |

Elmer is seated next to the seven bags of trash, a tire, a chair and a mop handle that he and his trash crew picked up from Southwest Creek off the New River. The others are, from left: Dale Weston of Jacksonville, Hugh Passingham of Maplehurst, Bill Murray of Atlantic Beach, Ed Gruca of Emerald Isle and Jim Niedermeyer of Hubert. Photo: Waterway Stewards US |

Elmer, standing second from right, liked to say that if no one littered, there would be no litter. As long as they did, though. he was there picking up after them. This is the haul one day from Courthouse Bay in Onslow County. Photo: Waterway Stewards US |

But Elmer didn’t really act on that idea for a long time. He ran that insurance agency, and he enjoyed being outdoors and in his canoe, and in 1979, he went back to school. People 65 and older could go to N.C. State University tuition-free back then, and that’s what Elmer did.

He already had a bachelor’s degree in business from Northeastern University, but the outdoorsman in him led him to study horticulture.

Before too long, the Eddy home place hosted acres of plants. Grad students developed and used test plots for research.

“Dad never did anything halfway,” John said. “It was all or nothing in everything he did.”

Elmer didn’t get that degree; he got tripped up by one course that required him to memorize the common and scientific names of 250 plants. So he shifted gears, and started doing other stuff, like walking all the way around the entire perimeter of Falls Lake, which John believes was some 550 miles. He didn’t do it all at once, of course, but he did it.

When Elmer retired when John was a senior in high school, the duo boated from Key West, Fla., to Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island. That just set the stage.

“After we moved to Swansboro and he started getting into the boating here, he started seeing things he didn’t like, like trash and pollution,” John said. “He was appalled. I owned a house on the river, and had a dock, and that became his base. He started going out and bringing back trash, lots of it.”

John and Elmer, by then in his early 80s, did it alone, at first, but Elmer was a born salesman. He started posting stuff about his trash-and-paddling adventures on the computer, and, believe it or not, he started knocking on doors, cold-calling as a salesman, as it were, for help. People actually signed up.

“He found out that a lot of the trash was coming from bridges over the highways,” John said. “So he took my mother – she was in a wheel chair – and just started driving around signing people up for ‘Adopt a Highway.’ You can still see some of those signs today. He was a consummate salesman.”

That loosely bound organization became the Stewards of the White Oak River. At one point, after years of effort, John said, Elmer declared the White Oak “clean” and began expanding his efforts into the tributaries and into other rivers, including the Trent. The group became the Stewards of the White Oak River Basin, a more inclusive and expansive moniker.

Elmer and his merry band cleaned up Sugarloaf Island in Morehead City. They cleaned up Queens Creek in Swansboro, too, making friends and eating lunch with former strangers along the shore. In short, wherever there was trash in the water, Elmer was likely to be found.

They worked in rain and searing sun, they toiled and had fun in cold and in clouds of skeeters.

Elmer canoed in culverts and crevices and rapids and shallows and clearings and virtual jungles. He was like the Forrest Gump or the Eveready battery of the canoe. He just kept going and going and going …

John can’t begin to guess how much trash Elmer and his band of pickers plucked and hauled out of the creeks and rivers, but figures it had to be hundreds of tons. Eventually, he widened his focus to include not just picking up trash, but clearing branches and trees and other natural debris to make the streams navigable and more accessible to countless others.

As late as last January, Elmer and his buddies – including Leo Schmidt of Emerald Isle and Al Pace of Peletier – were heading out into those streams with a chainsaw in a 16-foot johnboat, sometimes cutting up 50-foot trees that would otherwise block the waterway.

“Talk about dangerous work,” John said. “The possible problems are endless. But they did it. And they kept on doing it. At the end, dad wasn’t able physically do a lot of the work, but he was still out there. It was his last passion.”

There were plenty of other adventures along the way, both for Elmer and John.

One time, John recalled Elmer and another close friend and “co-worker,” Gary Scruggs, decided to do some work on Pettiford Creek. They scoped the area and thought that if they went on high water, they could get the boat over the beaver dams. They got stuck.

“That night, I got a call to come and get them,” John recalled. “They didn’t have a GPS or even a flashlight, and they couldn’t find their way out.”

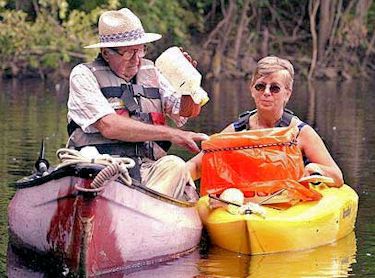

Elmer works with Joanne Somerday as they pick up trash on the White Oak River near Maysville “I want to see a beautiful wilderness,” Elmer would say. Photo: AP Elmer works with Joanne Somerday as they pick up trash on the White Oak River near Maysville “I want to see a beautiful wilderness,” Elmer would say. Photo: AP |

Elmer and Scruggs ended up spending the night in Croatan Forest in shorts and T-shirts. When John found them, he said, “they looked like hamburger,” scratched and clawed by briars and brambles and ravaged by mosquitoes.

It didn’t faze Elmer.

“I didn’t hear one negative word from him,” John said. “He was ready to go again. I think about the only thing that changed was that they got a little more careful about what time they’d start out.”

Another time, John had to emulate his dad and knock on doors to find Elmer. He and two other intrepid adventurers had gotten hung up in Starky Creek, at night. They had a GPS, so they knew about where they were, and so did John. But there wasn’t any access from any road he could find.

“I just started knocking on doors asking people how to get to the creek,” he said. “It was an interesting experience. It felt very strange. But I did it. And when I told people what he and others were doing out there, they were nice, and helpful. We finally got them out there very late that night. We went back the next day to get the canoe.”

All of this took tremendous physical stamina, and Elmer hadn’t even started doing it until his 80s. That – the mere example he set for other seniors – is another part of his legacy, and John said he knows of many who were inspired to take to the water at ages they might once have thought too advanced to do so.

Elmer’s last goal was to take his idea national, and he did so, morphing his organization into Waterway Stewards US.

John said there are many organizations and individuals he wanted to thank for helping and supporting Elmer along his amazing path, and although he knew he’d leave some out, he wanted to mention some. Elmer received a Pelican Award from the N.C. Coastal Federation, and John specifically mentioned founder Todd Miller and longtime top staffers Frank Tursi and Sally Steele. Elmer also received awards from the Onslow Clean County Committee and the coveted Green Paddle Award from the American Canoe Association.

Individuals John cited included Joanne Somerday, who organized the Twin Rivers Paddle Club’s White Oak River paddle memorial Saturday; Scott Brown, who helped drive Elmer after he gave up his driver’s license; Jim Crownover, a Pennsylvania resident and longtime friend who spent many vacation days on trash-paddle adventures; Dale Weston, a longtime friend and current head of the White Oak-New River Association; and longtime friend Kenny Metts of Jones County.

John, who does some farming in Jones County, is transitioning out of a long career as a water resources engineer.

He graduated from N.C. State and owns and operates Eddy Engineering of Raleigh and Swansboro. He’s most proud of some of his work with wetlands restoration in the Croatan Forest to mitigate DOT construction damage elsewhere, but is easing out of the field.

He said he plans to keep the Waterway Stewards US alive, and maybe even enhance it a bit. He might shift the focus a little more toward water quality – his own passion – and said he wants the far-flung network of stewards and friends of stewards to feel comfortable there and keep coming back.

It’s a great place to read about rivers and streams, and see some amazing pictures and take in tales of adventurers.

“You can also hear my dad explain much in his own words in the ‘Purposeful Paddlers’ video linked on the right sidebar,” John said. “In fact, one of best things about the site – part of dad’s legacy – is that it’s just a great source of information about the rivers and creeks.”

Posts to the website are archived all the way back to January 2001.

John said that although Elmer never actively solicited donations for the work he and the others did, he did accept donations to the Waterway Stewards US in lieu of flowers after Elmer’s death, and will continue to do so.